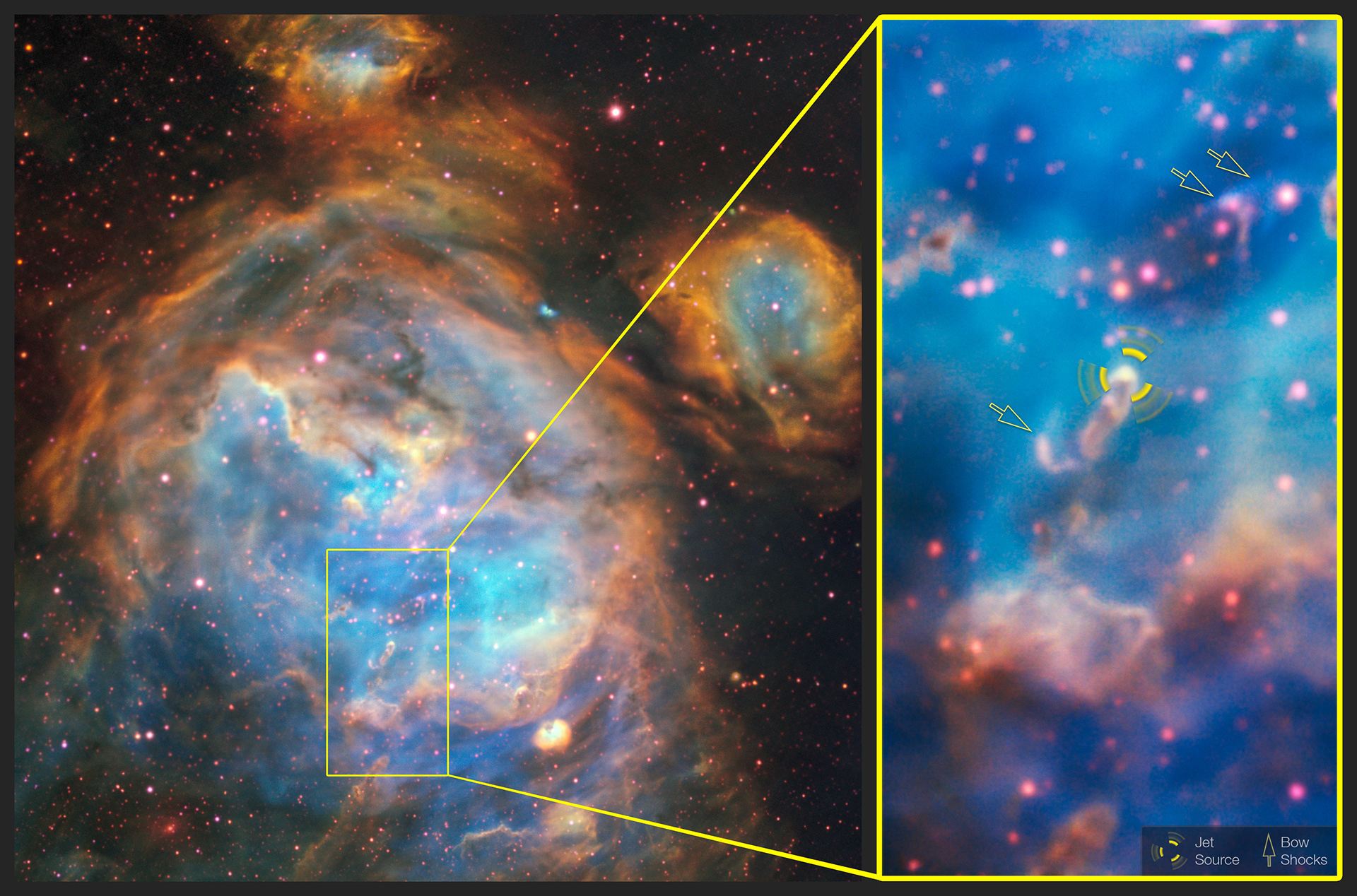

NGC 602 (NIRCam and MIRI image)- Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, P. Zeidler, E. Sabbi, A. Nota, M. Zamani (ESA/Webb)

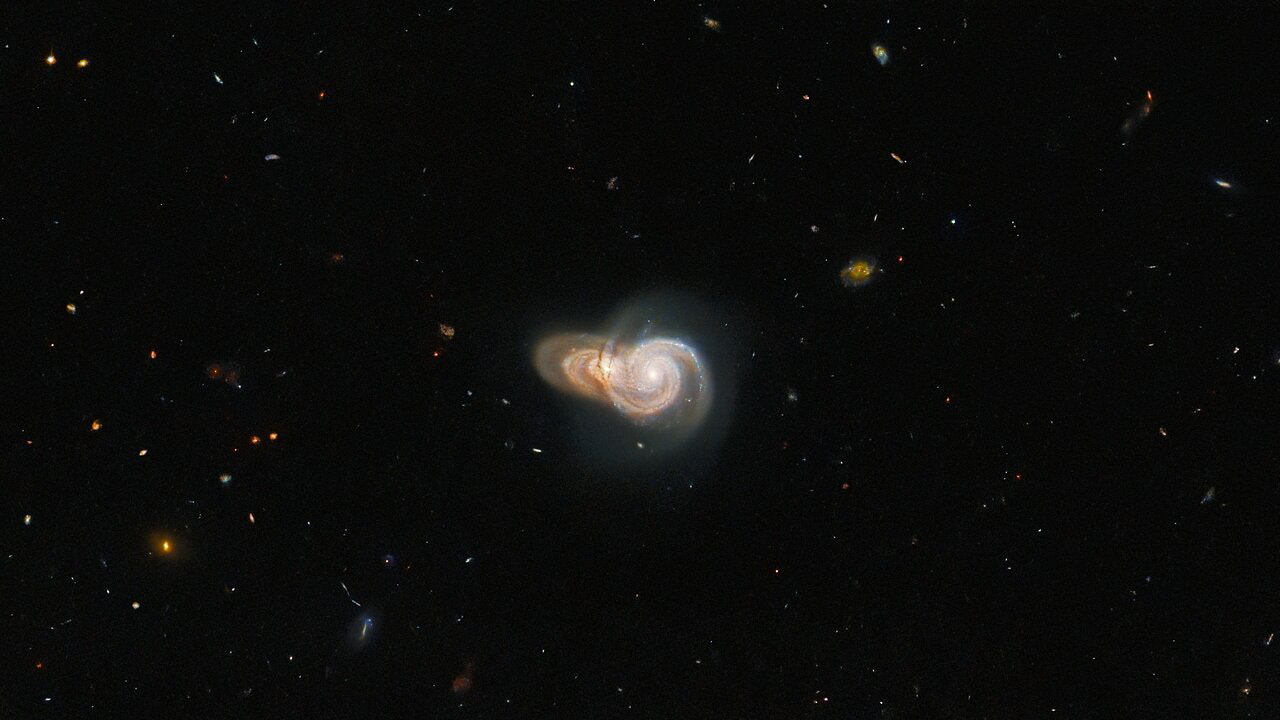

Image of the interacting galaxy pair NGC 5394/5 obtained with NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory’s Gemini North 8-meter telescope on Hawai’i’s Maunakea using the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph in imaging mode. This four-color composite image has a total exposure time of 42 minutes. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

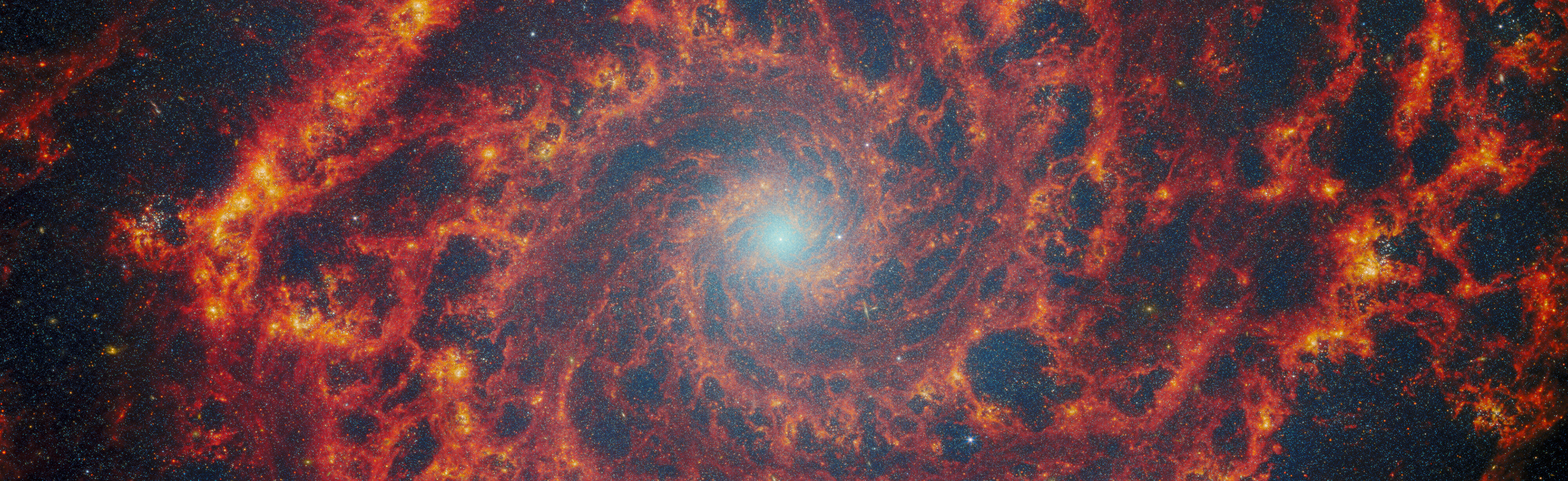

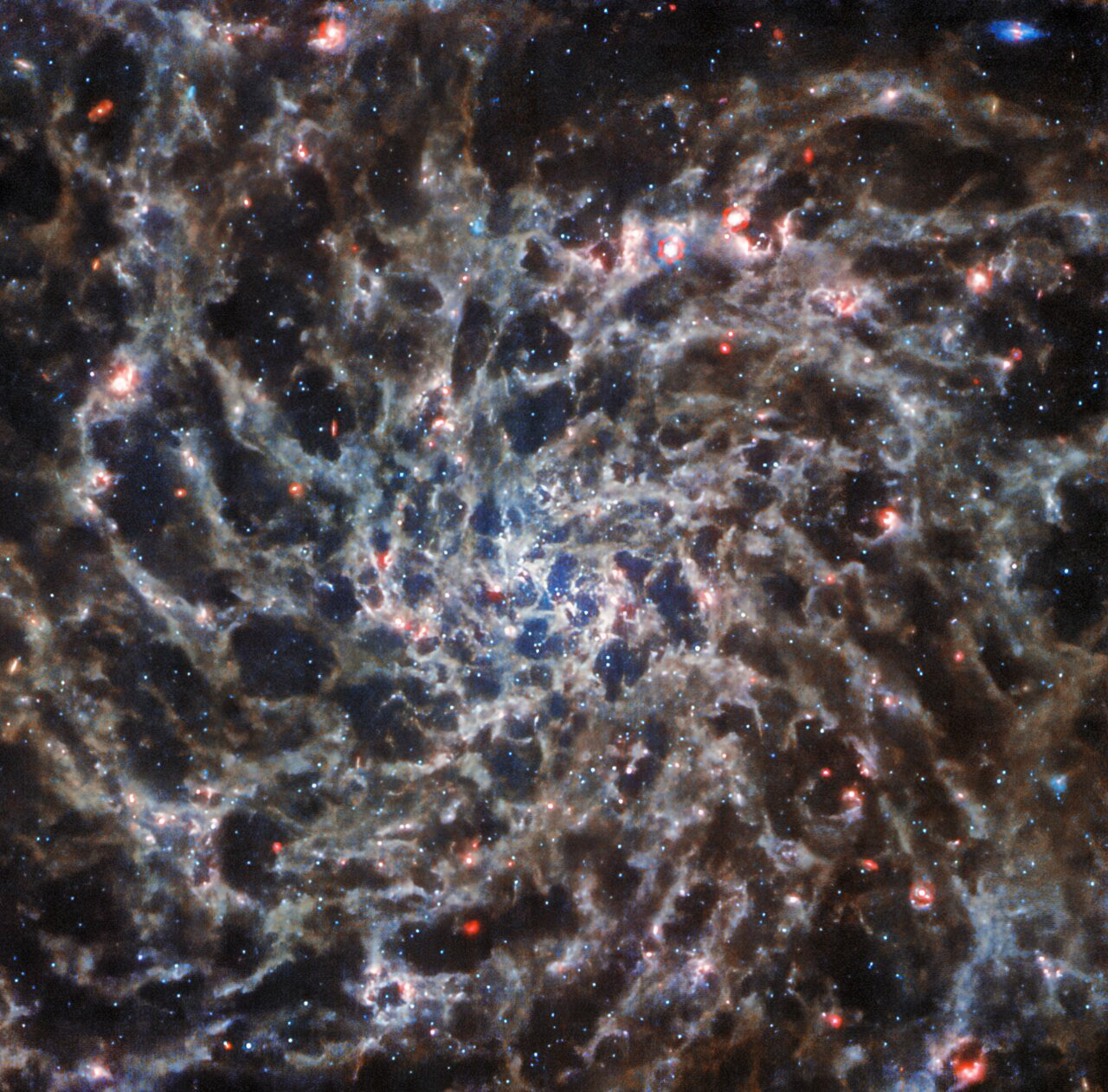

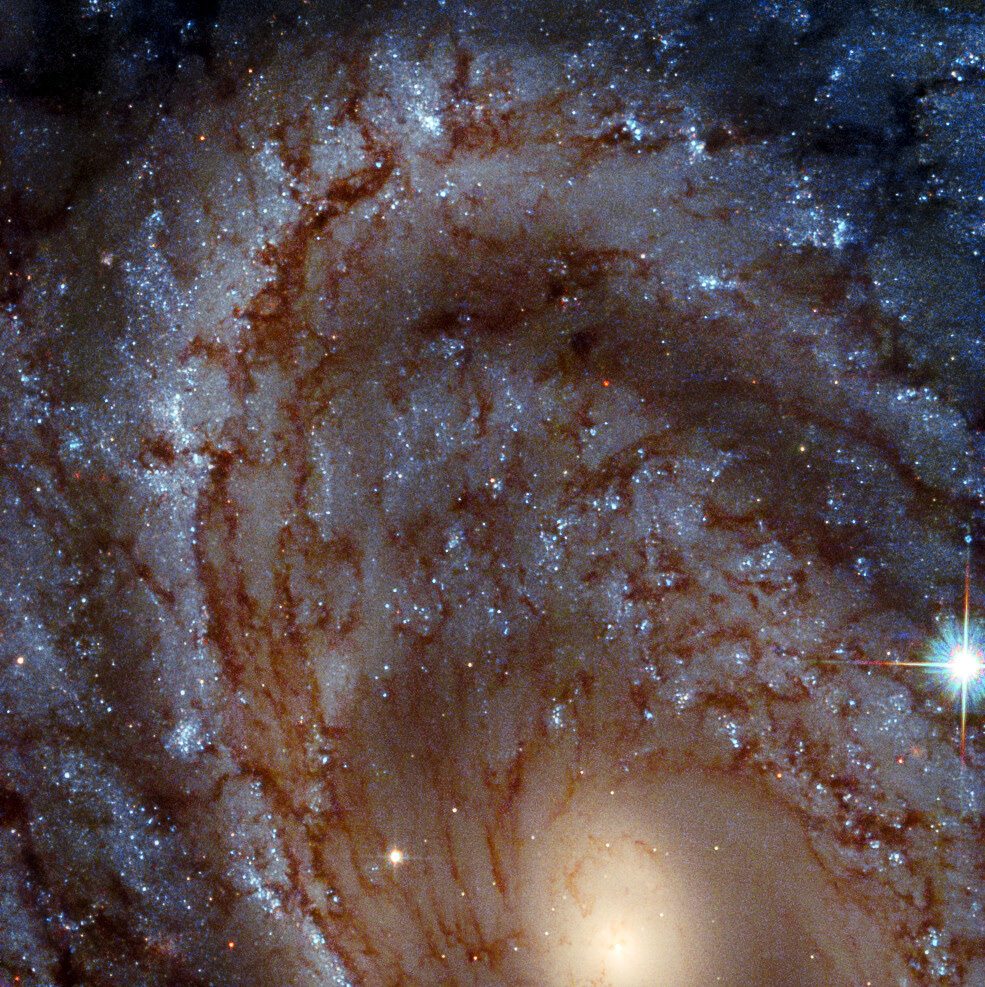

M51 (MIRI image) - Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, A. Adamo (Stockholm University) and the FEAST JWST team

Horsehead Nebula (NIRCam image) - Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, K. Misselt (University of Arizona) and A. Abergel (IAS/University Paris-Saclay, CNRS)

Peeking into Perseus (wide field view) - Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, A. Scholz, K. Muzic, A. Langeveld, R. Jayawardhana

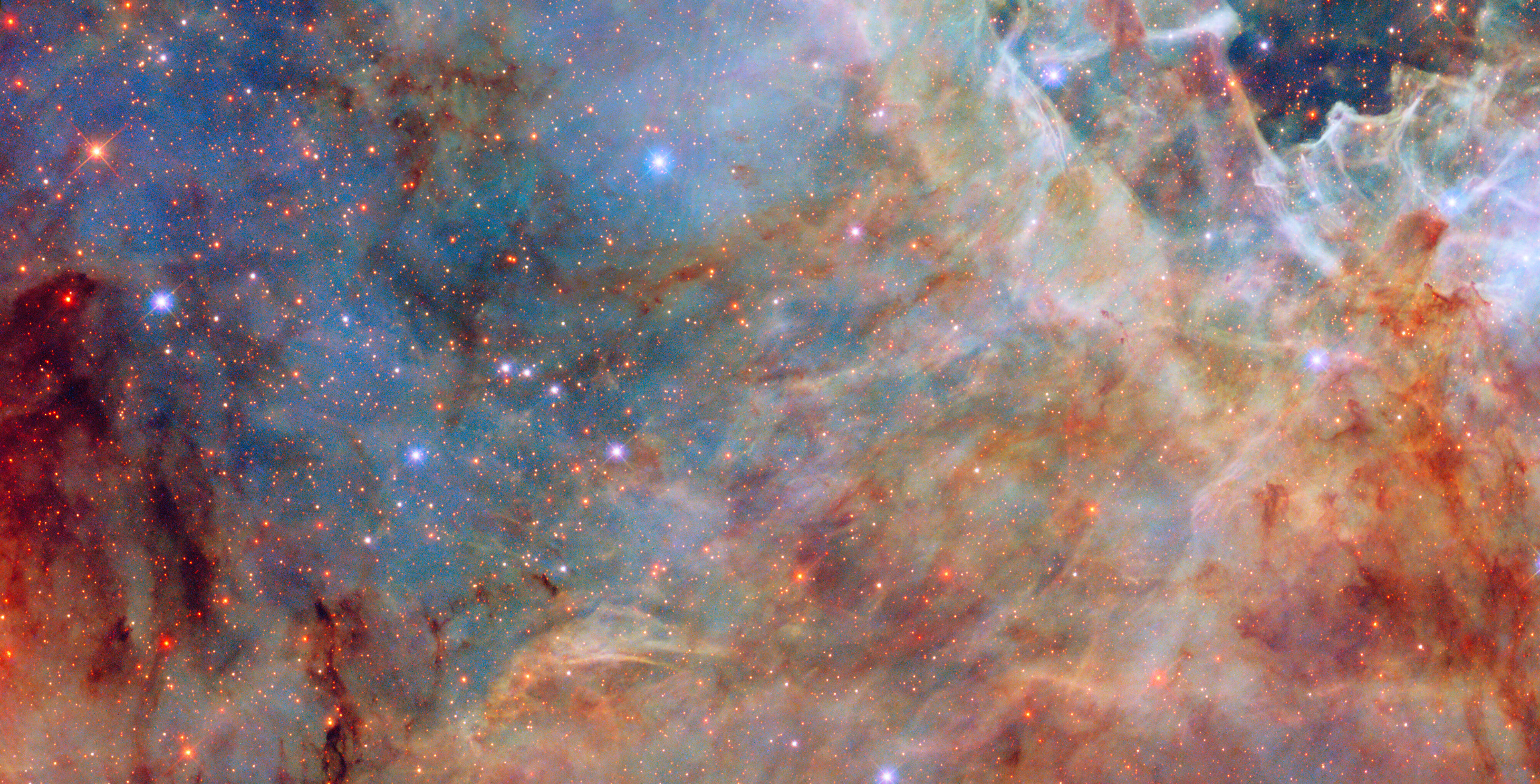

Stellar sculptors in NGC 346 - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Nota, P. Massey, E. Sabbi, C. Murray, M. Zamani (ESA/Hubble)

Spying a spiral through a cosmic lens - Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, G. Mahler Acknowledgement: M. A. McDonald

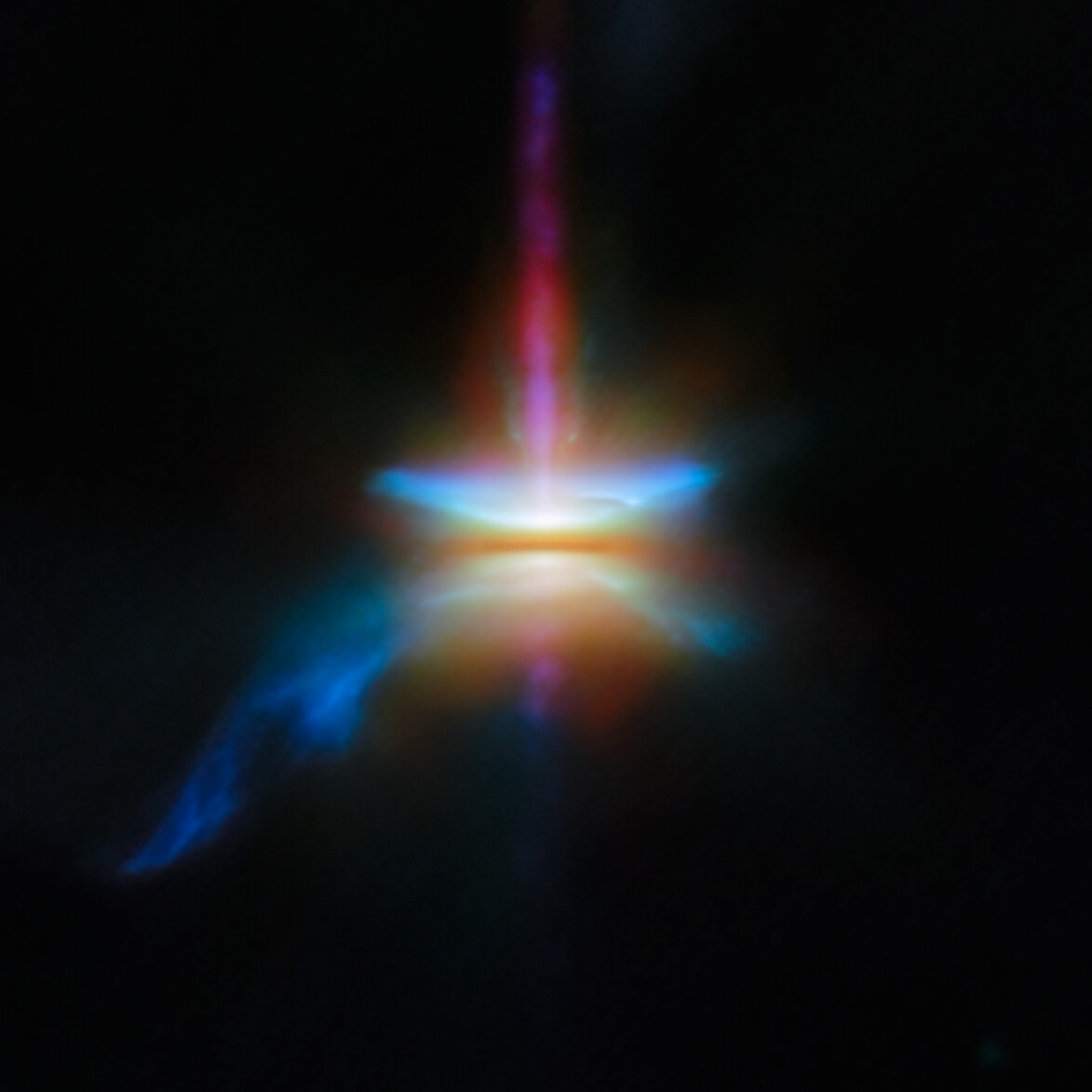

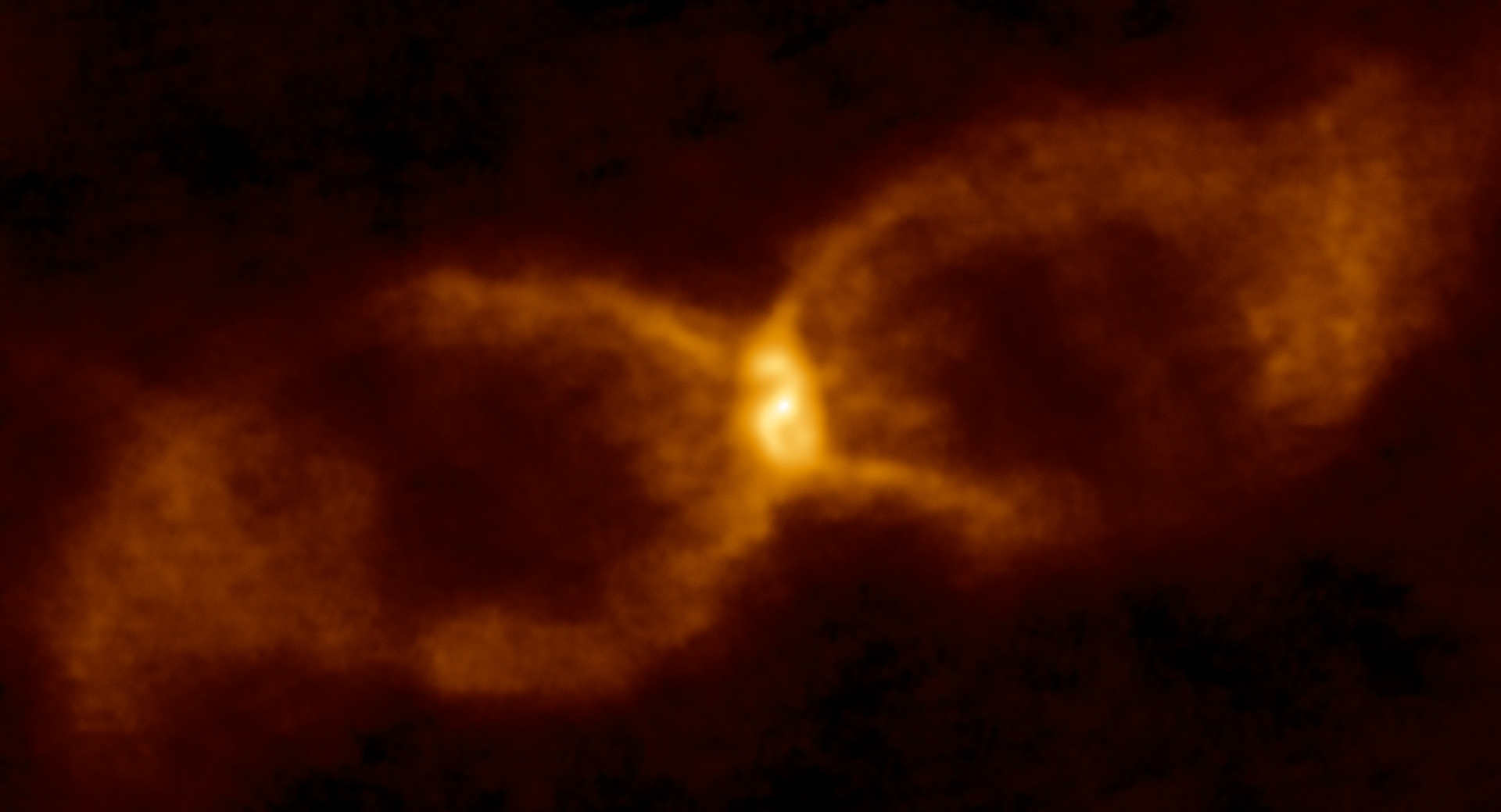

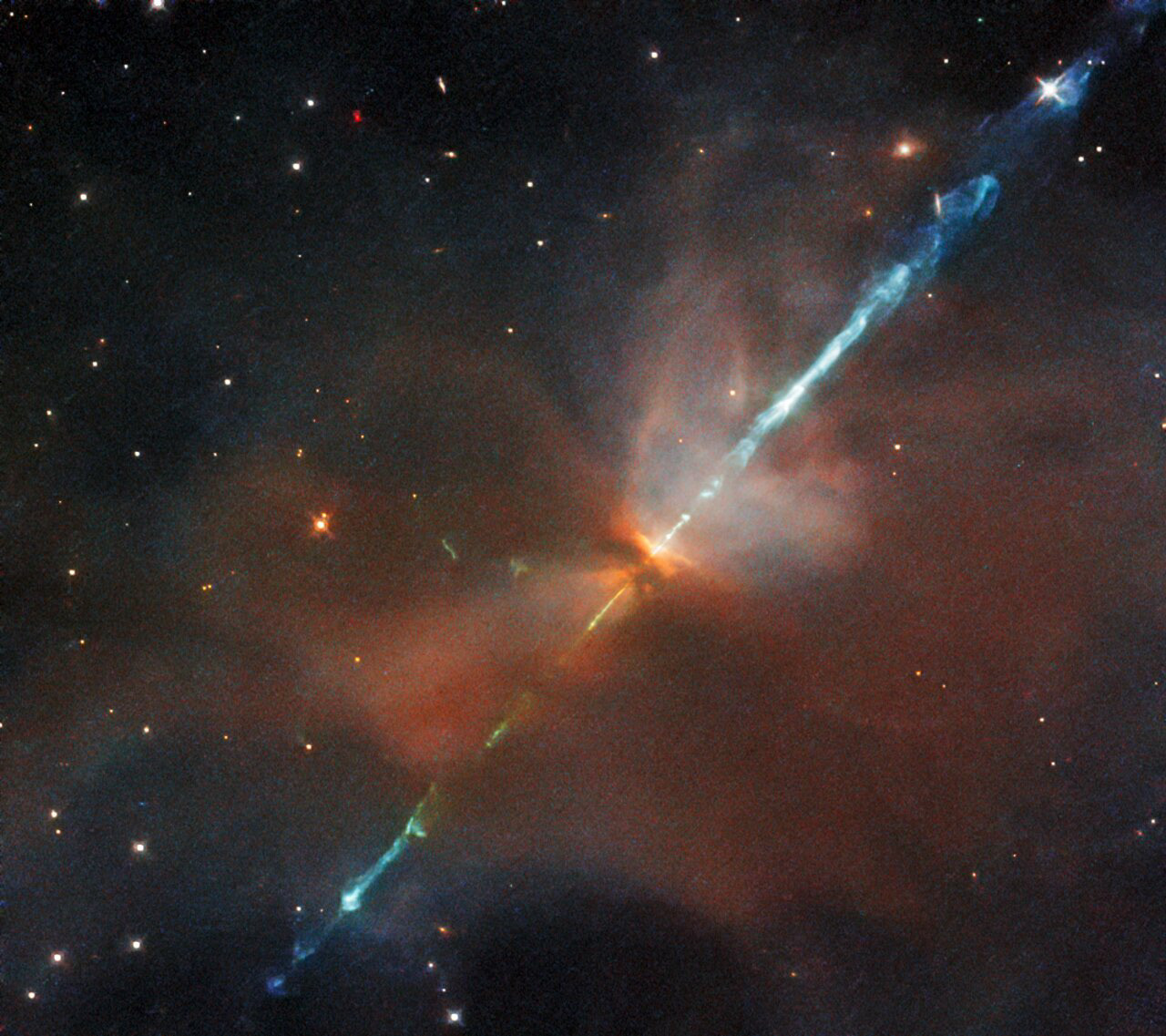

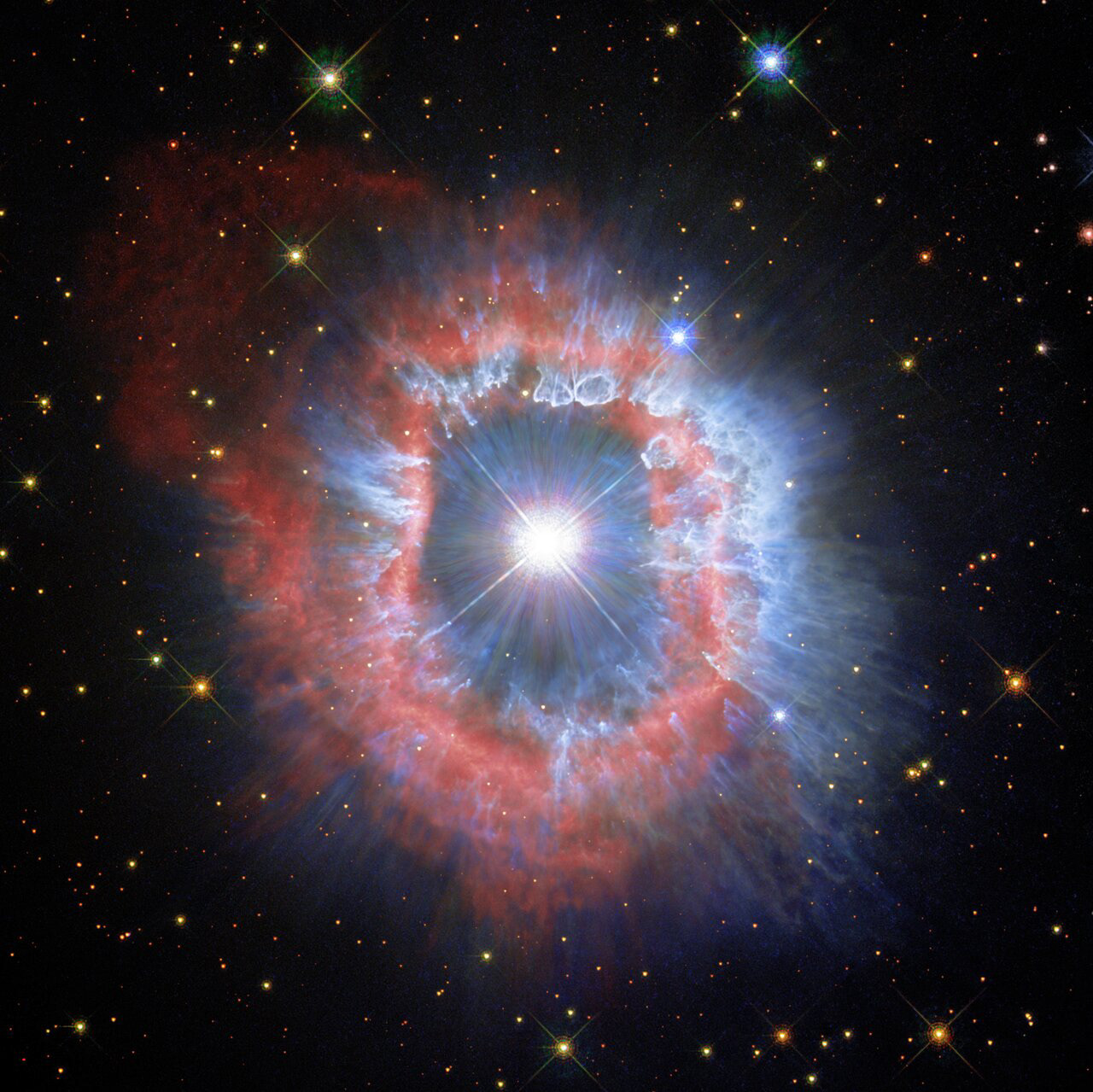

R Aquarii - Credit: NASA, ESA, M. Stute, M. Karovska, D. de Martin & M. Zamani (ESA/Hubble)

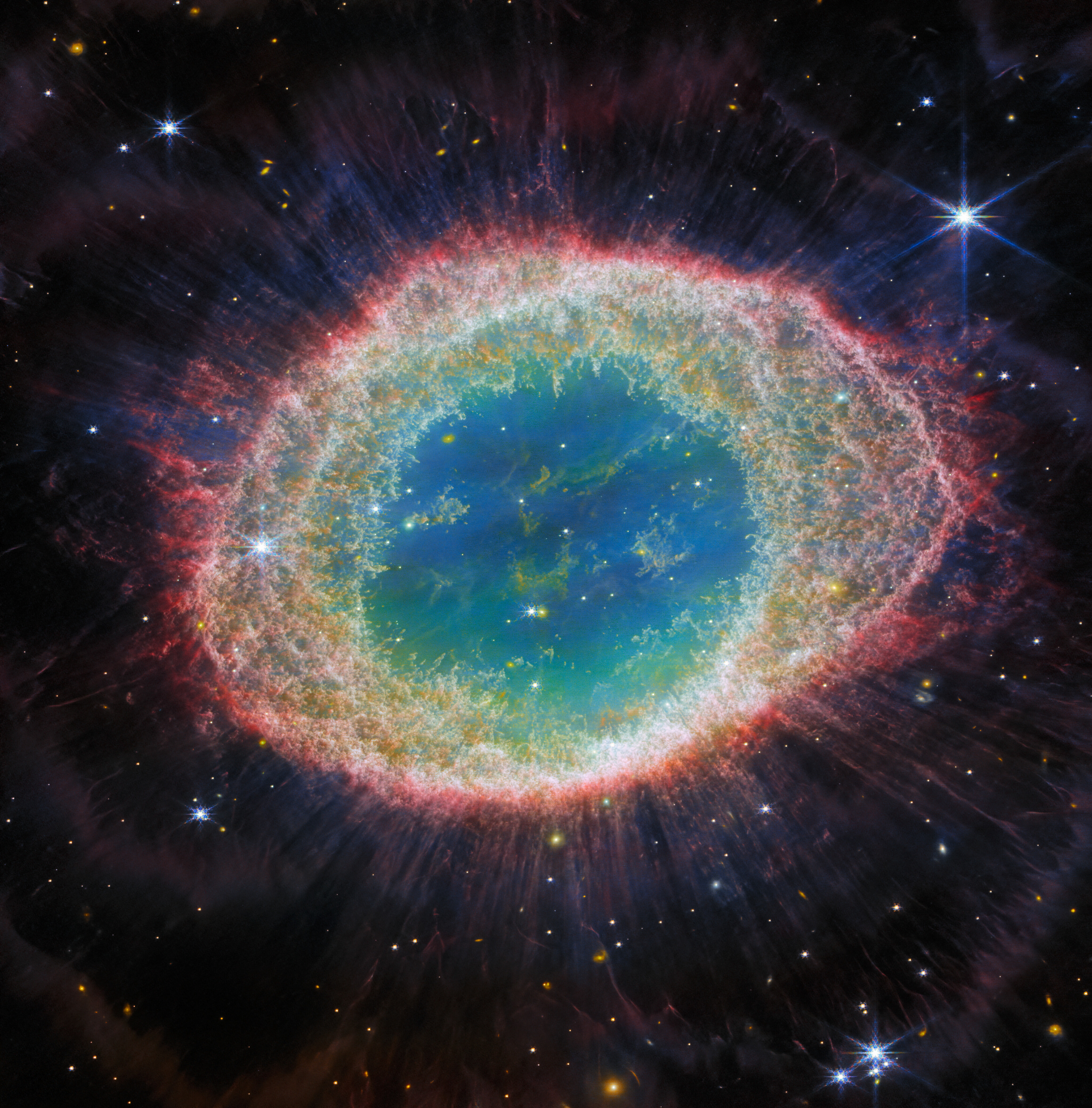

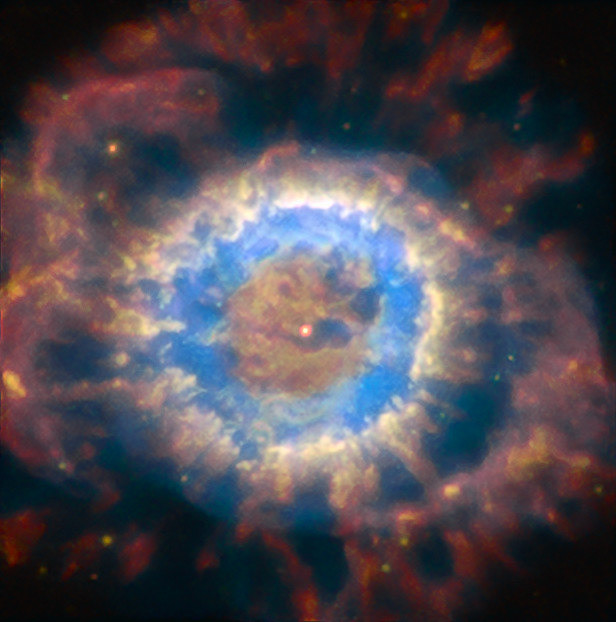

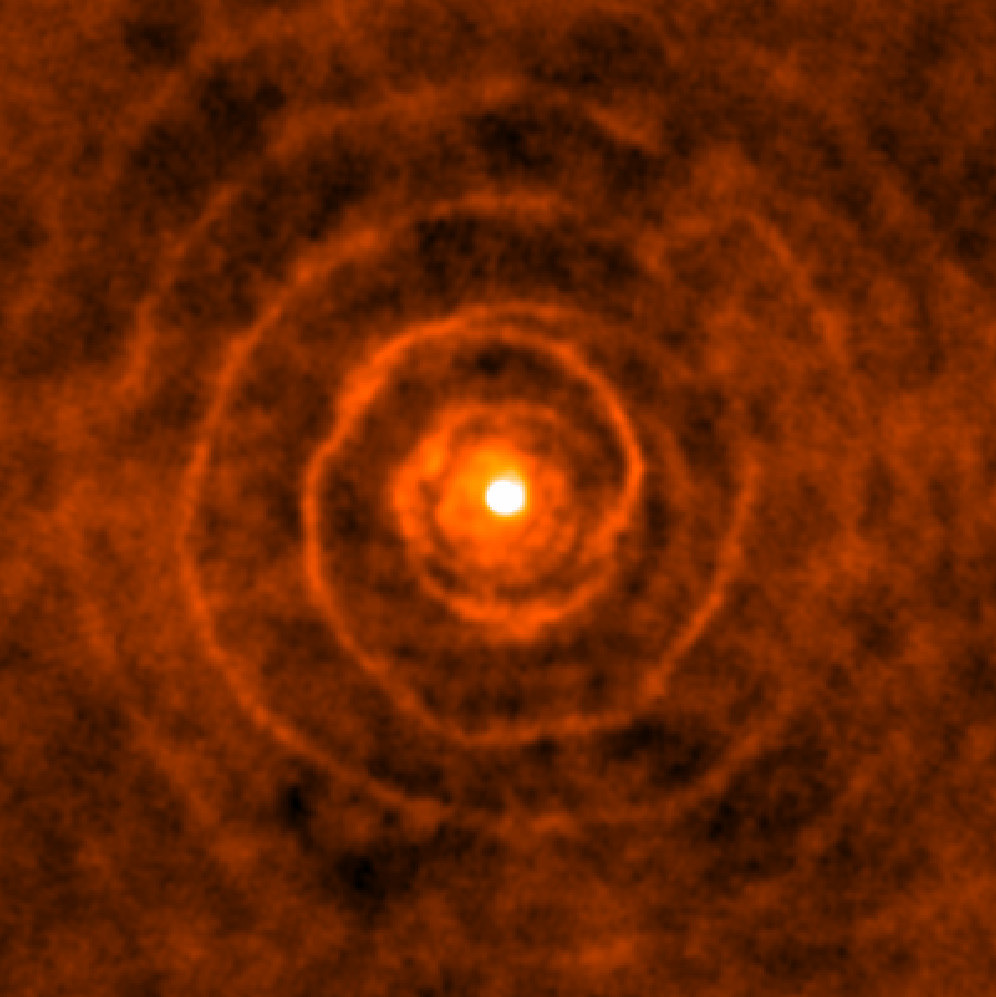

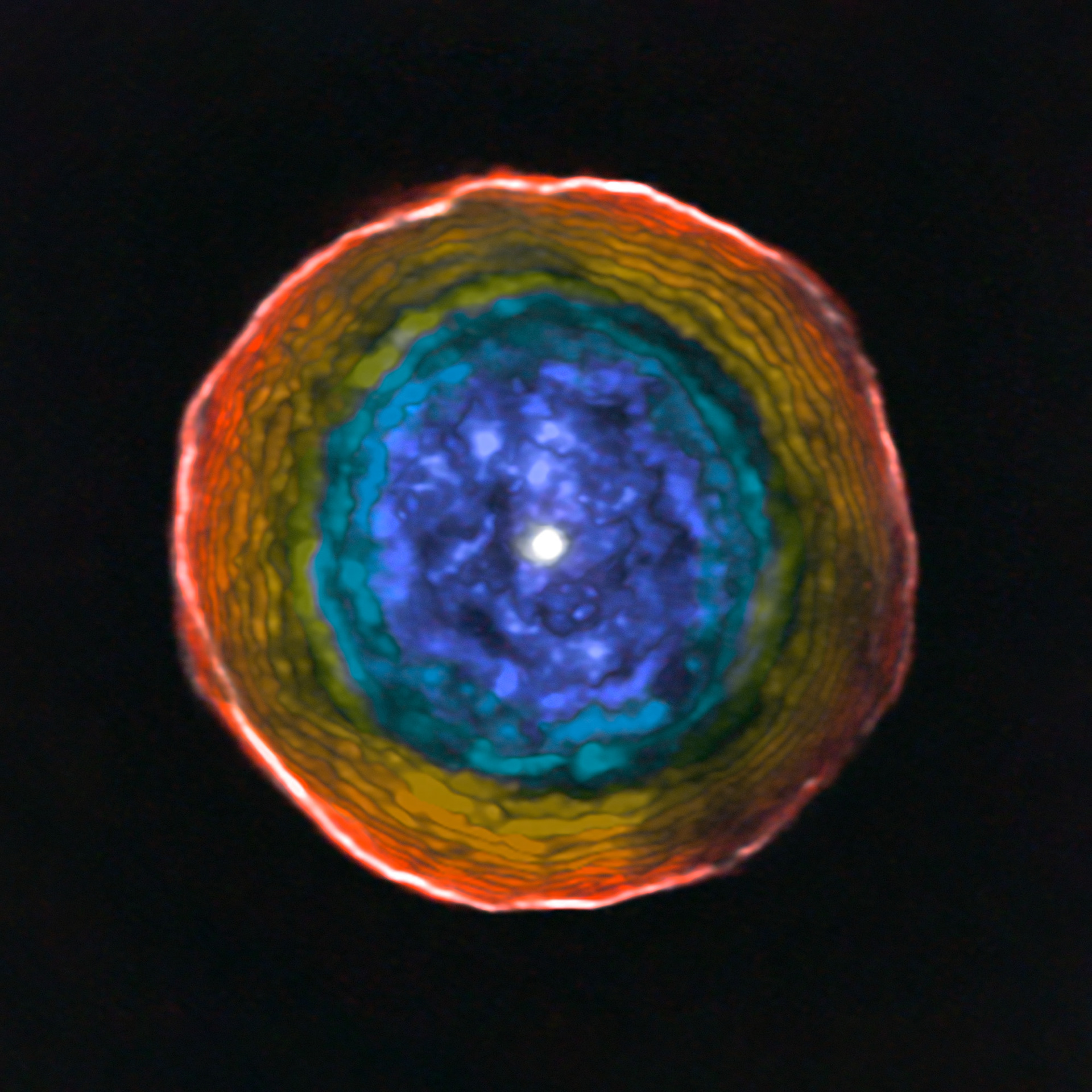

Webb captures detailed beauty of Ring Nebula (NIRCam image) Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, M. Barlow, N. Cox, R. Wesson

Westerlund 1 (wide-field view) - Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, M. Zamani (ESA/Webb), M. G. Guarcello (INAF-OAPA) and the EWOCS team

Sombrero Galaxy (Hubble35 version) - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, K. Noll

This Picture of the Week revisits the Veil Nebula, a popular subject for Hubble images! This object was featured in a previous Hubble photo release, but now new processing techniques have been applied, bringing out fine details of the nebula’s delicate threads and filaments of ionised gas. To create this colourful image, observations taken by Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 instrument through 5 different filters were used. The new post-processing methods have further enhanced details of emissions from doubly ionised oxygen (seen here in blues), ionised hydrogen and ionised nitrogen (seen here in reds). The Veil Nebula lies around 2100 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Cygnus (The Swan), making it a relatively close neighbour in astronomical terms. Only a small portion of the nebula was captured in this image. The Veil Nebula is the visible portion of the nearby Cygnus Loop, a supernova remnant formed roughly 10 000 years ago by the death of a massive star. The Veil Nebula’s progenitor star — which was 20 times the mass of the Sun — lived fast and died young, ending its life in a cataclysmic release of energy. Despite this stellar violence, the shockwaves and debris from the supernova sculpted the Veil Nebula’s delicate tracery of ionised gas — creating a scene of surprising astronomical beauty. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, Z. Levay

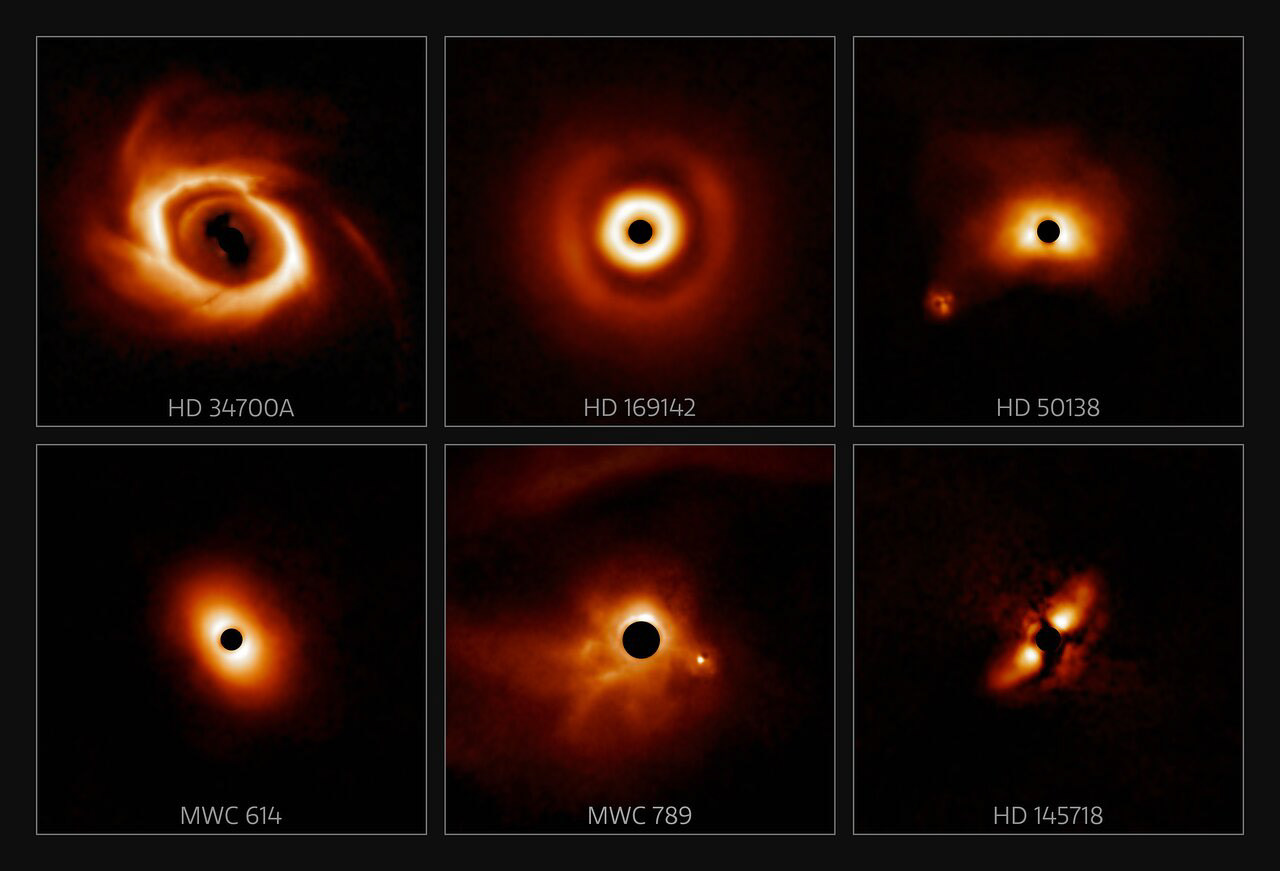

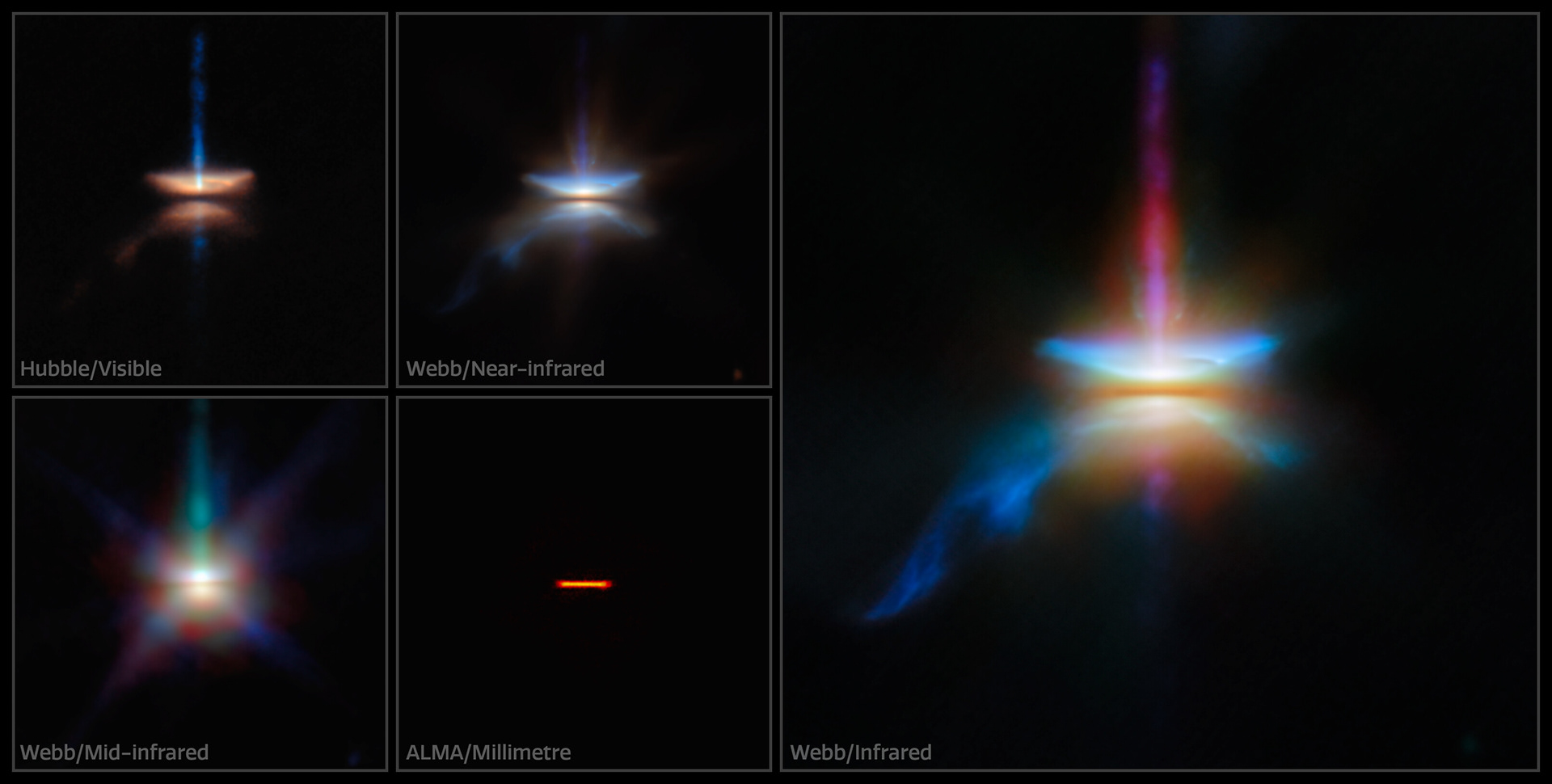

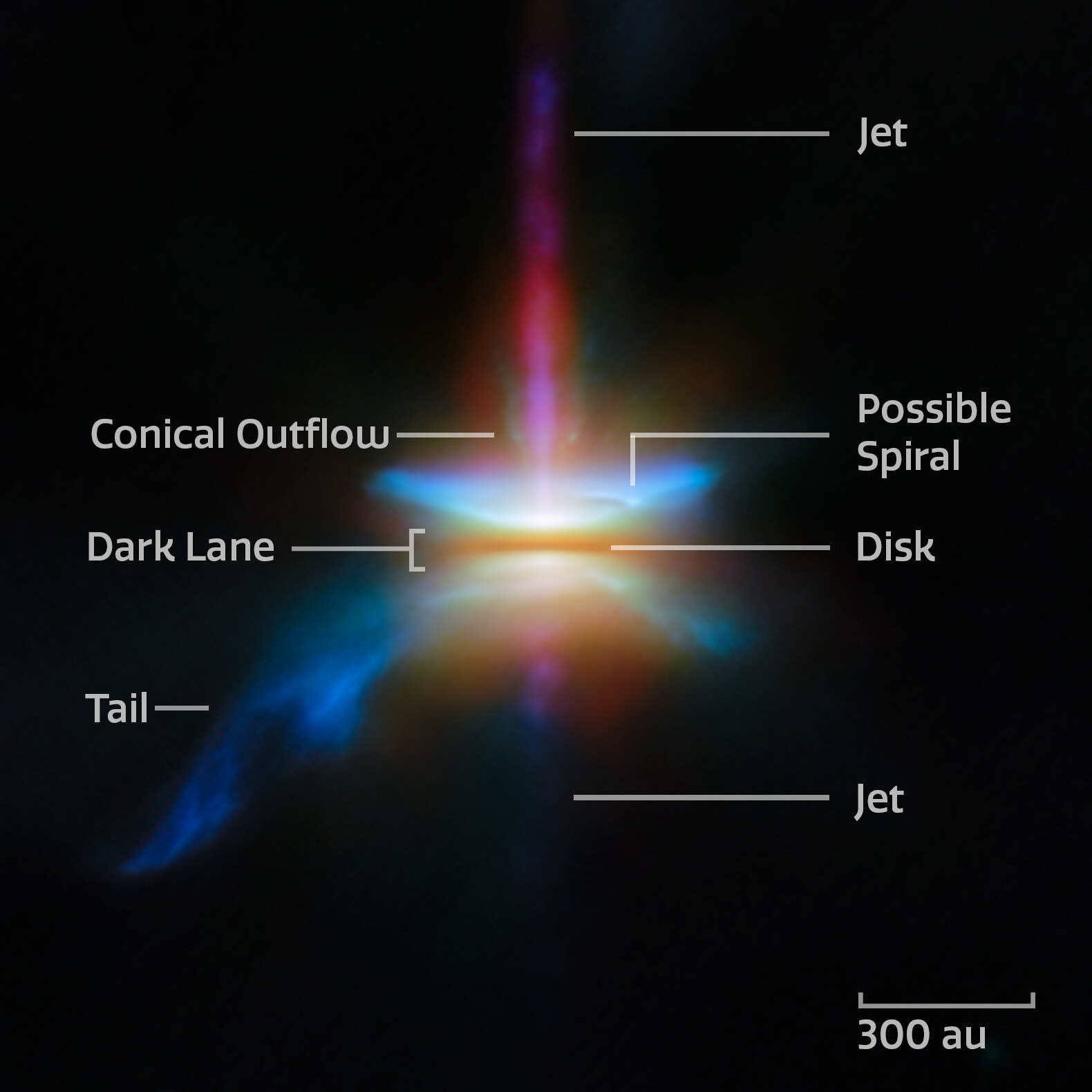

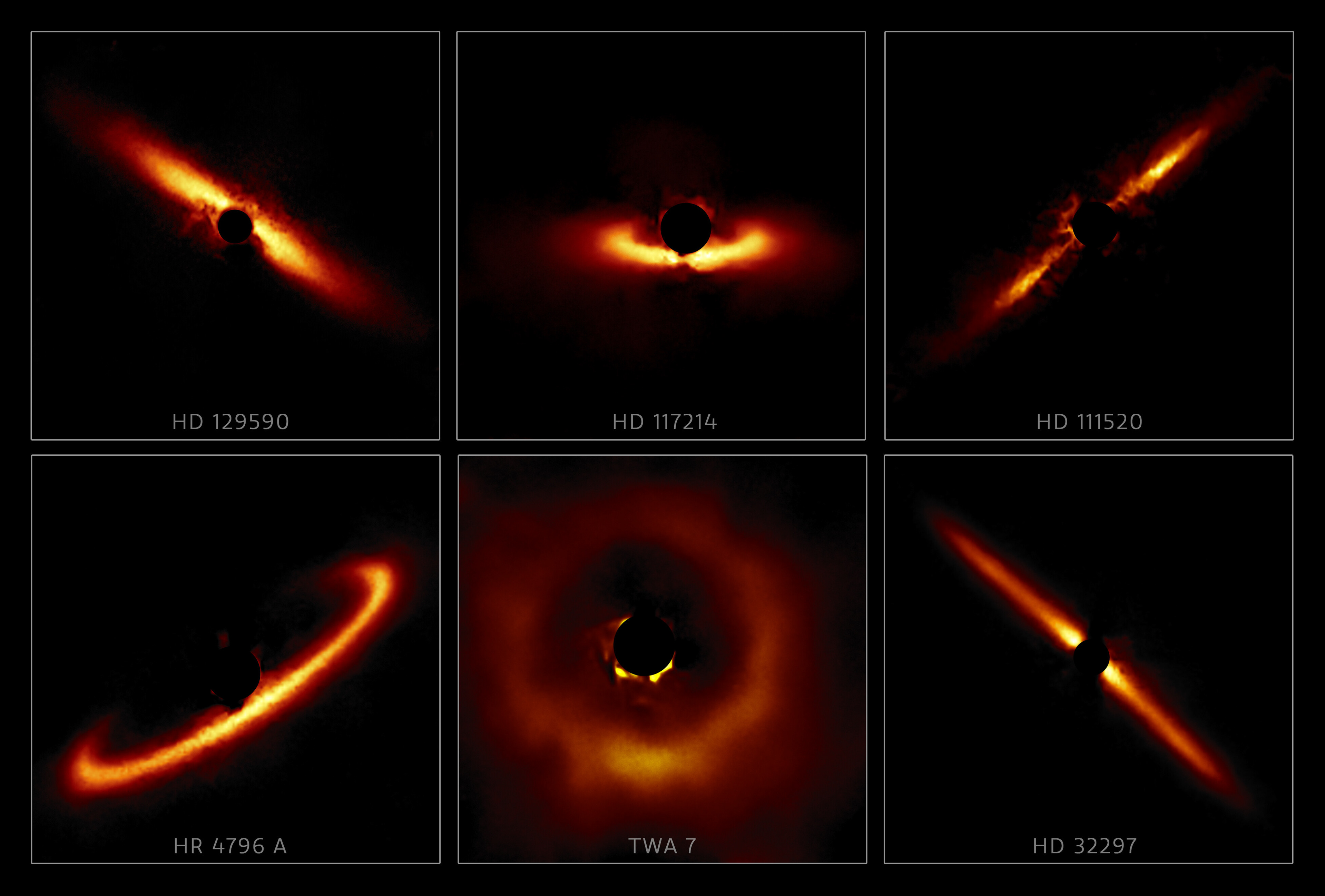

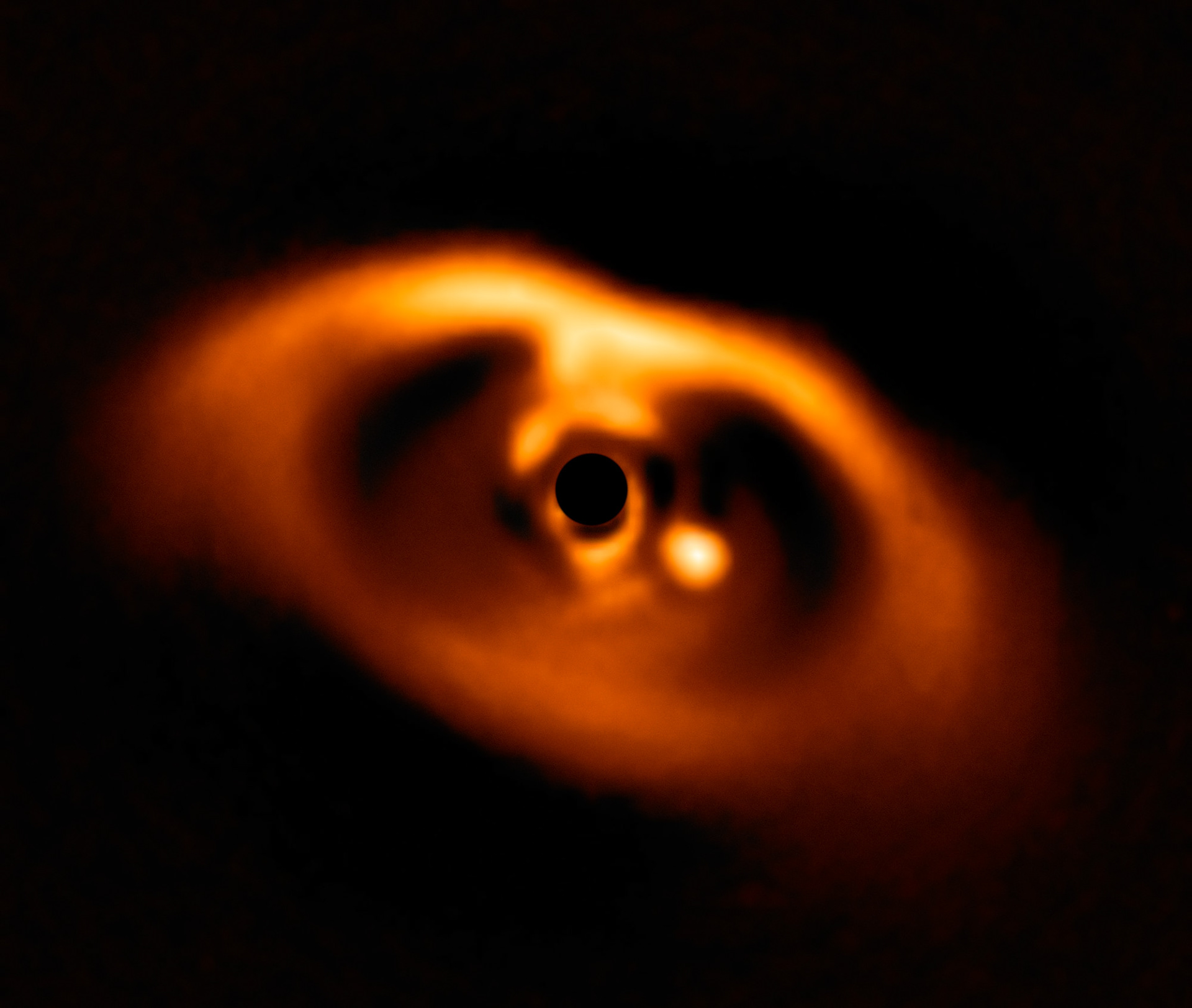

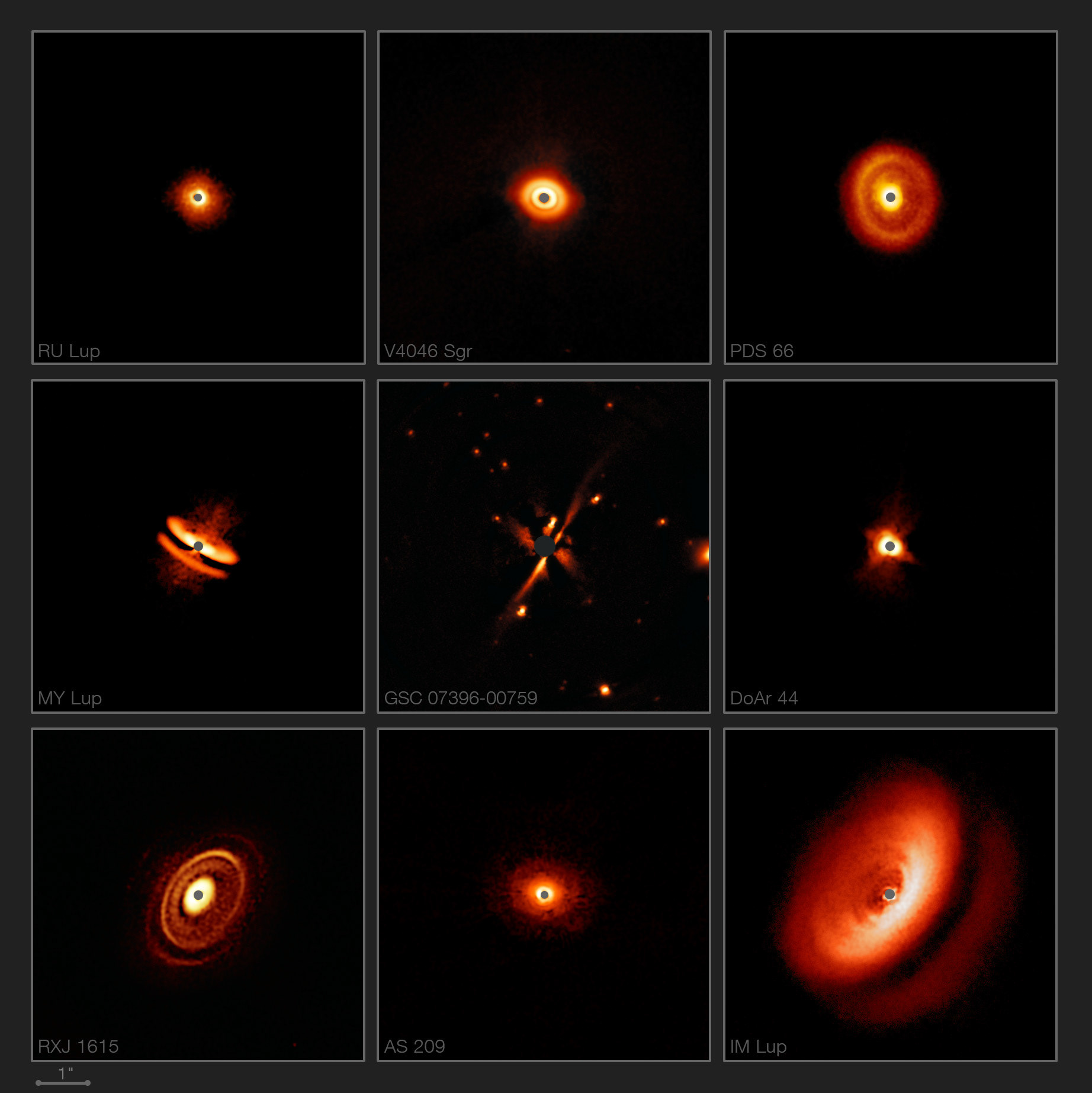

Webb spies a multifaceted disc - Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, Tazaki et al.

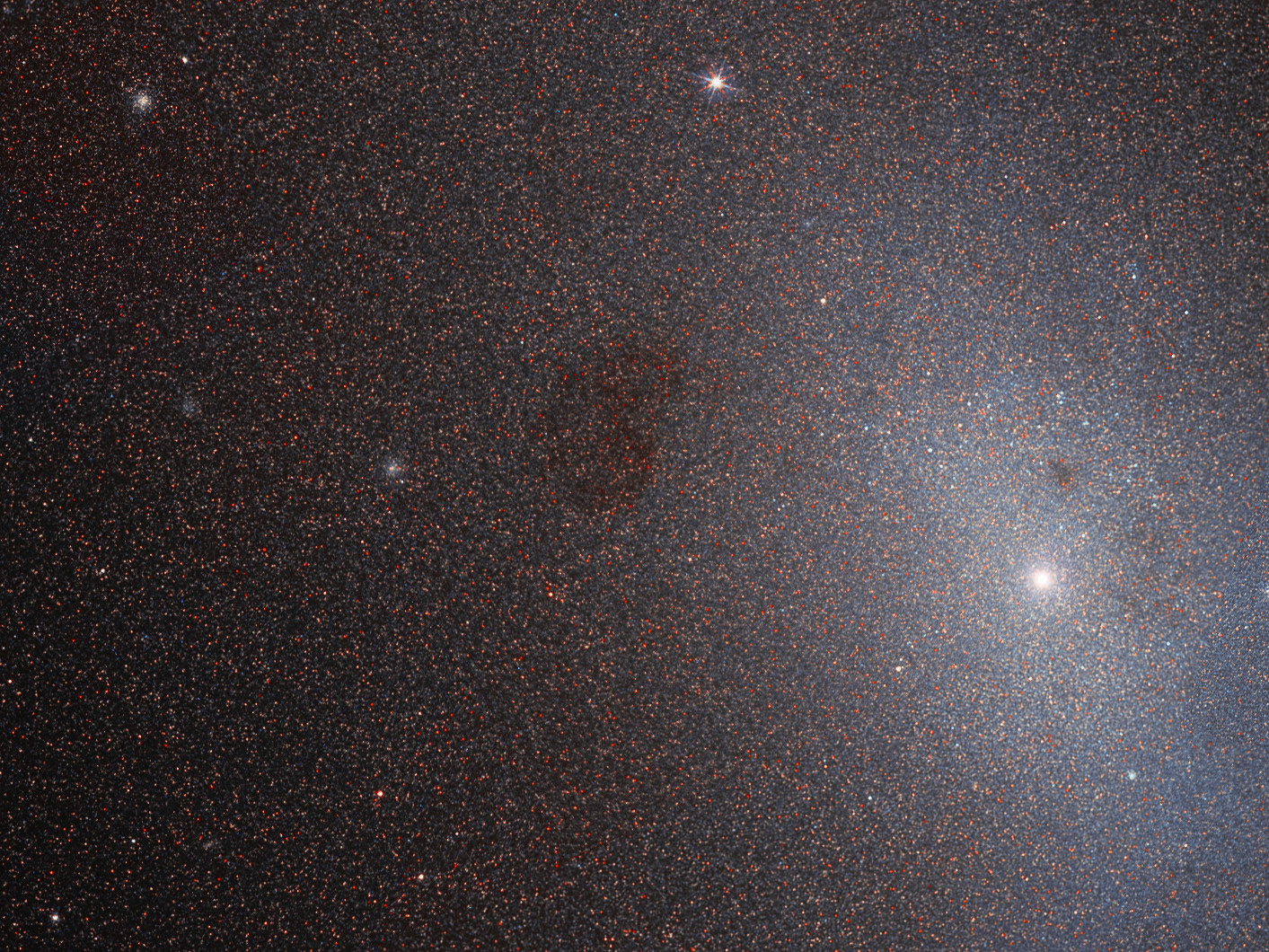

Omega Centauri - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, M. Häberle (MPIA)

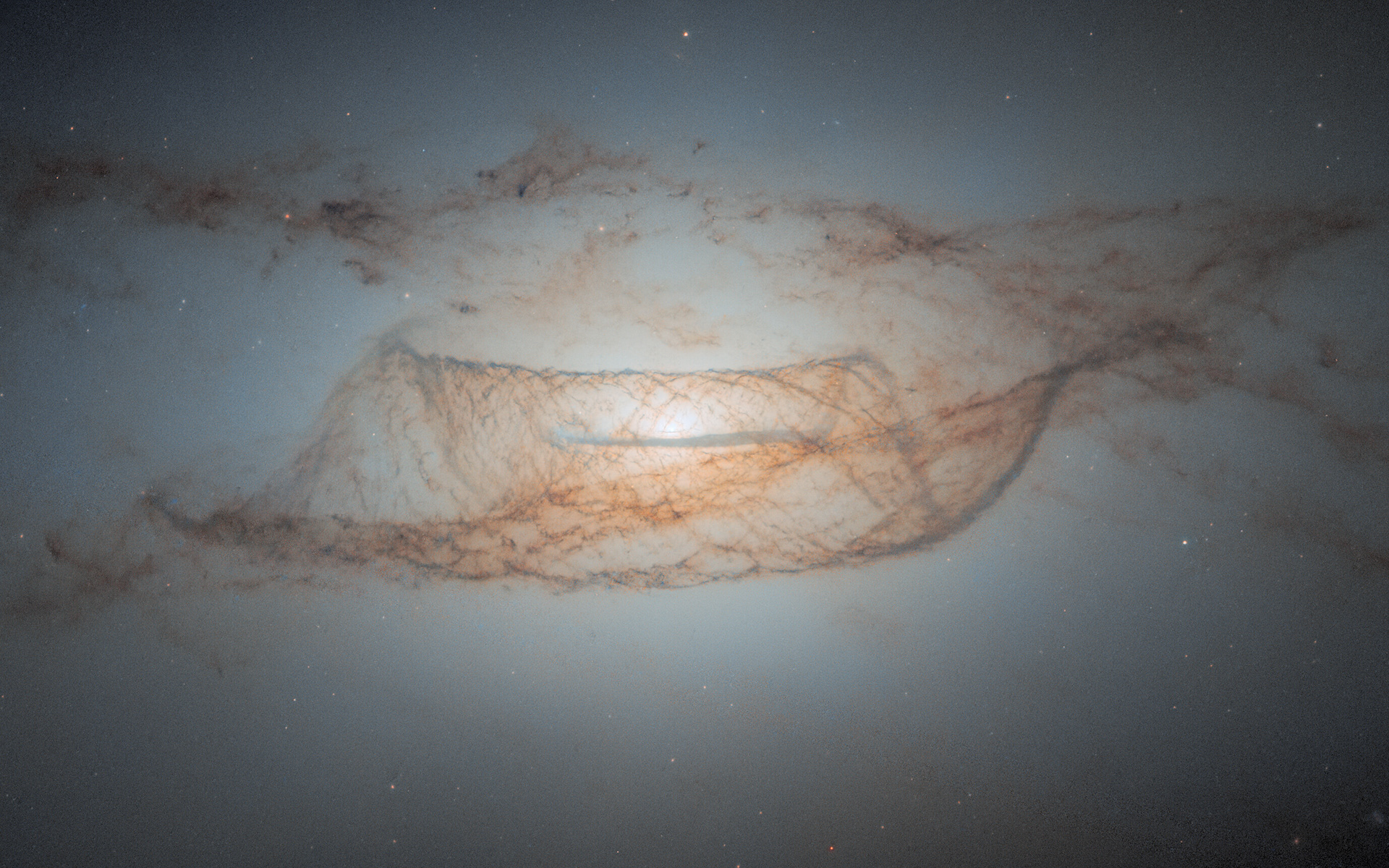

Lenticular dust in detail - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, L. Kelsey

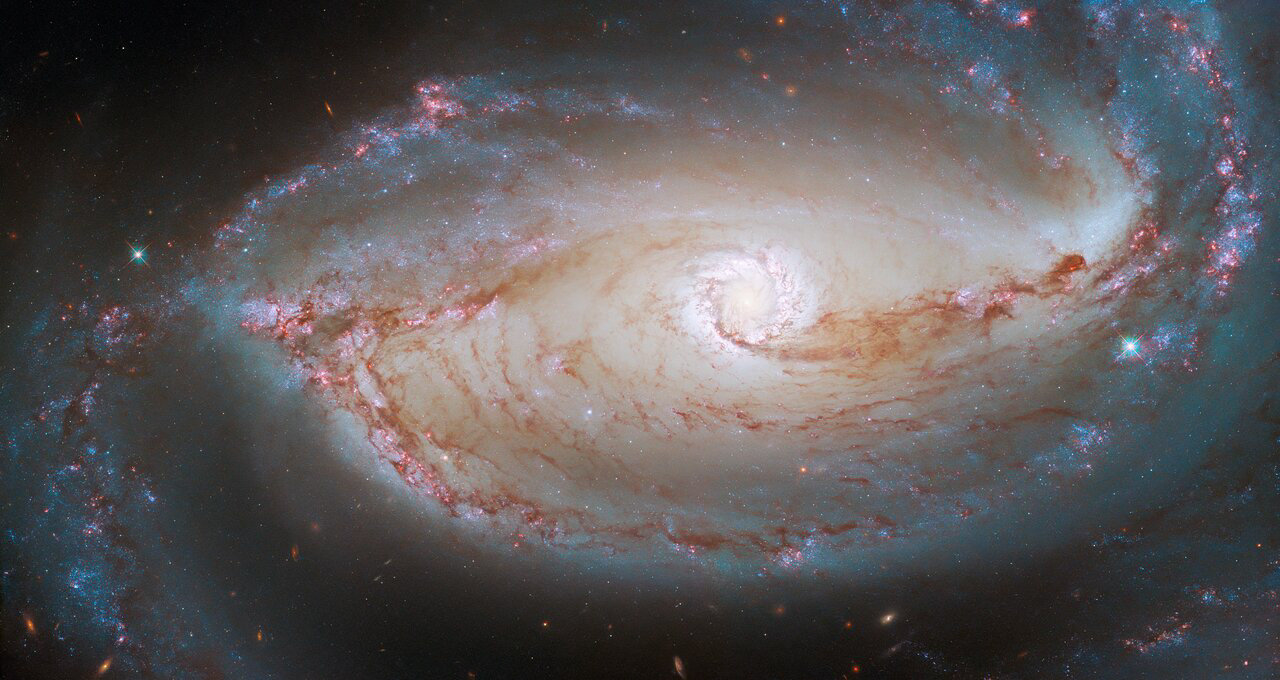

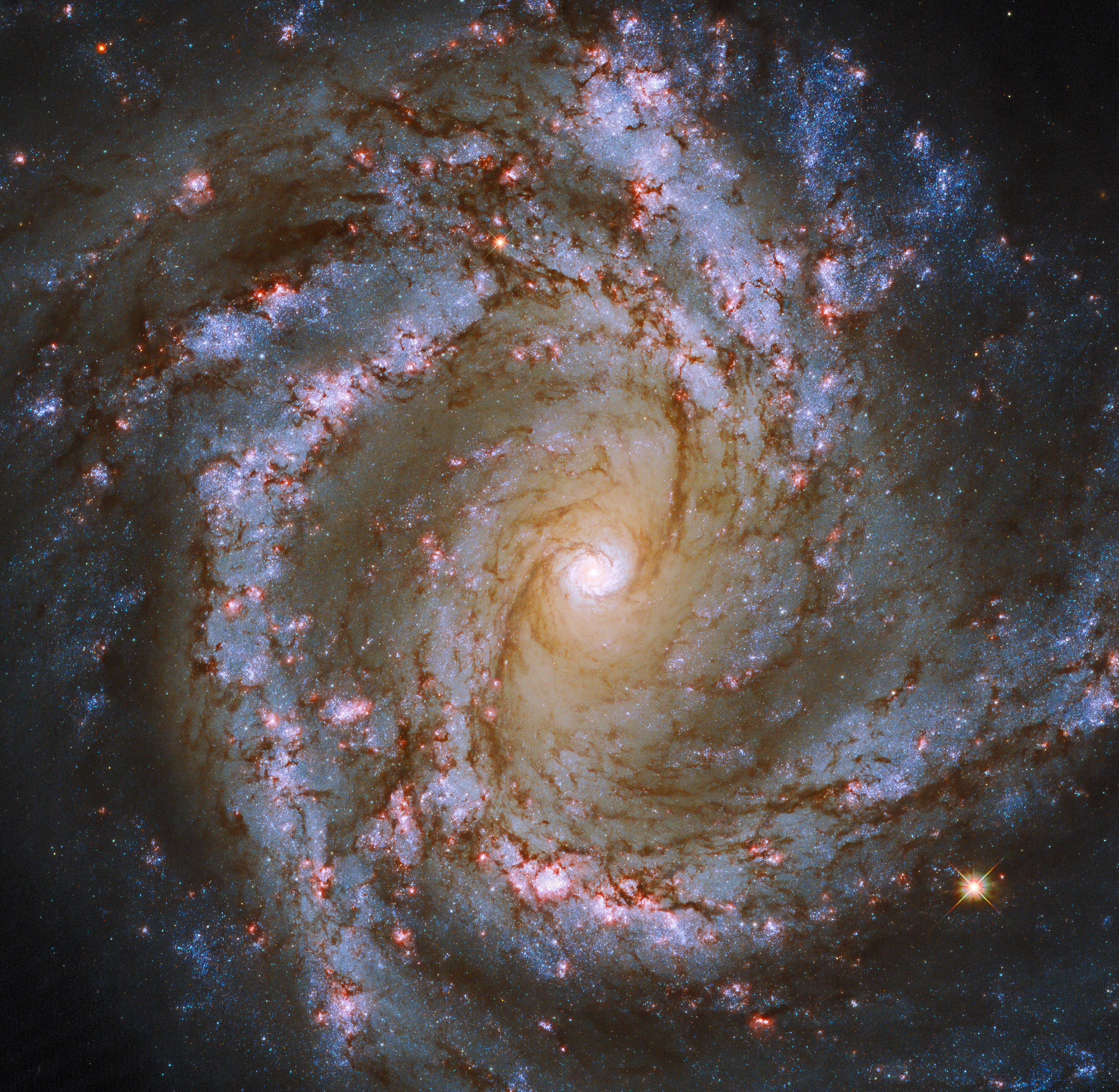

Nicknamed the Southern Pinwheel, Messier 83 (or NGC 5236) is a stunning face-on spiral galaxy located about 15 million light-years away in the southern constellation of Hydra. Its spiral arms are lined with dark lanes of dust and peppered with reddish, star-forming clouds of hydrogen gas. One of the deepest images ever taken of the Southern Pinwheel (combining more than 11 hours of exposure time), this view was captured with the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), which was built by the US Department of Energy (DOE) and is mounted on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Numerous background galaxies, which lie much farther away than Messier 83, appear around the edges of the image. Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Acknowledgment: M. Soraisam (University of Illinois) Image processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

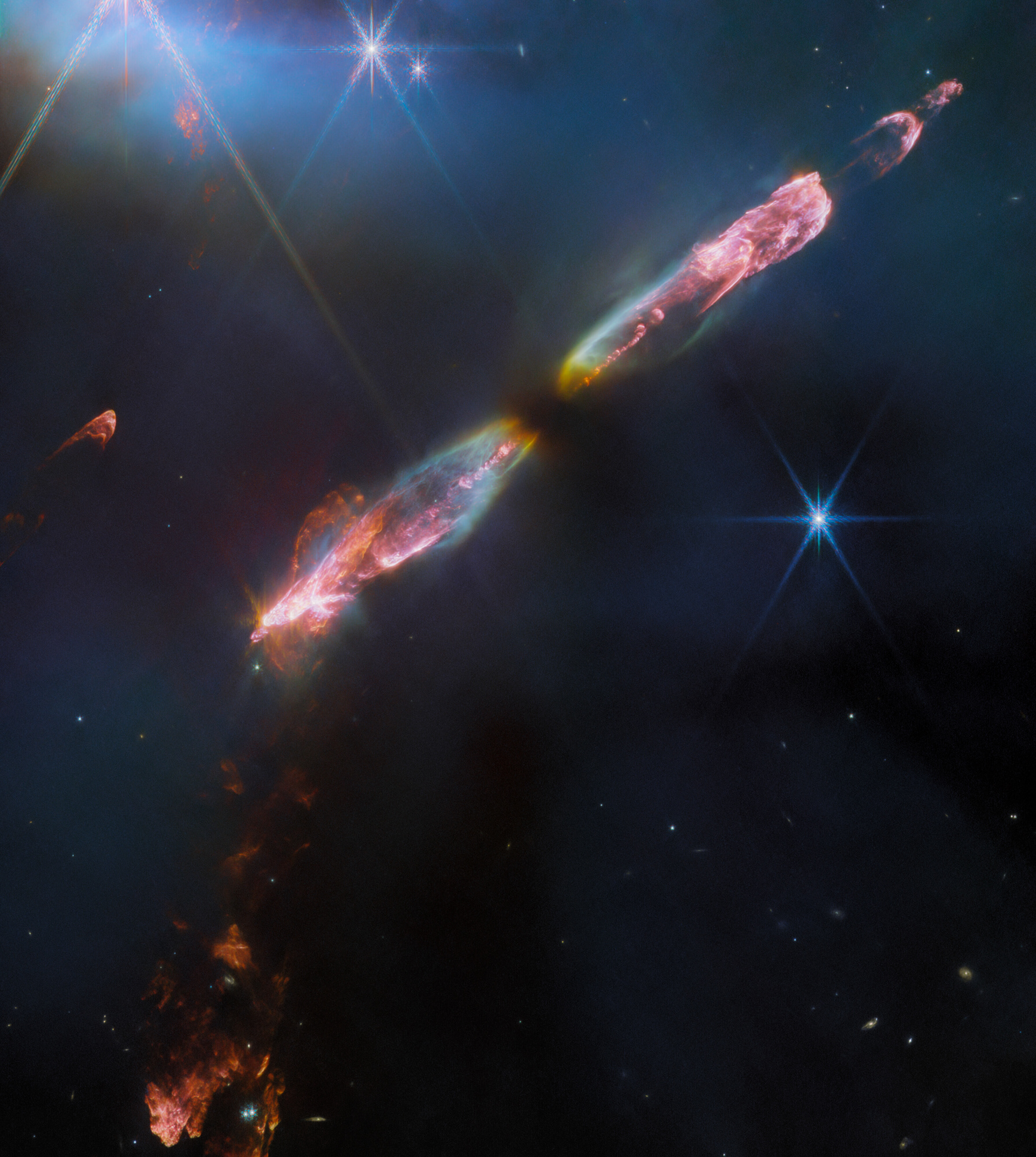

HH 211 (NIRCam image) - Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, T. Ray (Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies)

Rosette Nebula Captured with DECam- Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Image Processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab), D. de Martin & M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab)

Ghostly Stellar Tendrils of the Vela Supernova Remnant Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Image Processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF’s NOIRLab), M. Zamani & D. de Martin (NSF’s NOIRLab)

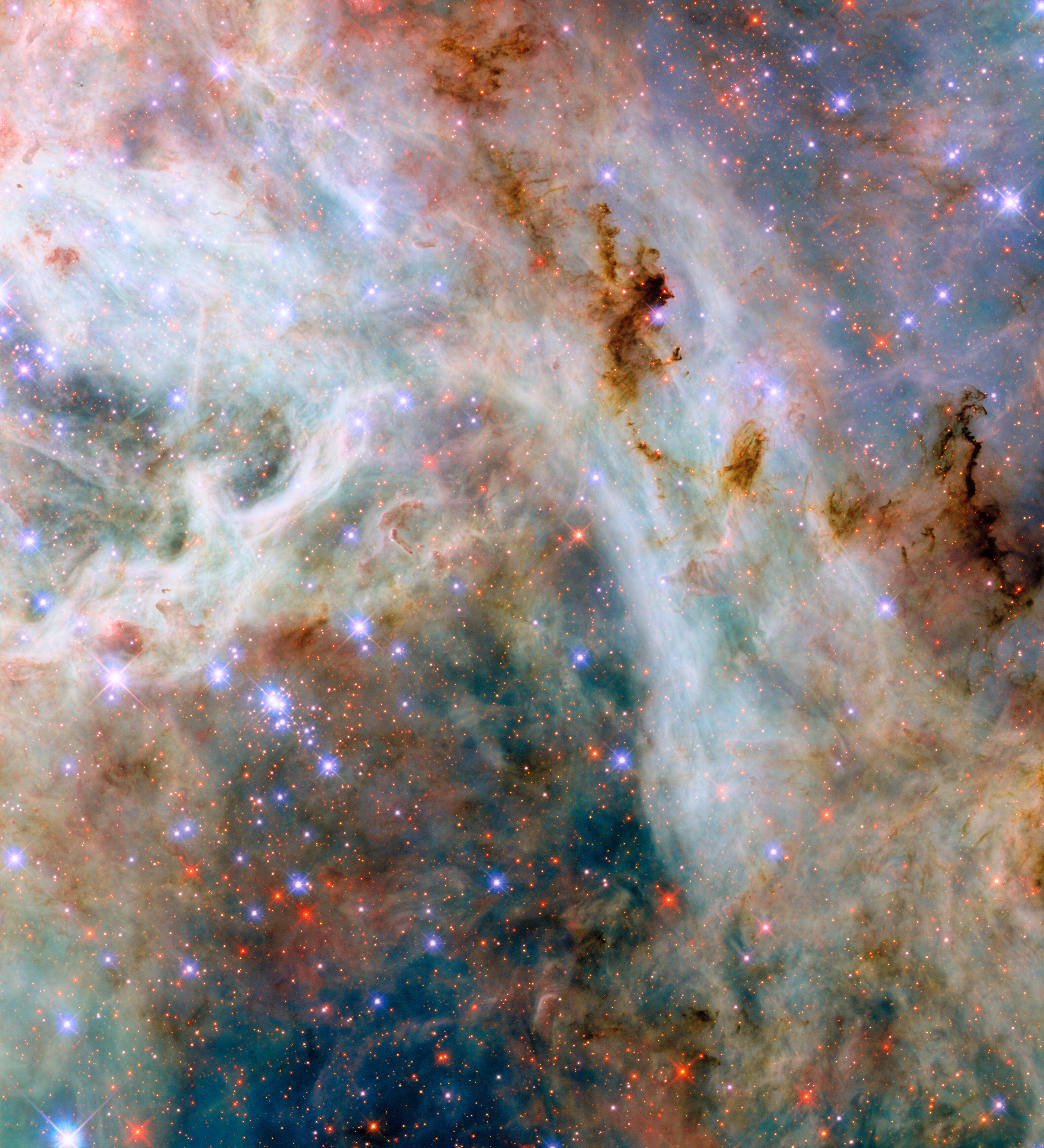

A Tarantula’s outskirts - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, C. Murray

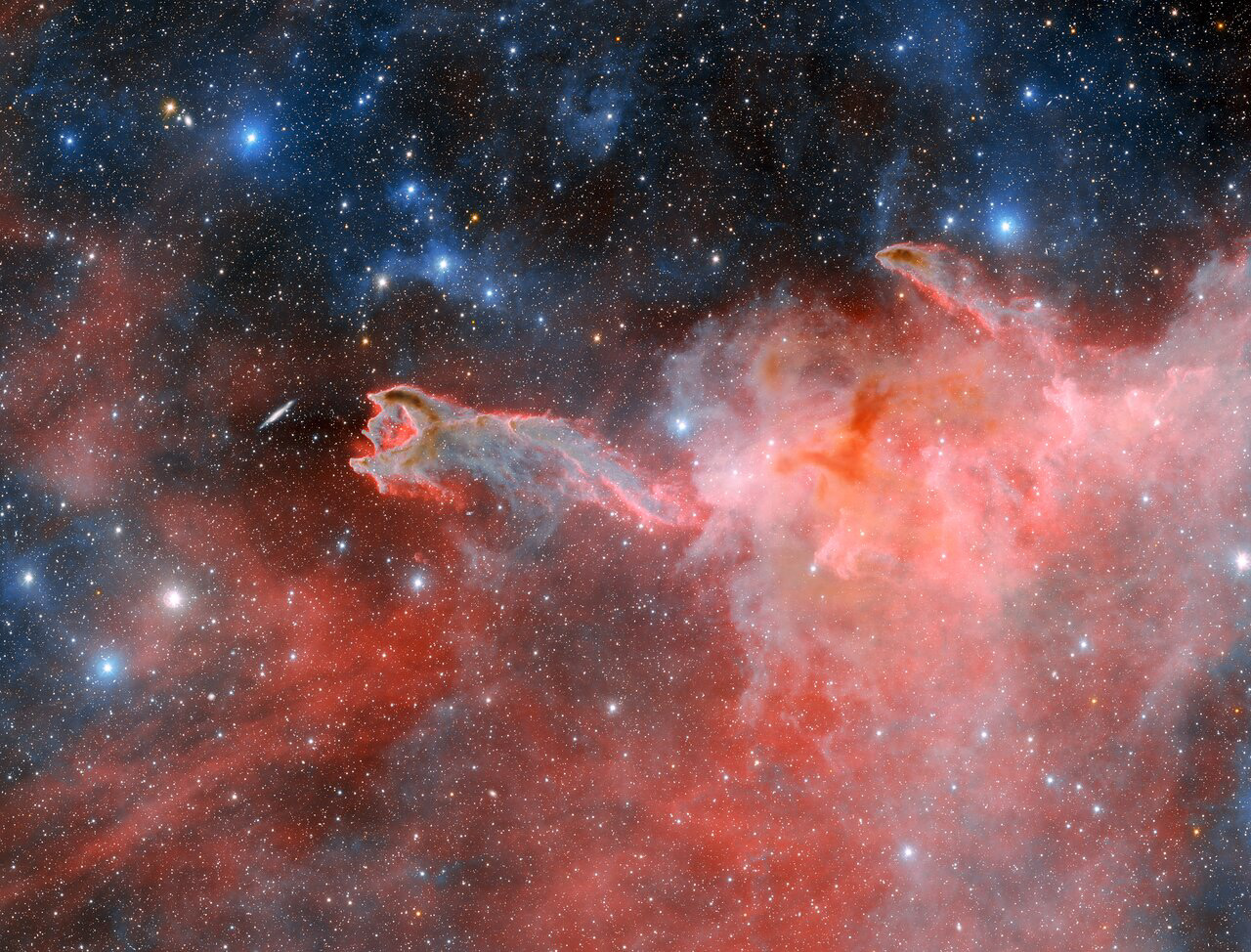

Dark Energy Camera Images Cometary Globule CG 4 Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Image Processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF’s NOIRLab), D. de Martin & M. Zamani (NSF’s NOIRLab)

Snapshot of a peculiar spiral - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, J. Dalcanton, R. J. Foley (UC Santa Cruz), C. Kilpatrick

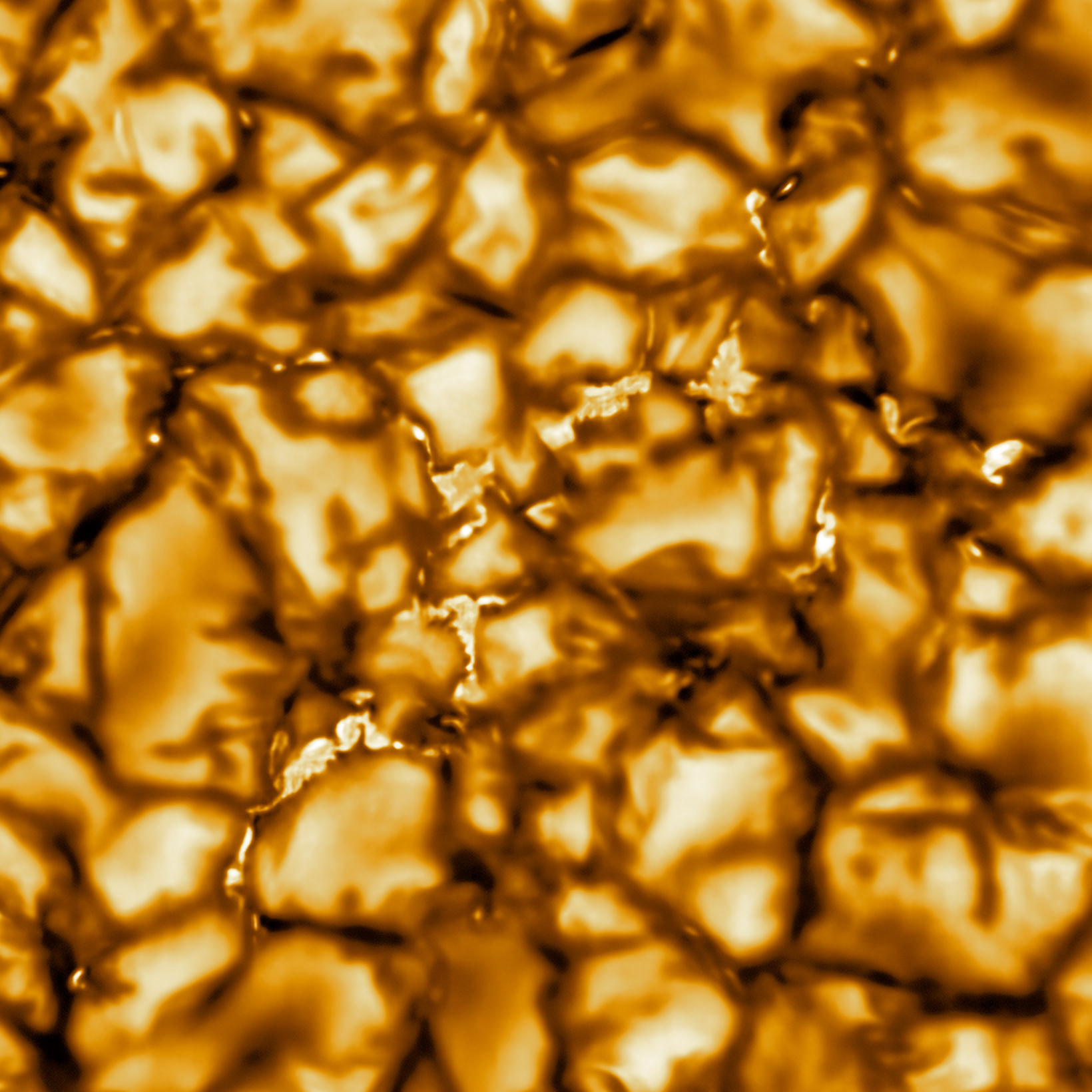

Caption: The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope has produced the highest resolution image of the Sun’s surface ever taken. In this picture taken at 789nm, we can see features as small as 30km (18 miles) in size for the first time ever. The image shows a pattern of turbulent, “boiling” gas that covers the entire sun. The cell-like structures – each about the size of Texas – are the signature of violent motions that transport heat from the inside of the sun to its surface. Hot solar material (plasma) rises in the bright centers of “cells,” cools off and then sinks below the surface in dark lanes in a process known as convection. In these dark lanes we can also see the tiny, bright markers of magnetic fields. Never before seen to this clarity, these bright specks are thought to channel energy up into the outer layers of the solar atmosphere called the corona. These bright spots may be at the core of why the solar corona is more than a million degrees! This image covers an area 8,200 × 8,200 km (5,000 × 5,000 miles, 11 × 11 arcseconds). Credit: NSO/AURA/NSF

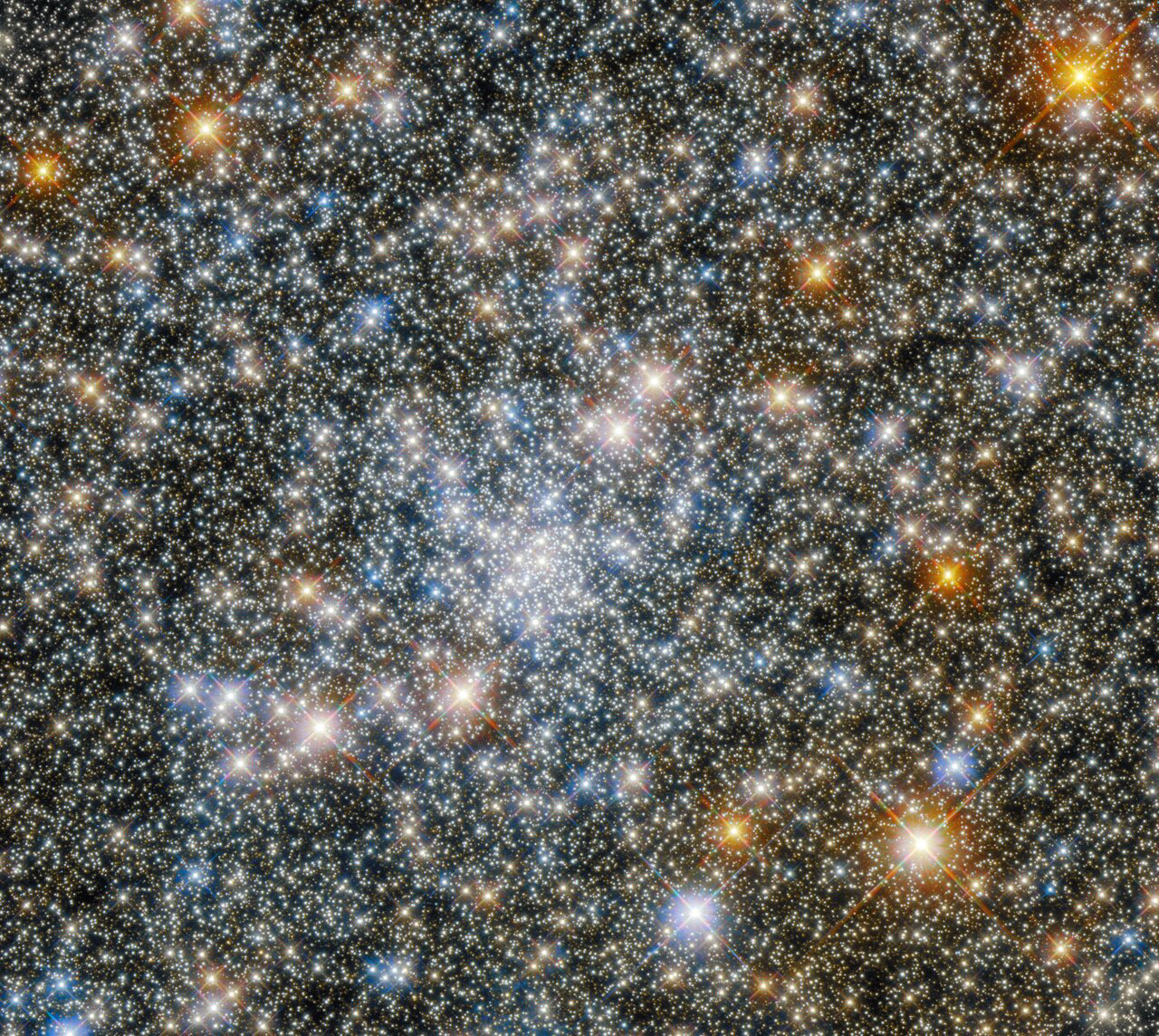

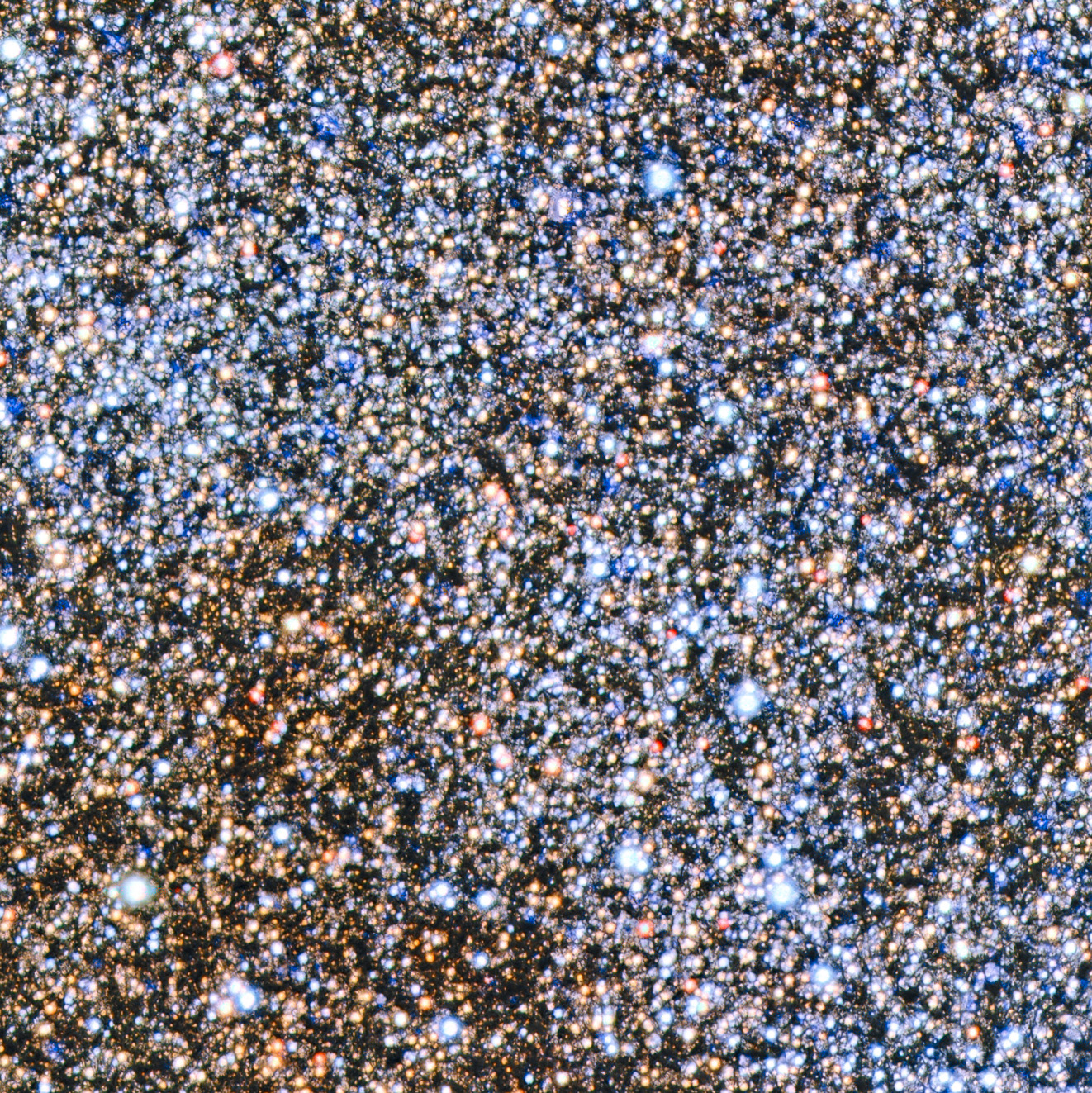

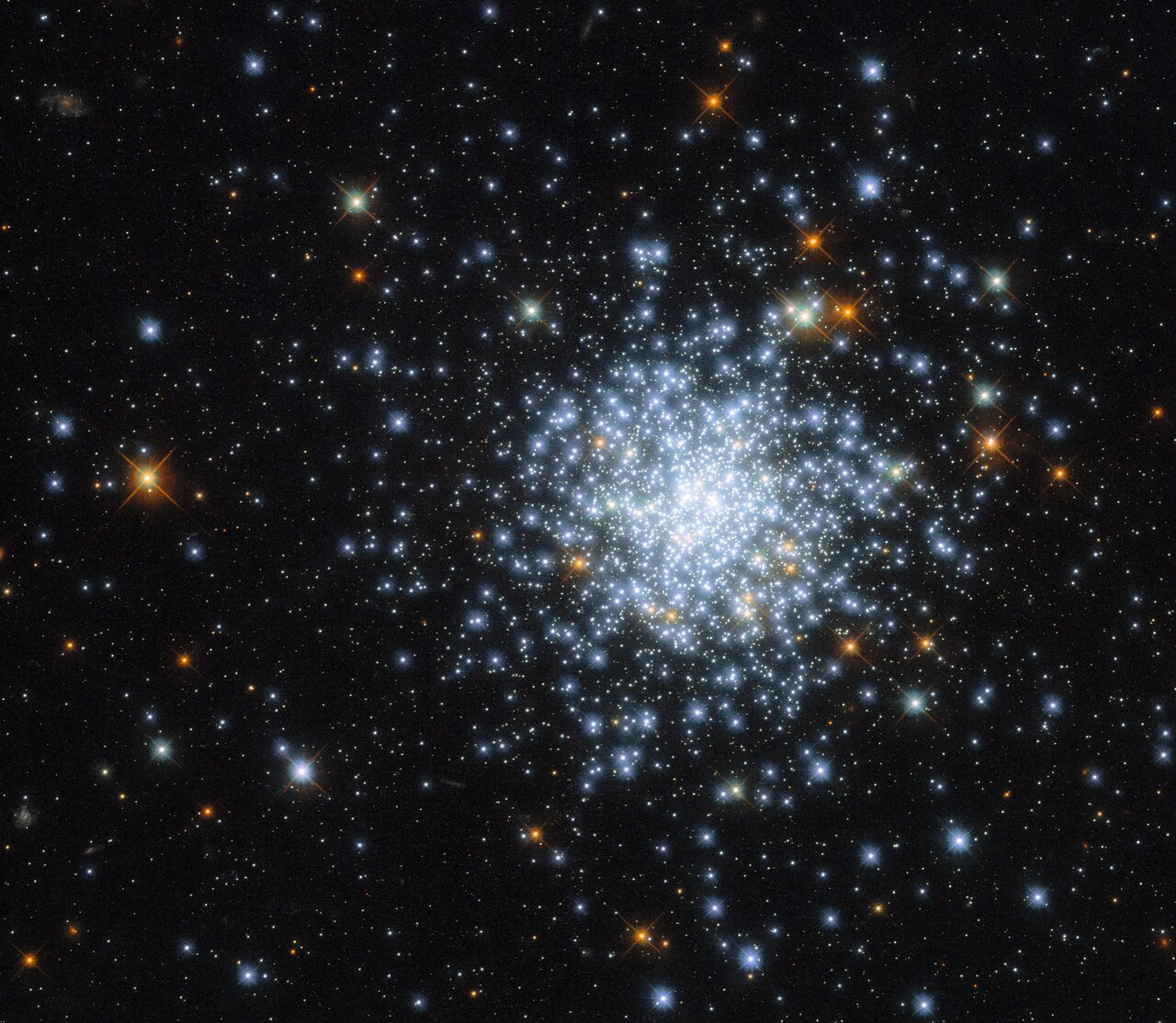

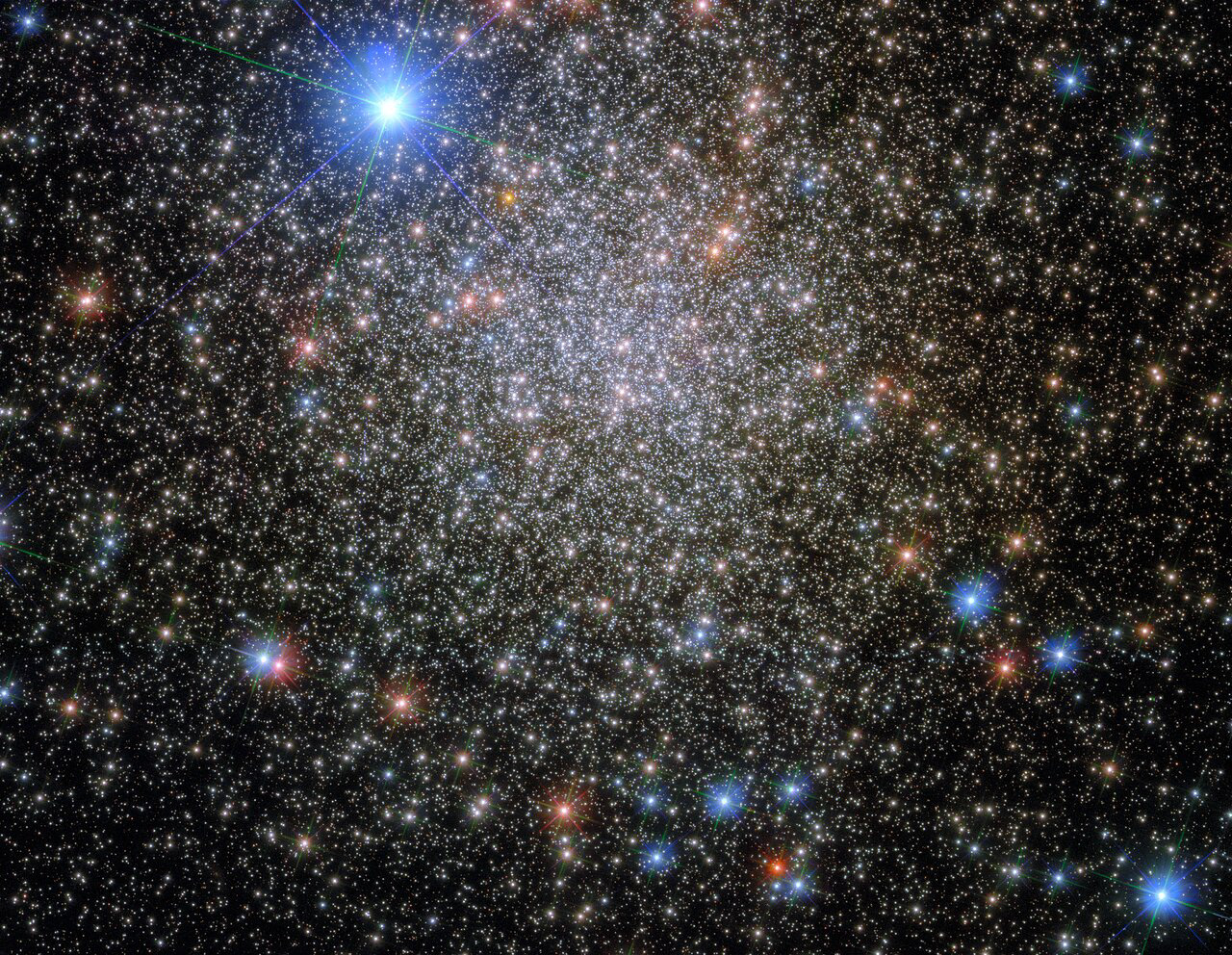

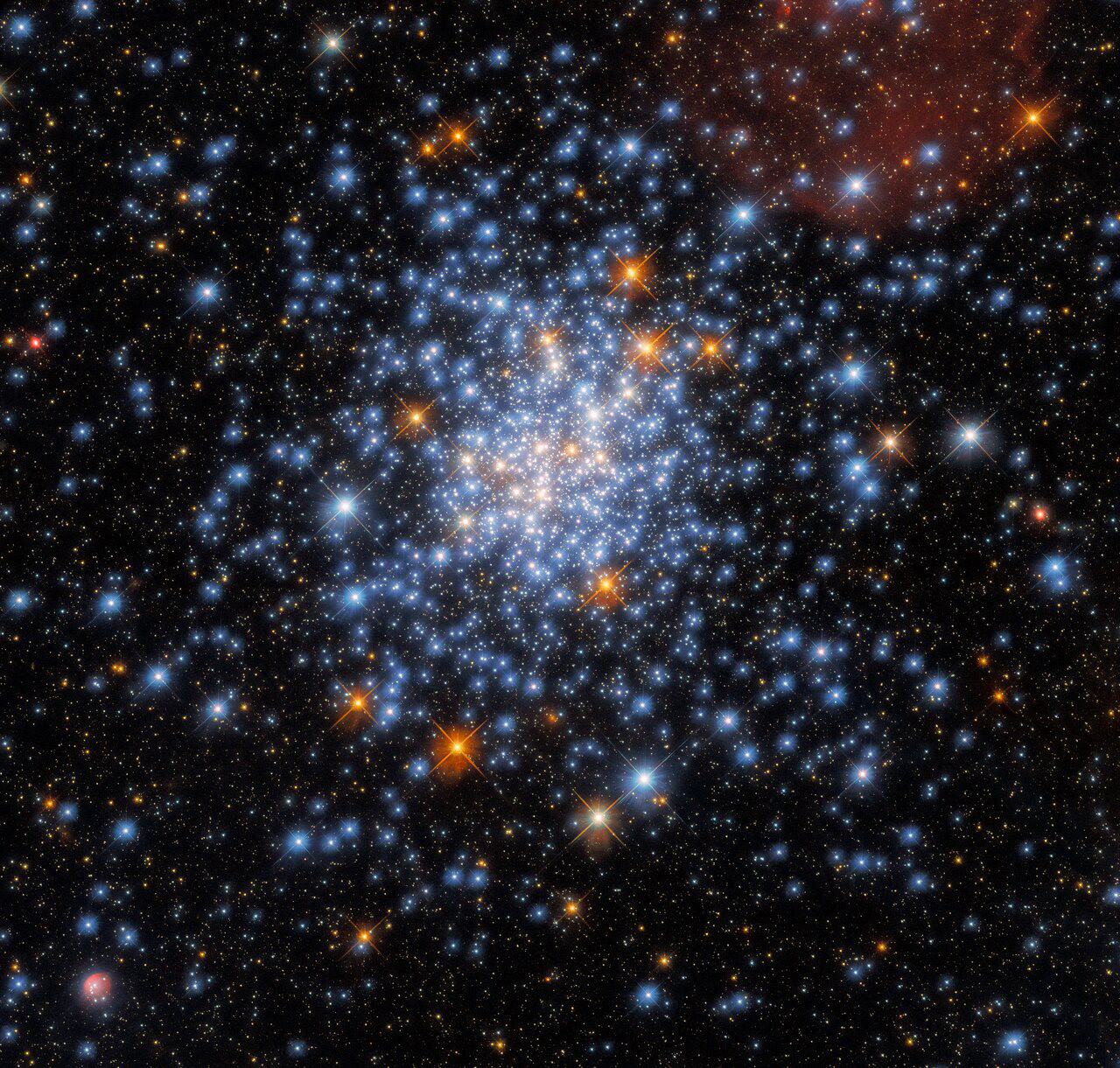

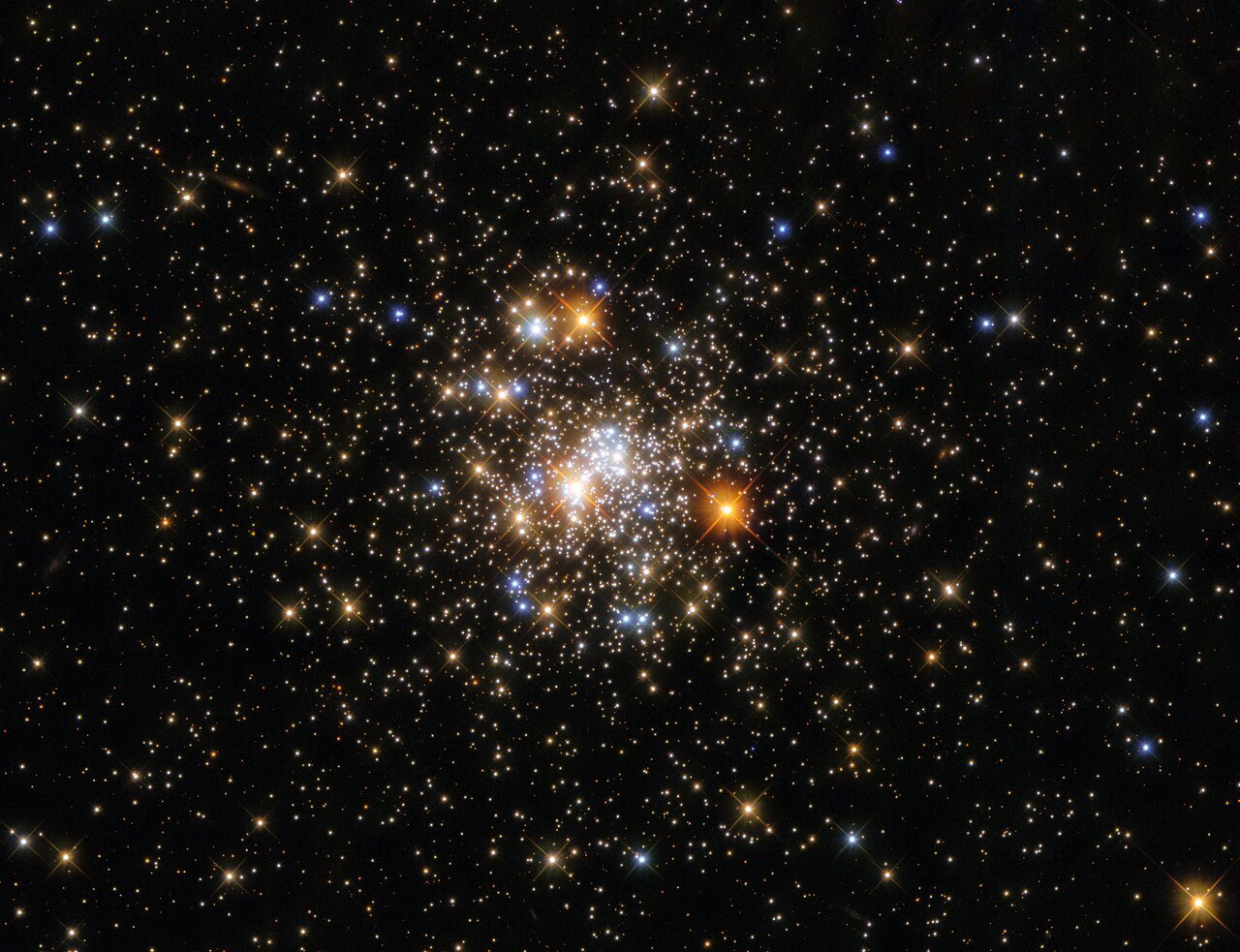

Stellar Snowflakes / Almost like snowflakes, the stars of the globular cluster NGC 6441 sparkle peacefully in the night sky, about 13 000 light-years from the Milky Way’s galactic centre. Like snowflakes, the exact number of stars in such a cluster is difficult to discern. It is estimated that together the stars weigh 1.6 million times the mass of the Sun, making NGC 6441 one of the most massive and luminous globular clusters in the Milky Way. NGC 6441 is host to four pulsars that each complete a single rotation in a few milliseconds. Also hidden within this cluster is JaFu 2, a planetary nebula. Despite its name, this has little to do with planets. A phase in the evolution of intermediate-mass stars, planetary nebulae last for only a few tens of thousands of years, the blink of an eye on astronomical timescales. There are about 150 known globular clusters in the Milky Way. Globular clusters contain some of the first stars to be produced in a galaxy, but the details of their origins and evolution still elude astronomers. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, G. Piotto

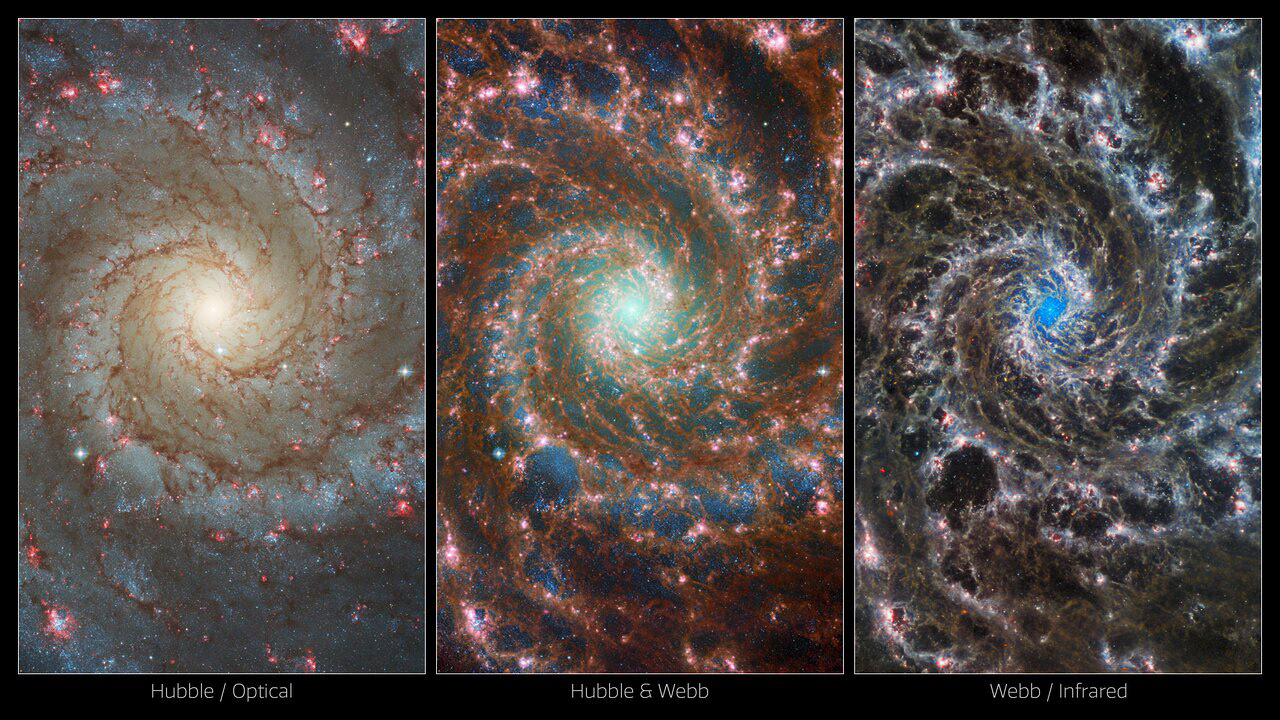

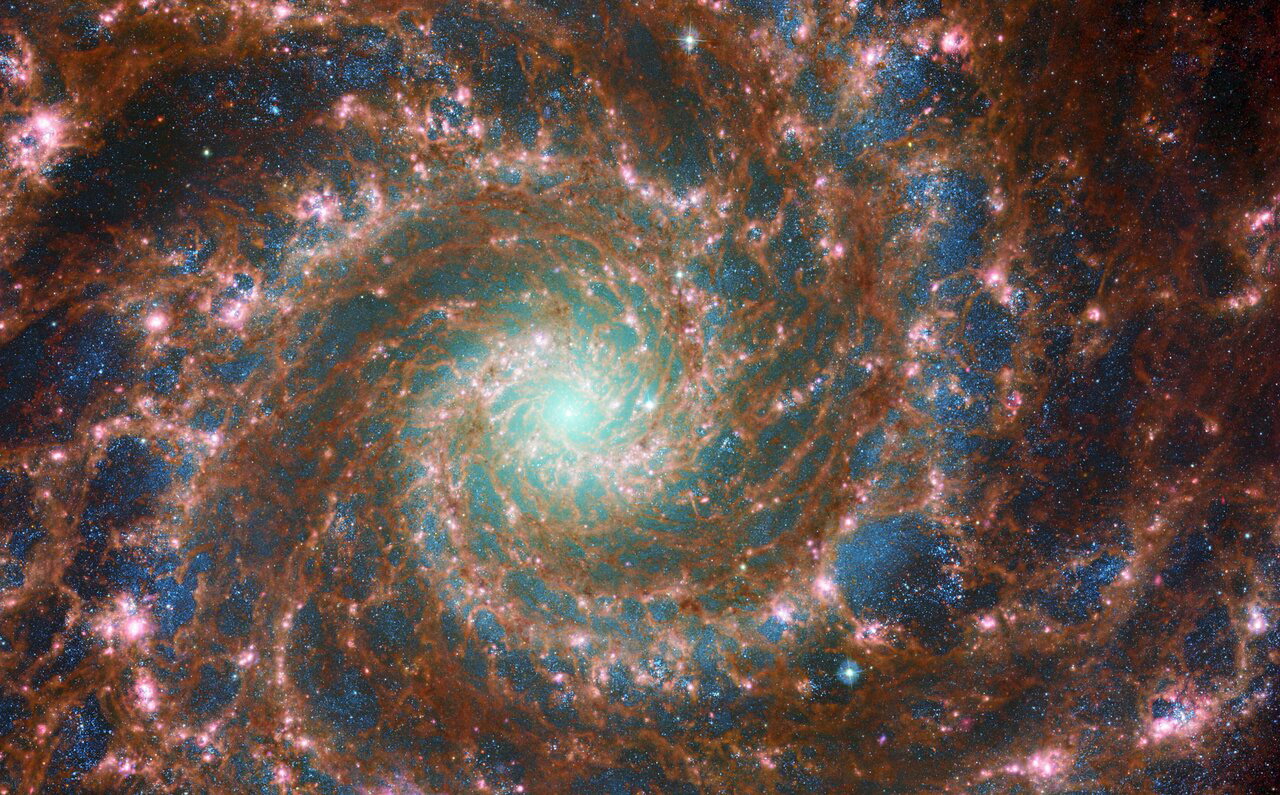

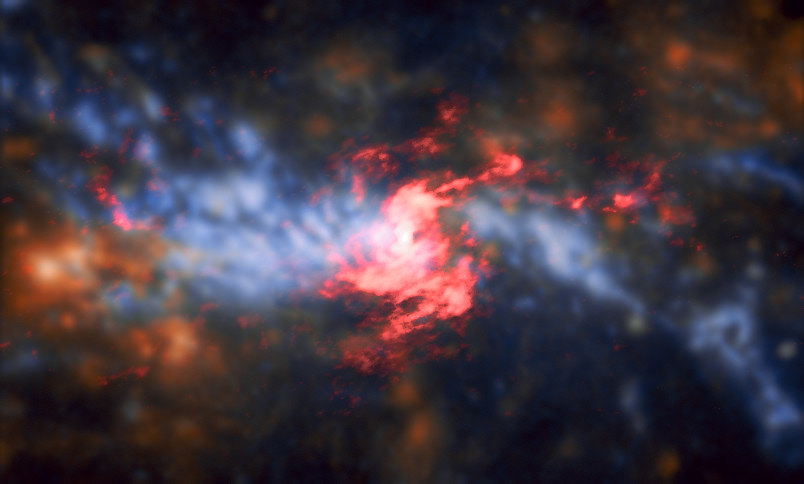

M74 shines at its brightest in this combined optical/mid-infrared image, featuring data from both the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope. With Hubble’s venerable Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and Webb’s powerful Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) capturing a range of wavelengths, this new image has remarkable depth. The red colours mark dust threaded through the arms of the galaxy, lighter oranges being areas of hotter dust. The young stars throughout the arms and the nuclear core are picked out in blue. Heavier, older stars towards the galaxy’s centre are shown in cyan and green, projecting a spooky glow from the core of the Phantom Galaxy. Bubbles of star formation are also visible in pink across the arms. Such a variety of galactic features is rare to see in a single image. Scientists combine data from telescopes operating across the electromagnetic spectrum to truly understand astronomical objects. In this way, data from Hubble and Webb compliment each other to provide a comprehensive view of the spectacular M74 galaxy. Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, J. Lee and the PHANGS-JWST Team; ESA/Hubble & NASA, R. Chandar

![This image by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope’s Near-InfraRed Camera (NIRCam) features the central region of the Chameleon I dark molecular cloud, which resides 630 light years away. The cold, wispy cloud material (blue, centre) is illuminated in the infrared by the glow of the young, outflowing protostar Ced 110 IRS 4 (orange, upper left). The light from numerous background stars, seen as orange dots behind the cloud, can be used to detect ices in the cloud, which absorb the starlight passing through them. An international team of astronomers has reported the discovery of diverse ices in the darkest, coldest regions of a molecular cloud measured to date by studying this region. This result allows astronomers to examine the simple icy molecules that will be incorporated into future exoplanets, while opening a new window on the origin of more complex molecules that are the first step in the creation of the building blocks of life. [Image Description: A large, dark cloud is contained within the frame. In its top half it is textured like smoke and has wispy gaps, while at the bottom and at the sides it fades gradually out of view. On the left are several orange stars: three each with six large spikes, and one behind the cloud which colours it pale blue and orange. Many tiny stars are visible, and the background is black.] Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and M. Zamani (ESA/Webb); Science: F. Sun (Steward Observatory), Z. Smith (Open University), and the Ice Age ERS Team.](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

This image by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope’s Near-InfraRed Camera (NIRCam) features the central region of the Chameleon I dark molecular cloud, which resides 630 light years away. The cold, wispy cloud material (blue, centre) is illuminated in the infrared by the glow of the young, outflowing protostar Ced 110 IRS 4 (orange, upper left). The light from numerous background stars, seen as orange dots behind the cloud, can be used to detect ices in the cloud, which absorb the starlight passing through them. An international team of astronomers has reported the discovery of diverse ices in the darkest, coldest regions of a molecular cloud measured to date by studying this region. This result allows astronomers to examine the simple icy molecules that will be incorporated into future exoplanets, while opening a new window on the origin of more complex molecules that are the first step in the creation of the building blocks of life. [Image Description: A large, dark cloud is contained within the frame. In its top half it is textured like smoke and has wispy gaps, while at the bottom and at the sides it fades gradually out of view. On the left are several orange stars: three each with six large spikes, and one behind the cloud which colours it pale blue and orange. Many tiny stars are visible, and the background is black.] Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and M. Zamani (ESA/Webb); Science: F. Sun (Steward Observatory), Z. Smith (Open University), and the Ice Age ERS Team.

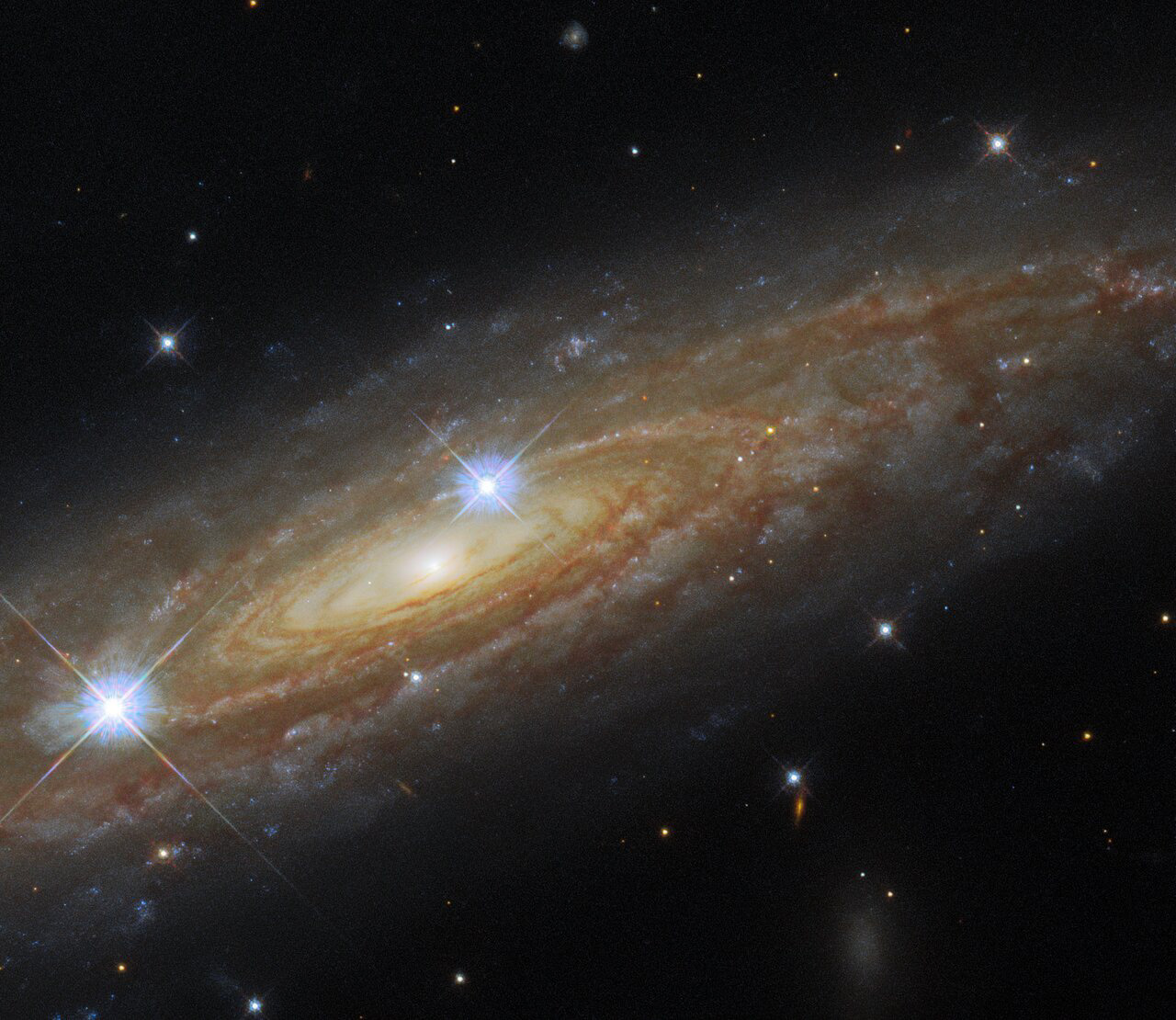

This stunning image features NGC 3198, a galaxy that lies about 47 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major. This image was taken with the Mosaic instrument on the 4-meter Nicholas U. Mayall Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab, and shows the full extent of the galaxy, from the bright central bulge to the tenuous outer reaches of the tightly-wound spiral arms. Almost all the objects lurking in the background are galaxies or galaxy clusters — a sea of distant galaxies of all shapes, sizes, and orientations. Accurately measuring the distance to an astronomical object — everything from our own Sun to galaxies such as NGC 3198 — is an age-old challenge for astronomers, and requires a combination of measurements and methods. The galaxy at the heart of this image has played a part in this astronomical undertaking by allowing astronomers to calibrate astronomical distance measurements based on a type of variable star known as a Cepheid variable. Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA. Acknowledgments: PI: M T. Patterson (New Mexico State University) Image processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

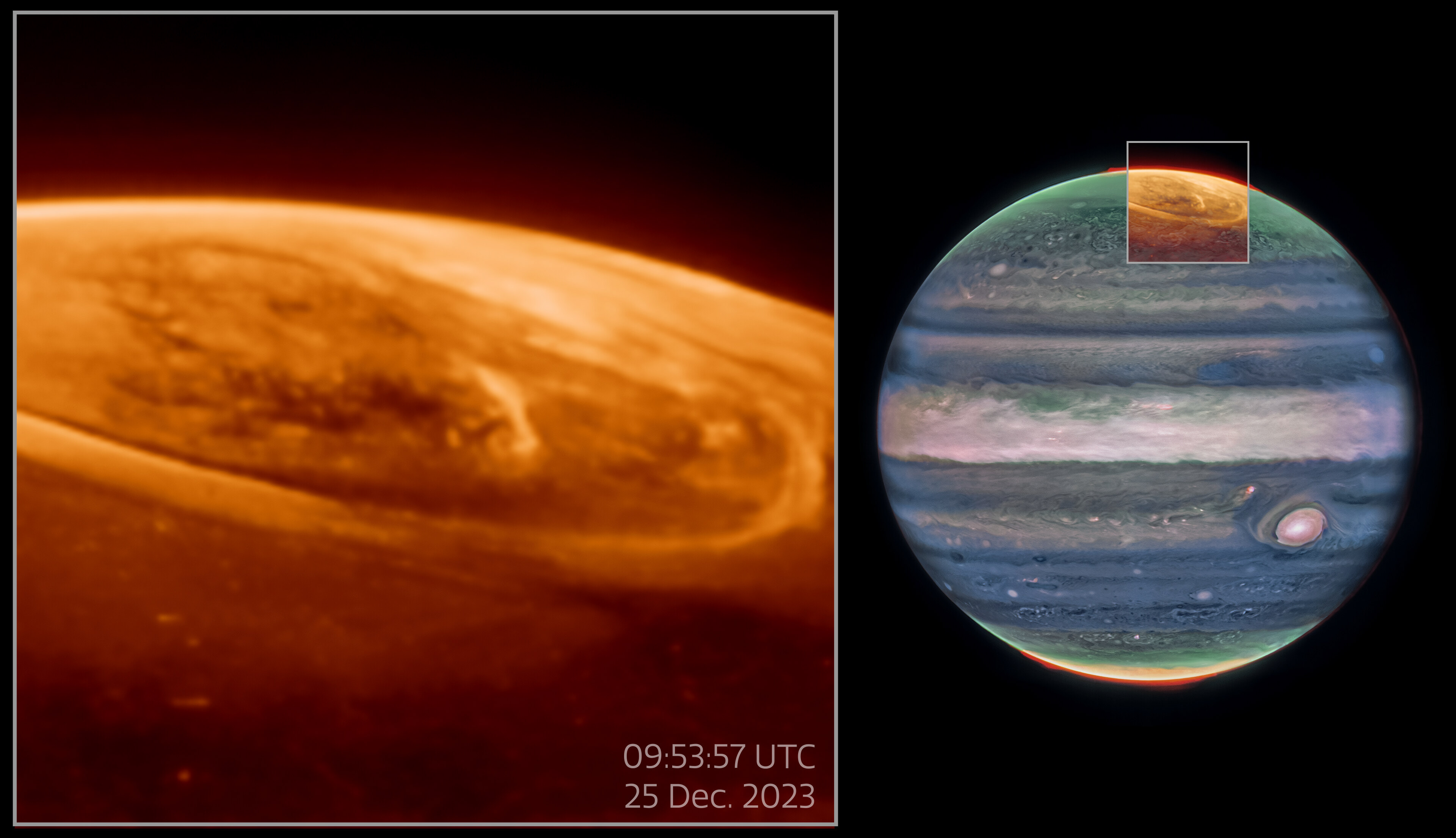

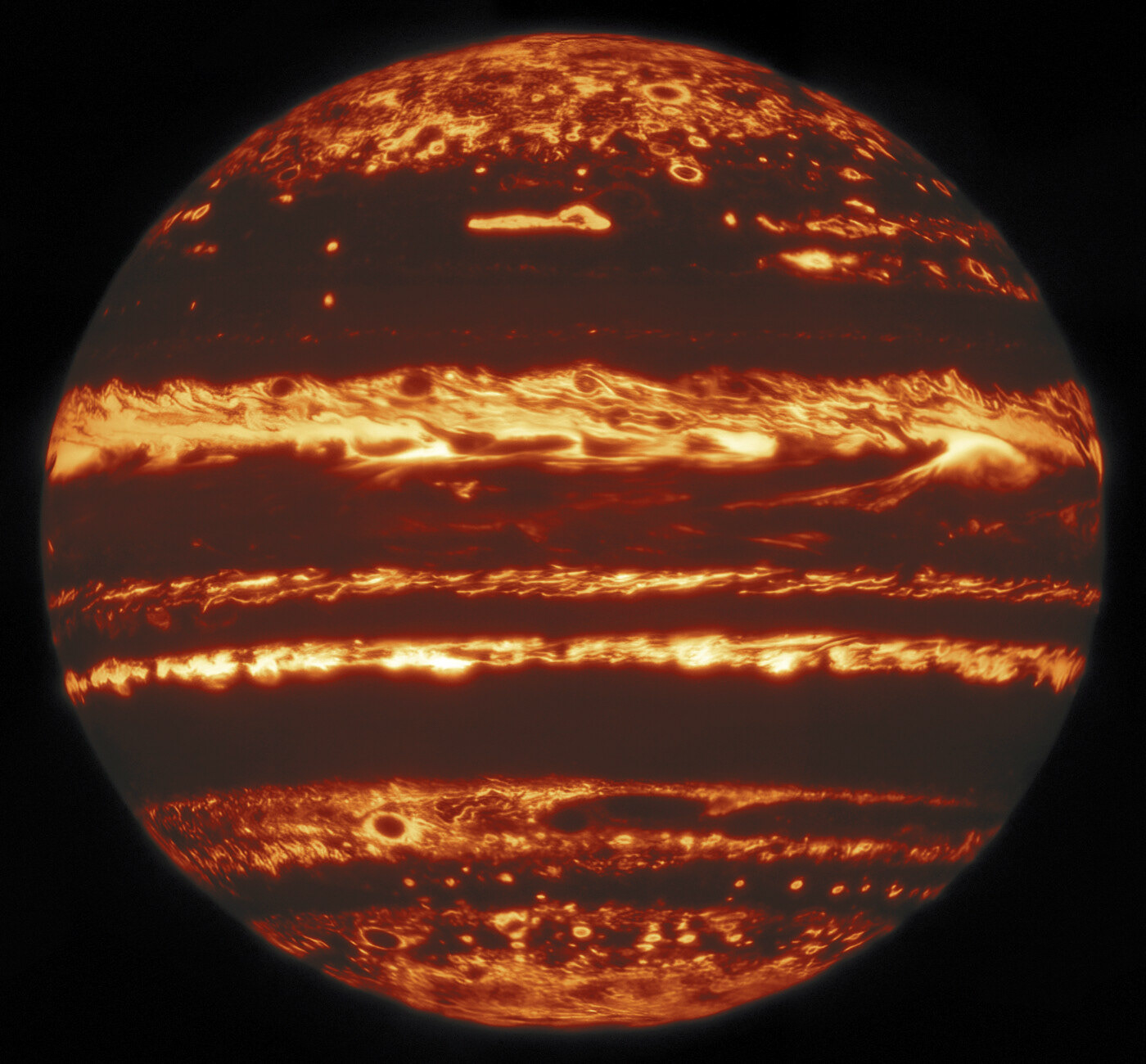

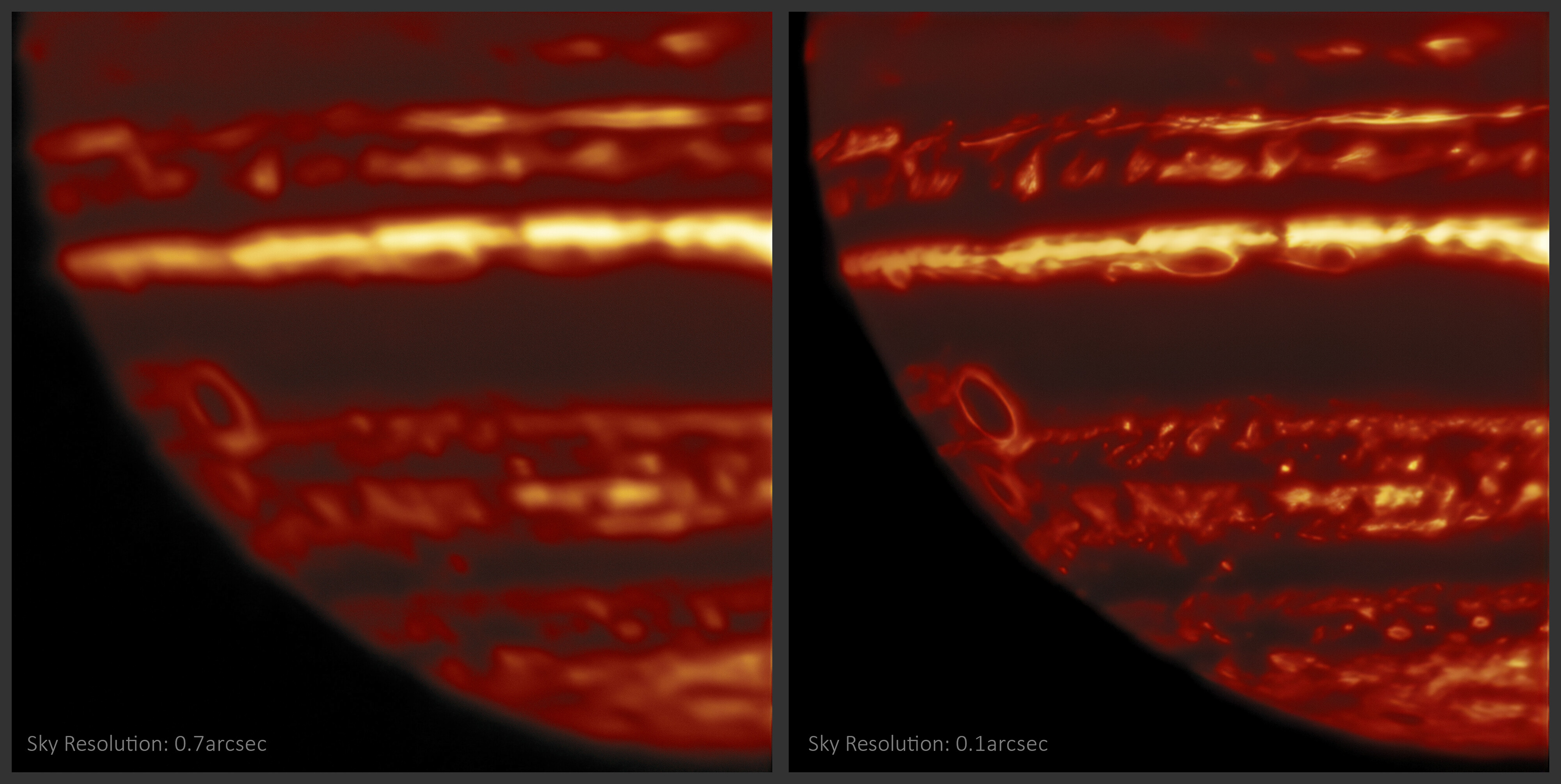

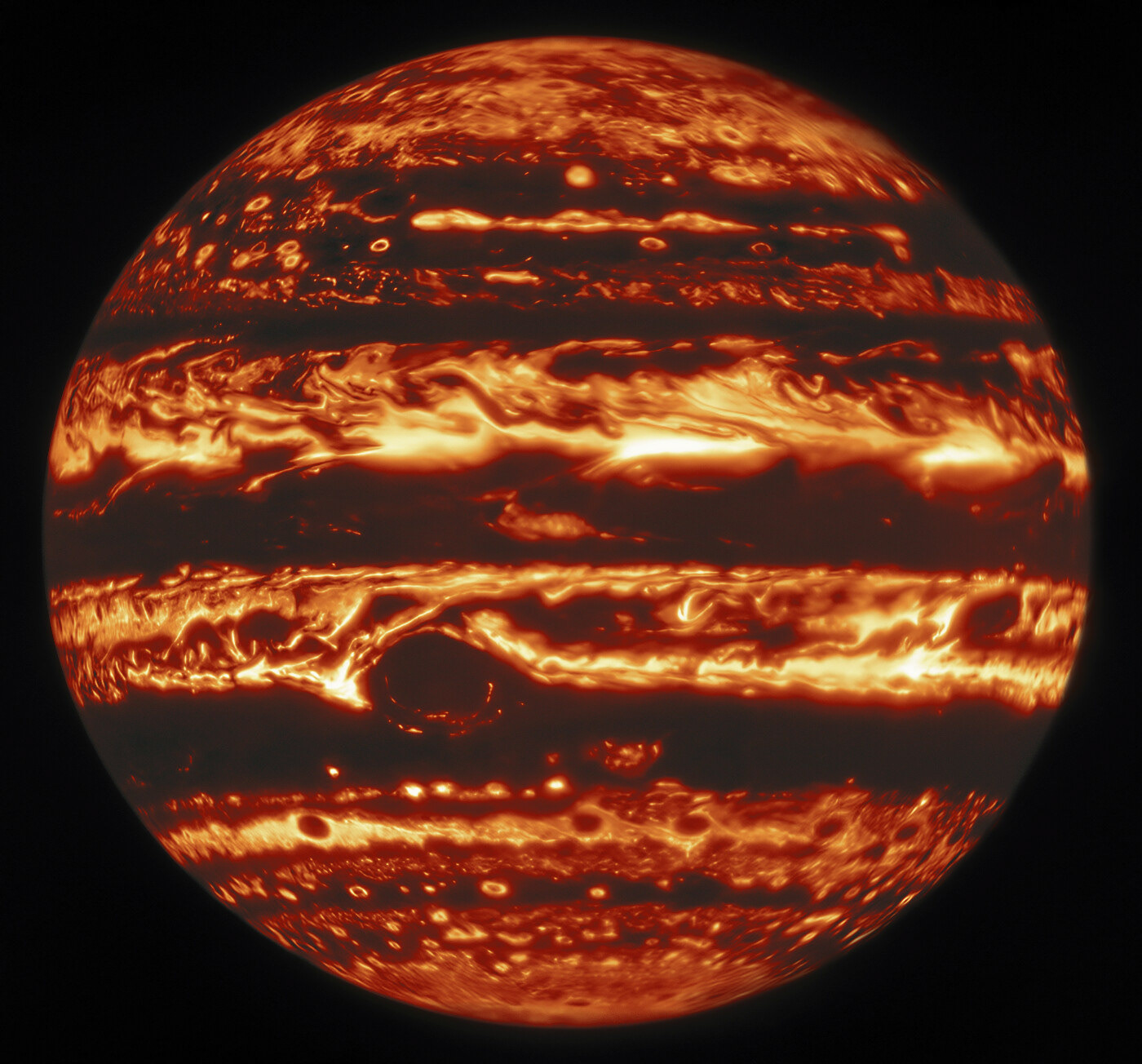

This image showing the entire disk of Jupiter in infrared light was compiled from a mosaic of nine separate pointings observed by the international Gemini Observatory, a program of NSF’s NOIRLab on 29 May 2019. From a “lucky imaging” set of 38 exposures taken at each pointing, the research team selected the sharpest 10%, combining them to image one ninth of Jupiter’s disk. Stacks of exposures at the nine pointings were then combined to make one clear, global view of the planet. Even though it only takes a few seconds for Gemini to create each image in a lucky imaging set, completing all 38 exposures in a set can take minutes — long enough for features to rotate noticeably across the disk. In order to compare and combine the images, they are first mapped to their actual latitude and longitude on Jupiter, using the limb, or edge of the disk, as a reference. Once the mosaics are compiled into a full disk, the final images are some of the highest-resolution infrared views of Jupiter ever taken from the ground. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, M.H. Wong (UC Berkeley) and team Acknowledgments: Mahdi Zamani

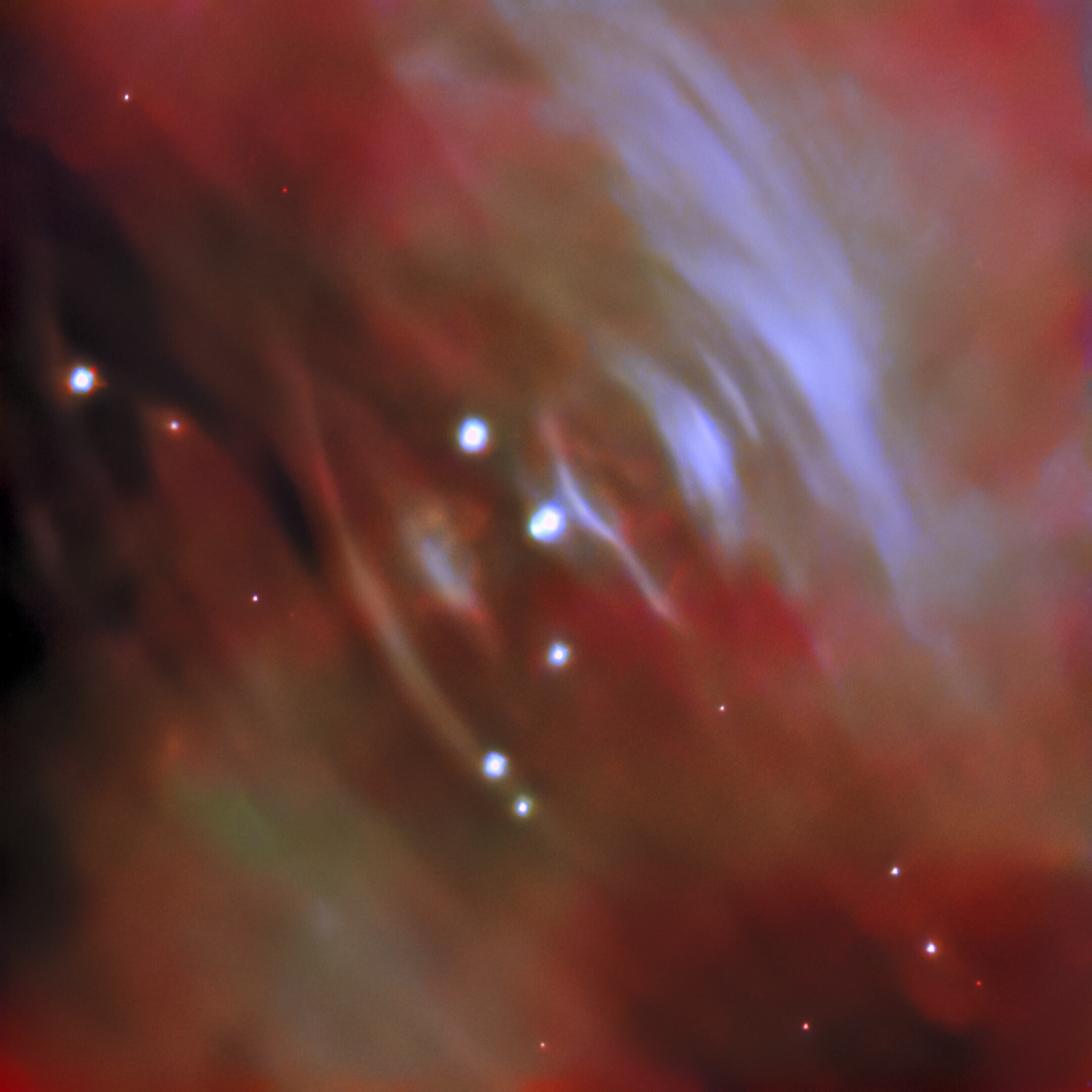

A 50-trillion-km (33-trillion-mile, or 5 light-year) long section of the western wall in the Carina Nebula, as observed with adaptive optics on the Gemini South telescope. This mountainous section of the nebula reveals a number of unusual structures including a long series of parallel ridges that could be produced by a magnetic field, a remarkable almost perfectly smooth wave, and fragments that appear to be in the process of being sheared off the cloud by a strong wind. There is also evidence for a jet of material ejected from a newly-formed star. The exquisite detail seen in the image is in part due to a technology known as adaptive optics, which resulted in a ten-fold improvement in the resolution of the research team’s observations. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgment: PI: Patrick Hartigan (Rice University) Image processing: Patrick Hartigan (Rice University), Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

Comet-like stars This spectacular Picture of the Week was produced from data gathered by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, combined with data from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. It shows a cluster of stars named Westerlund 1, one of the most massive young star clusters known to reside in the Milky Way. Excitingly, it also shows the comet-like “tails” of material stretching away from some of the giant stars in Westerlund 1. Such tails are formed in the thick, relentless winds that pour from the cluster’s stellar residents, carrying material outwards. This phenomenon is similar to how comets get their famous and beautiful tails. Comet tails in the Solar System are driven away from the nucleus of their parent comet by a wind of particles that streams out from the Sun. Consequently comet tails always point away from our Sun. Similarly, the tails of the huge red stars shown in this image point away from the core of the cluster, likely the result of powerful cluster winds generated by the hundreds of hot and massive stars found towards the centre of Westerlund 1. These massive structures cover large distances and indicate the dramatic effect the environment can have on how the stars form and evolve. These comet-like tails were detected during an ALMA study of Westerlund 1 that aimed to explore the cluster’s constituent stars and figure out how, and at what rate, they lose their mass. The cluster is known to host a large amount of massive stars, many of them intriguing and rare types, making it of great interest and use to astronomers wishing to understand the myriad stars in our galaxy. Credit: ESO/D. Fenech et al.; ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

Cosmic cloudscape - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, C. Murray

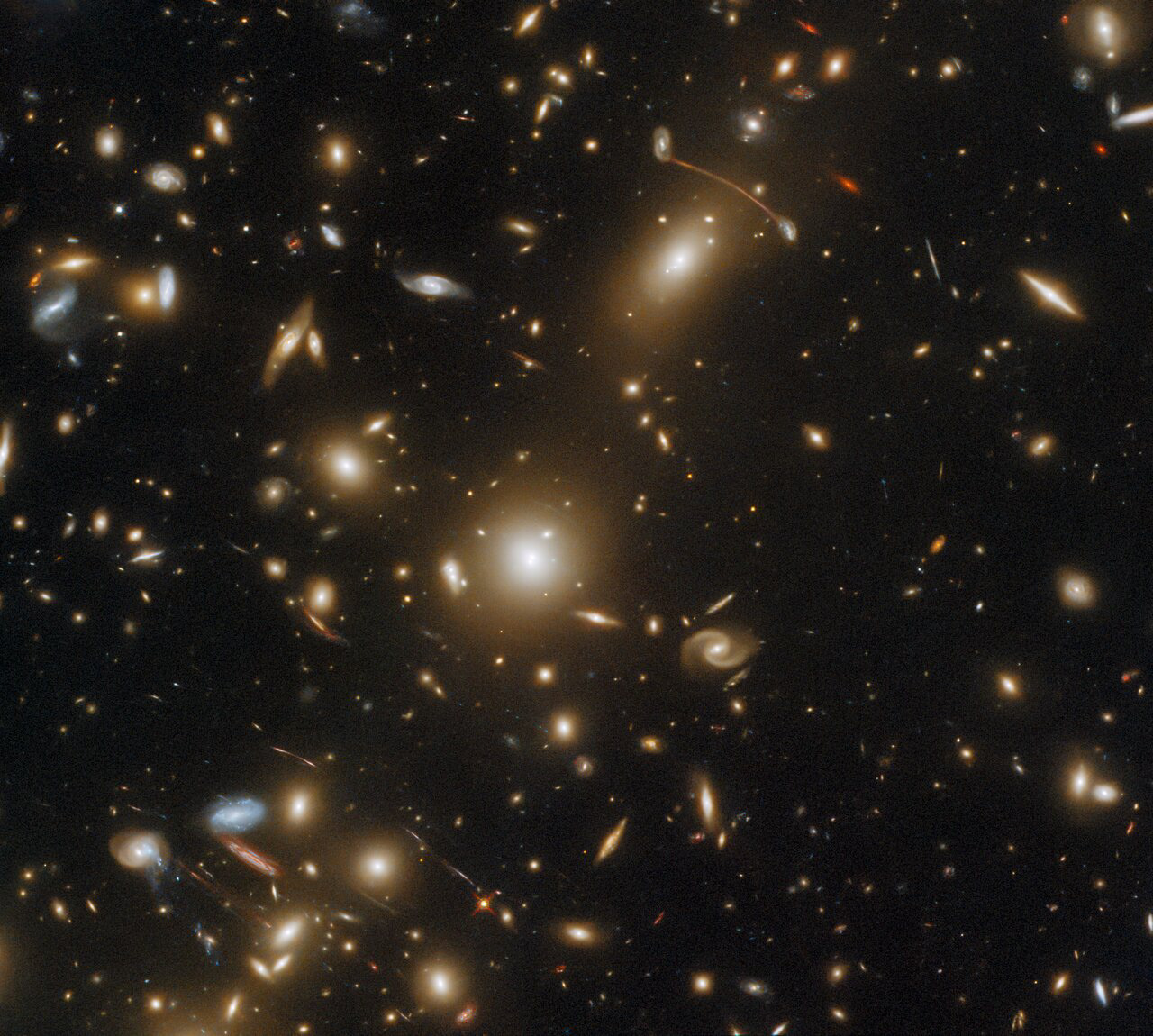

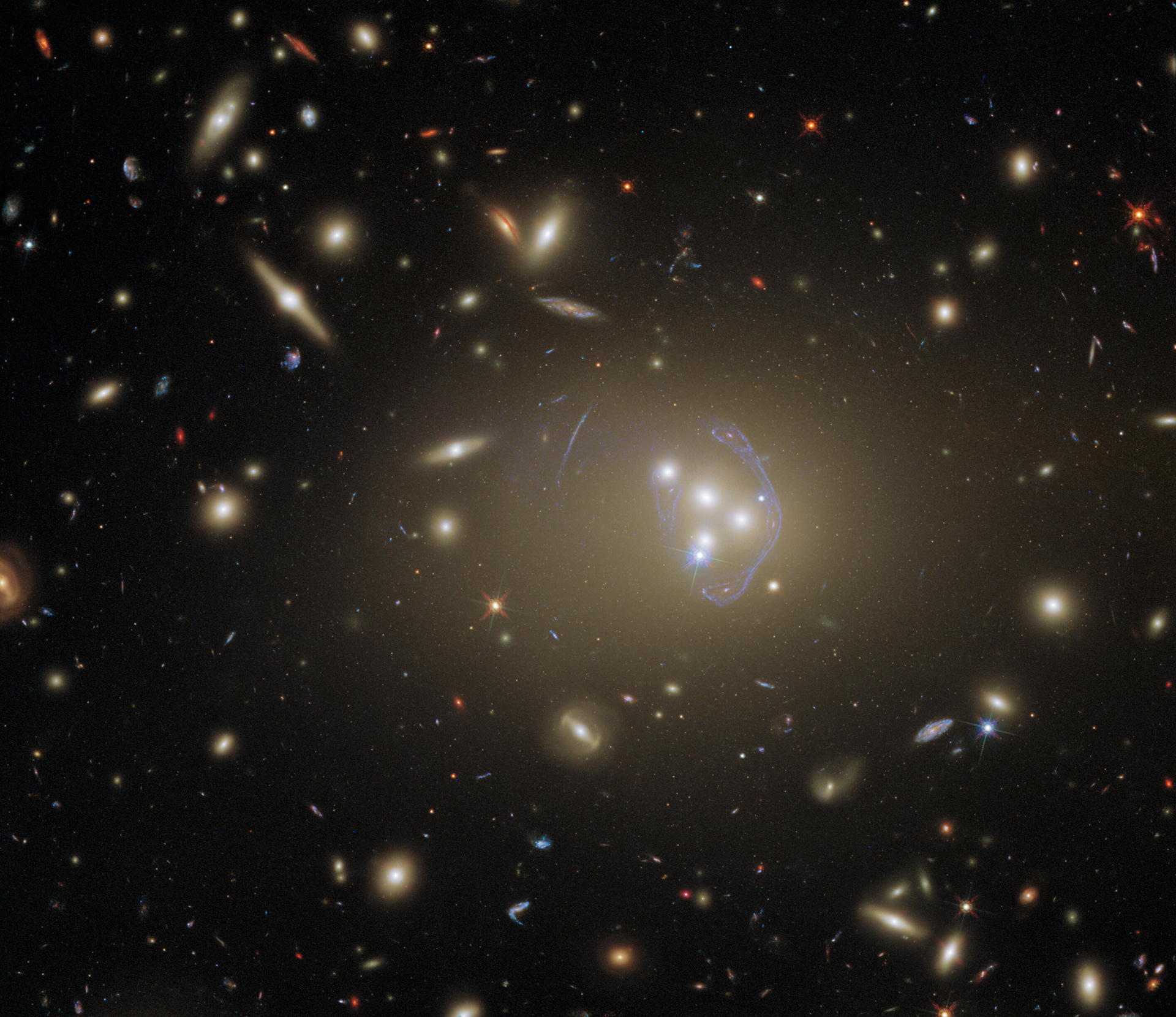

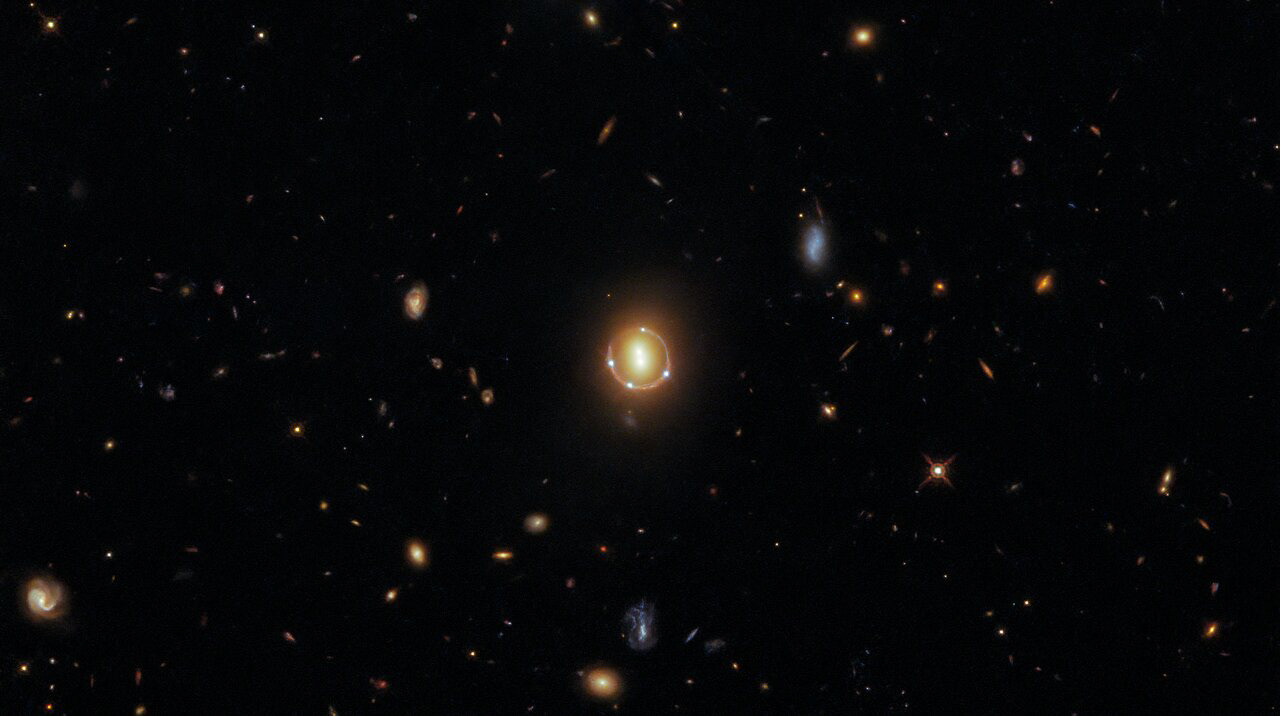

This detailed image features Abell 3827, a galaxy cluster that offers a wealth of exciting possibilities for study. It was observed by Hubble in order to study dark matter, which is one of the greatest puzzles cosmologists face today. The science team used Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) to complete their observations. The two cameras have different specifications and can observe different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, so using them both allowed the astronomers to collect more complete information. Abell 3827 has also been observed previously by Hubble, because of the interesting gravitational lens at its core. Looking at this cluster of hundreds of galaxies, it is amazing to recall that until less than 100 years ago, many astronomers believed that the Milky Way was the only galaxy in the Universe. The possibility of other galaxies had been debated previously, but the matter was not truly settled until Edwin Hubble confirmed that the Great Andromeda Nebula was in fact far too distant to be part of the Milky Way. The Great Andromeda Nebula became the Andromeda Galaxy, and astronomers recognised that our Universe was much, much bigger than humanity had imagined. We can only imagine how Edwin Hubble — after whom the Hubble Space Telescope was named — would have felt if he’d seen this spectacular image of Abell 3827. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, R. Massey

![The bright variable star V 372 Orionis takes centre stage in this image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, which has also captured a smaller companion star in the upper left of this image. Both stars lie in the Orion Nebula, a colossal region of star formation roughly 1450 light years from Earth. V 372 Orionis is a particular type of variable star known as an Orion Variable. These young stars experience some tempestuous moods and growing pains, which are visible to astronomers as irregular variations in luminosity. Orion Variables are often associated with diffuse nebulae, and V 372 Orionis is no exception; the patchy gas and dust of the Orion Nebula pervade this scene. This image overlays data from two of Hubble’s instruments. Data from the Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Camera 3 at infrared and visible wavelengths were layered to reveal rich details of this corner of the Orion Nebula. Hubble also left its own subtle signature on this astronomical portrait in the form of the diffraction spikes surrounding the bright stars. These prominent artefacts are created by starlight interacting with Hubble’s inner workings, and as a result they reveal hints of Hubble’s structure. The four spikes surrounding the stars in this image are created by four vanes inside Hubble supporting the telescope’s secondary mirror. The diffraction spikes of the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, on the other hand, are six-pointed as a result of Webb’s hexagonal mirror segments and 3-legged support structure for the secondary mirror. [Image description: Two very bright stars with cross-shaped diffraction spikes are prominent: the larger is slightly lower-right of centre, the smaller lies towards the upper-left corner. Small red stars with short diffraction spikes are scattered around them. The background is covered nearly completely by gas: smoky, bright blue gas around the larger star in the centre and lower-right, and wispier red gas elsewhere.] Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, J. Bally, M. Robberto](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

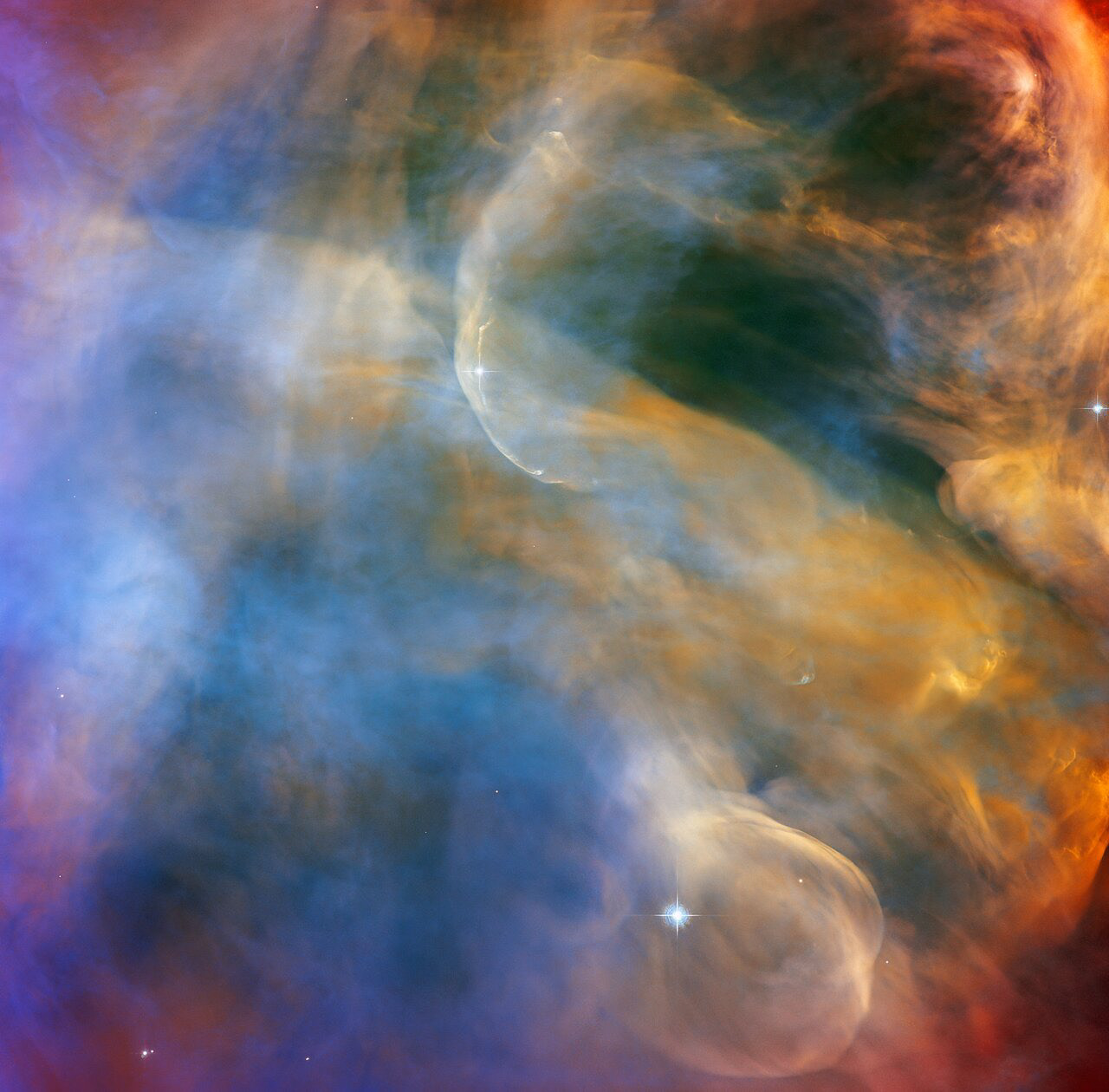

The bright variable star V 372 Orionis takes centre stage in this image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, which has also captured a smaller companion star in the upper left of this image. Both stars lie in the Orion Nebula, a colossal region of star formation roughly 1450 light years from Earth. V 372 Orionis is a particular type of variable star known as an Orion Variable. These young stars experience some tempestuous moods and growing pains, which are visible to astronomers as irregular variations in luminosity. Orion Variables are often associated with diffuse nebulae, and V 372 Orionis is no exception; the patchy gas and dust of the Orion Nebula pervade this scene. This image overlays data from two of Hubble’s instruments. Data from the Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Camera 3 at infrared and visible wavelengths were layered to reveal rich details of this corner of the Orion Nebula. Hubble also left its own subtle signature on this astronomical portrait in the form of the diffraction spikes surrounding the bright stars. These prominent artefacts are created by starlight interacting with Hubble’s inner workings, and as a result they reveal hints of Hubble’s structure. The four spikes surrounding the stars in this image are created by four vanes inside Hubble supporting the telescope’s secondary mirror. The diffraction spikes of the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, on the other hand, are six-pointed as a result of Webb’s hexagonal mirror segments and 3-legged support structure for the secondary mirror. [Image description: Two very bright stars with cross-shaped diffraction spikes are prominent: the larger is slightly lower-right of centre, the smaller lies towards the upper-left corner. Small red stars with short diffraction spikes are scattered around them. The background is covered nearly completely by gas: smoky, bright blue gas around the larger star in the centre and lower-right, and wispier red gas elsewhere.] Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, J. Bally, M. Robberto

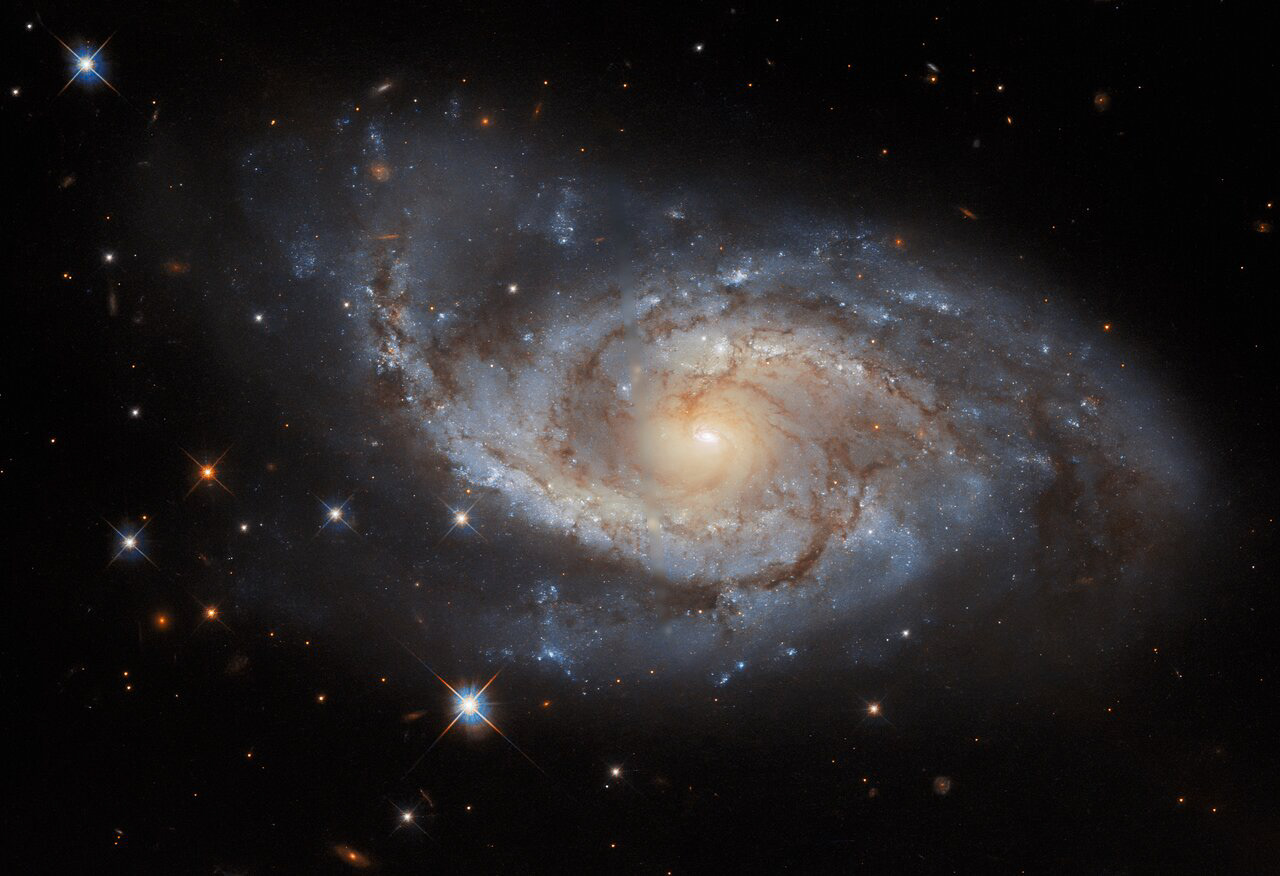

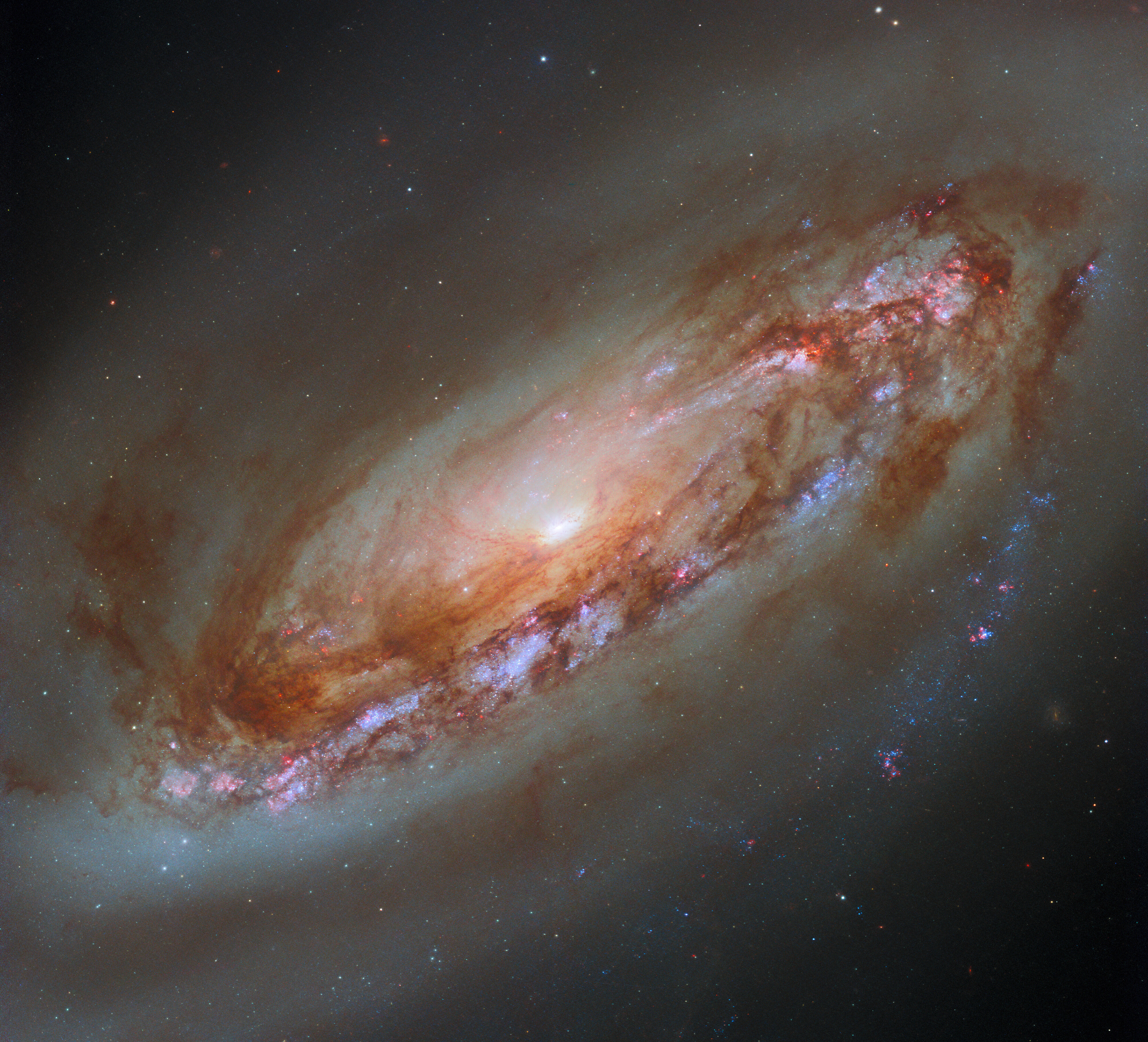

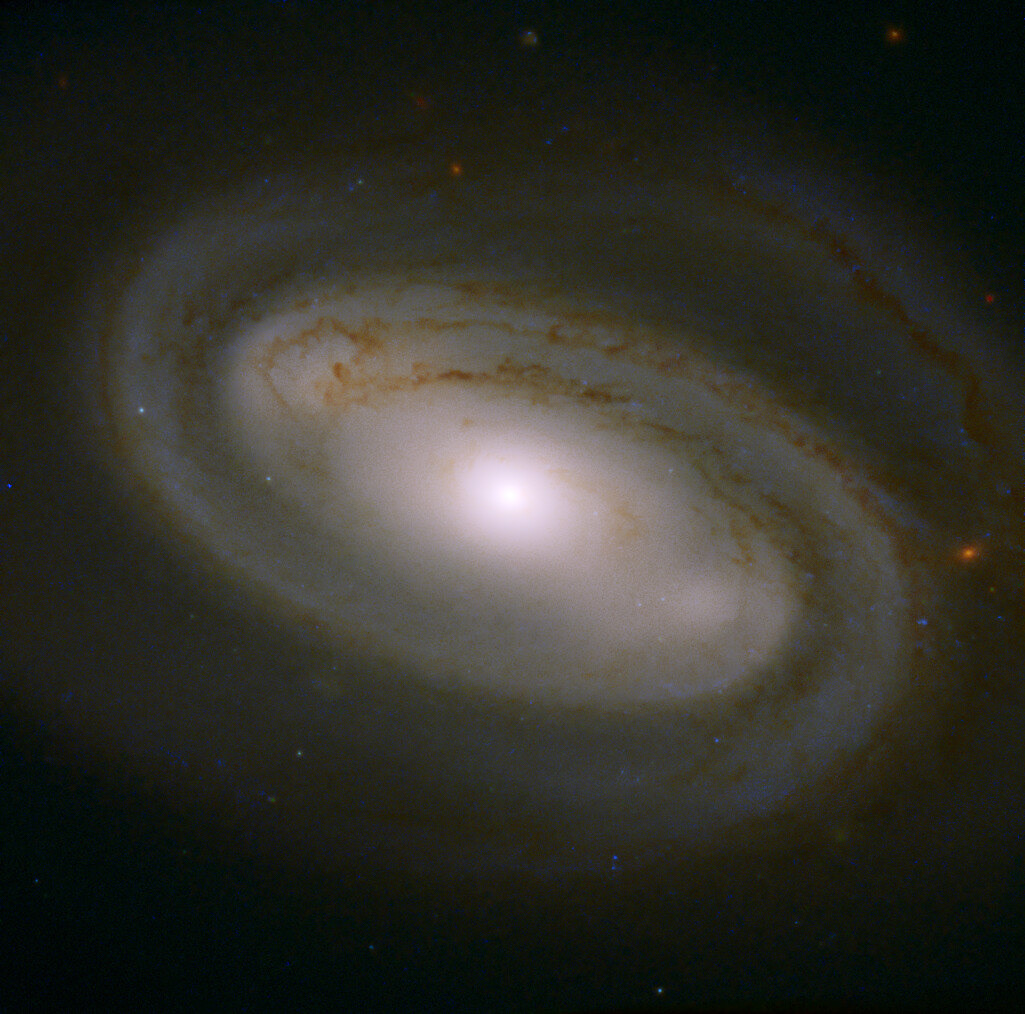

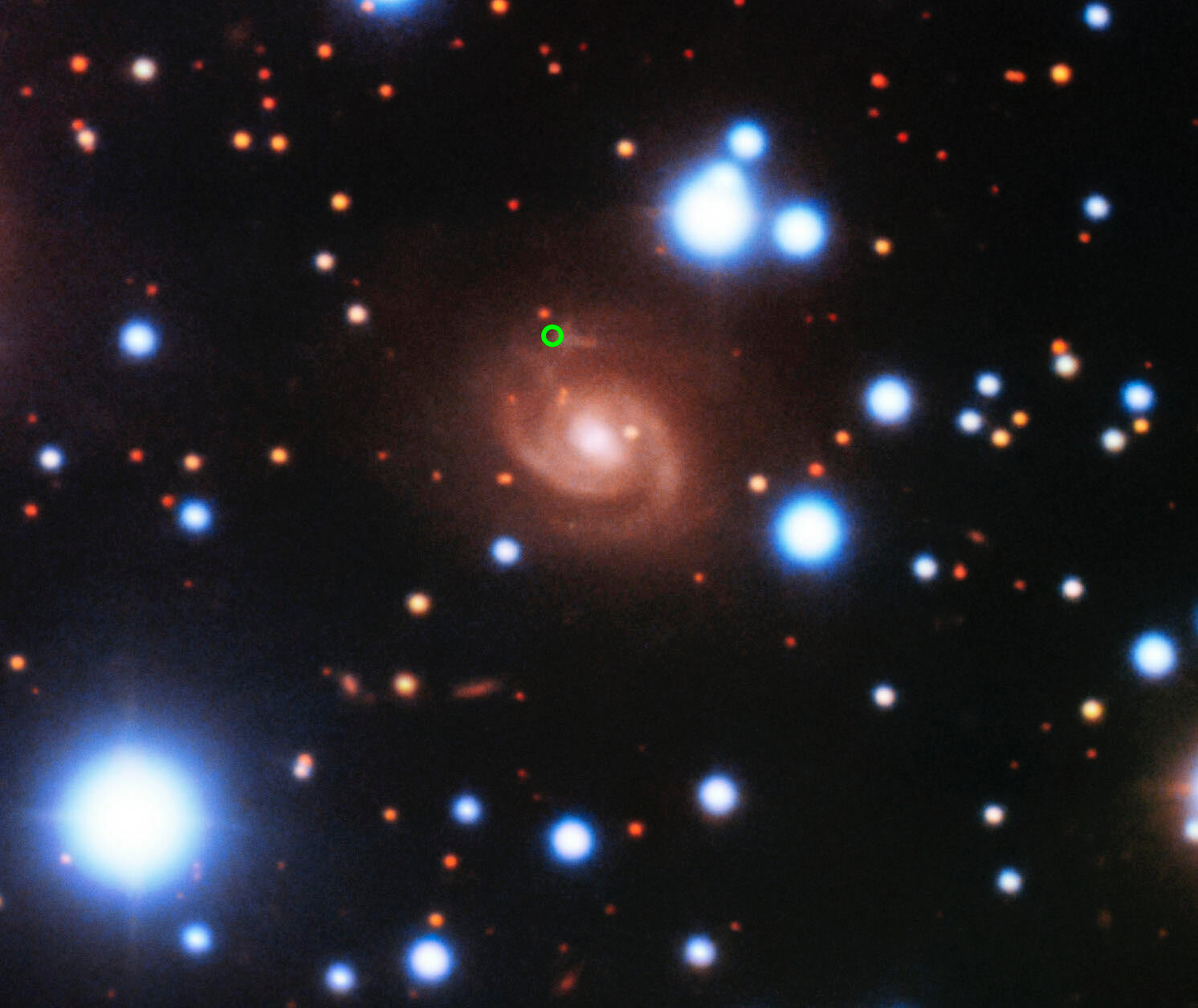

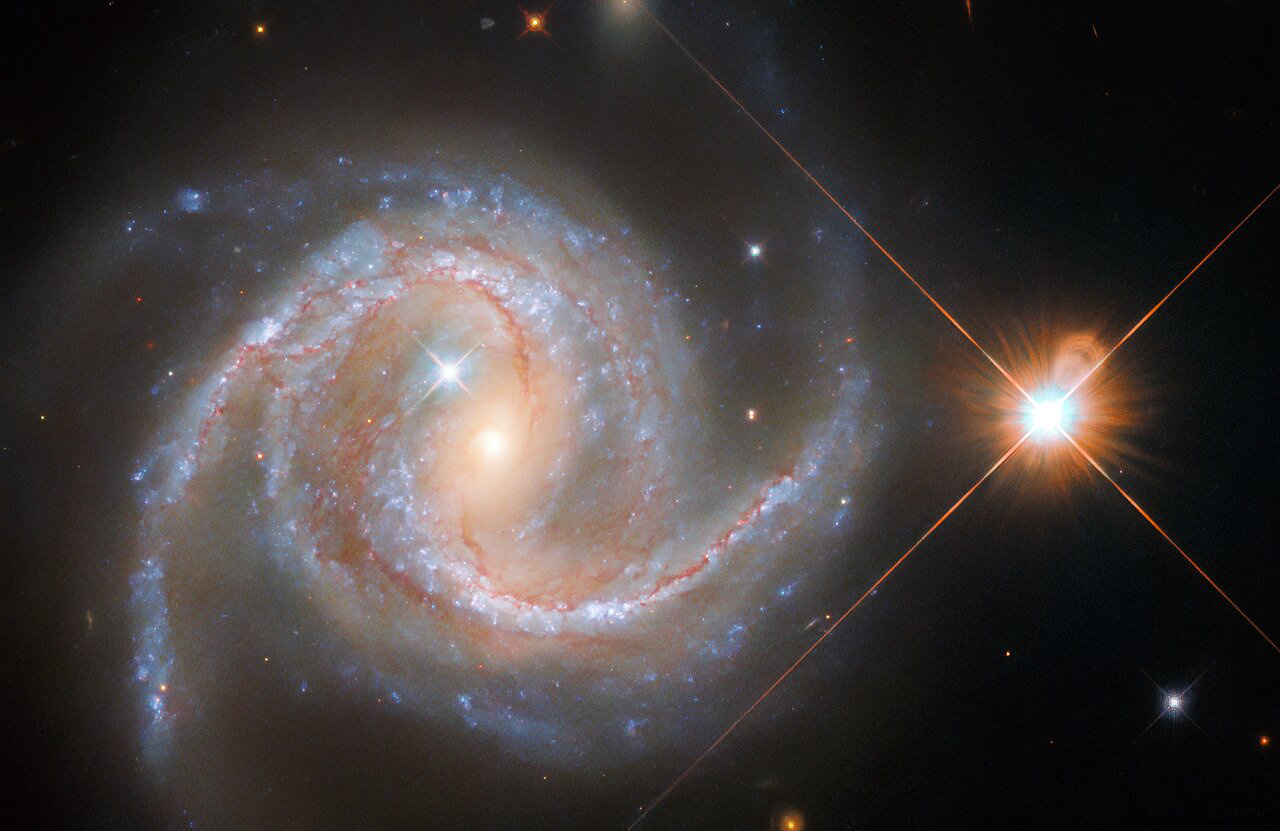

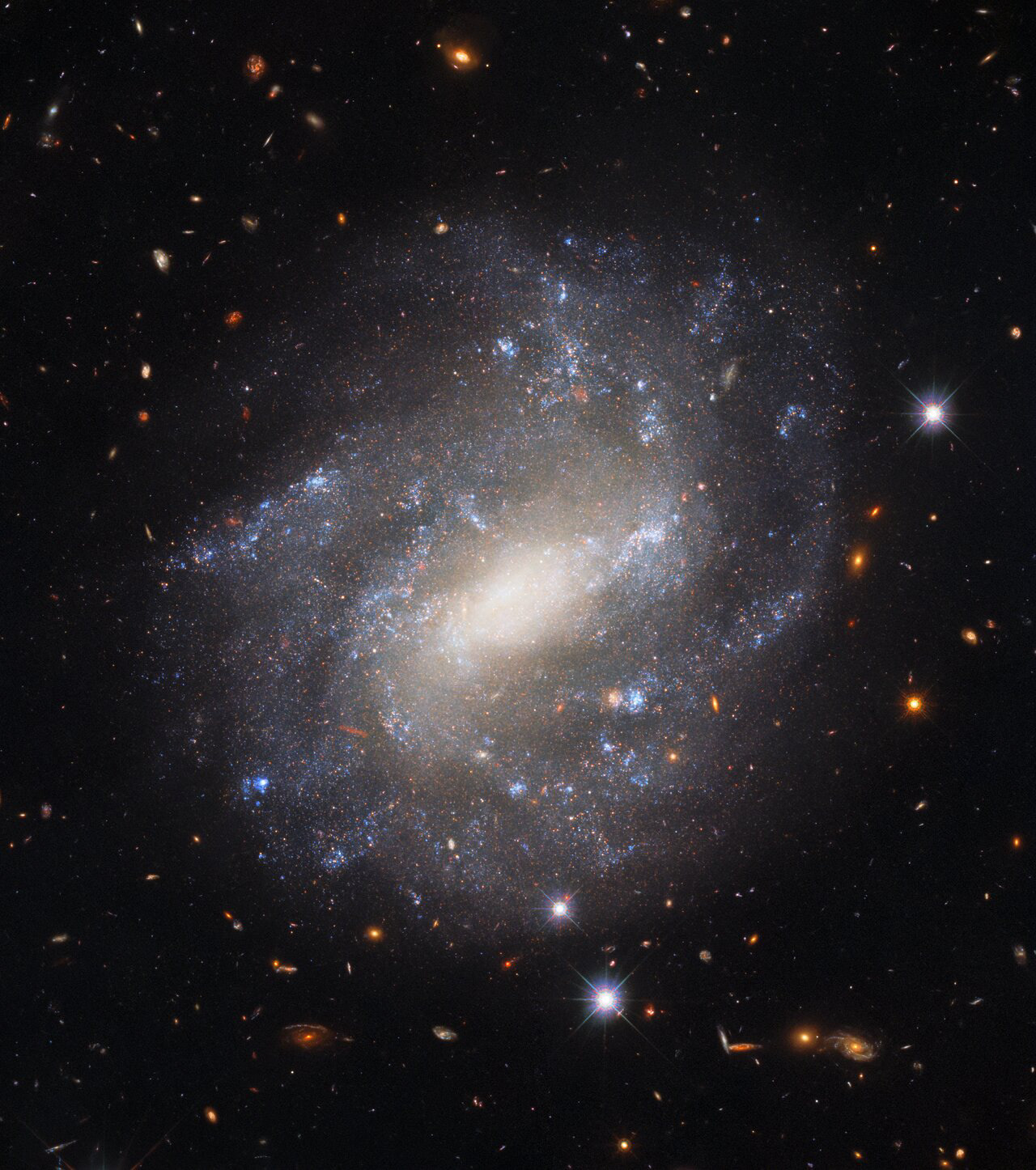

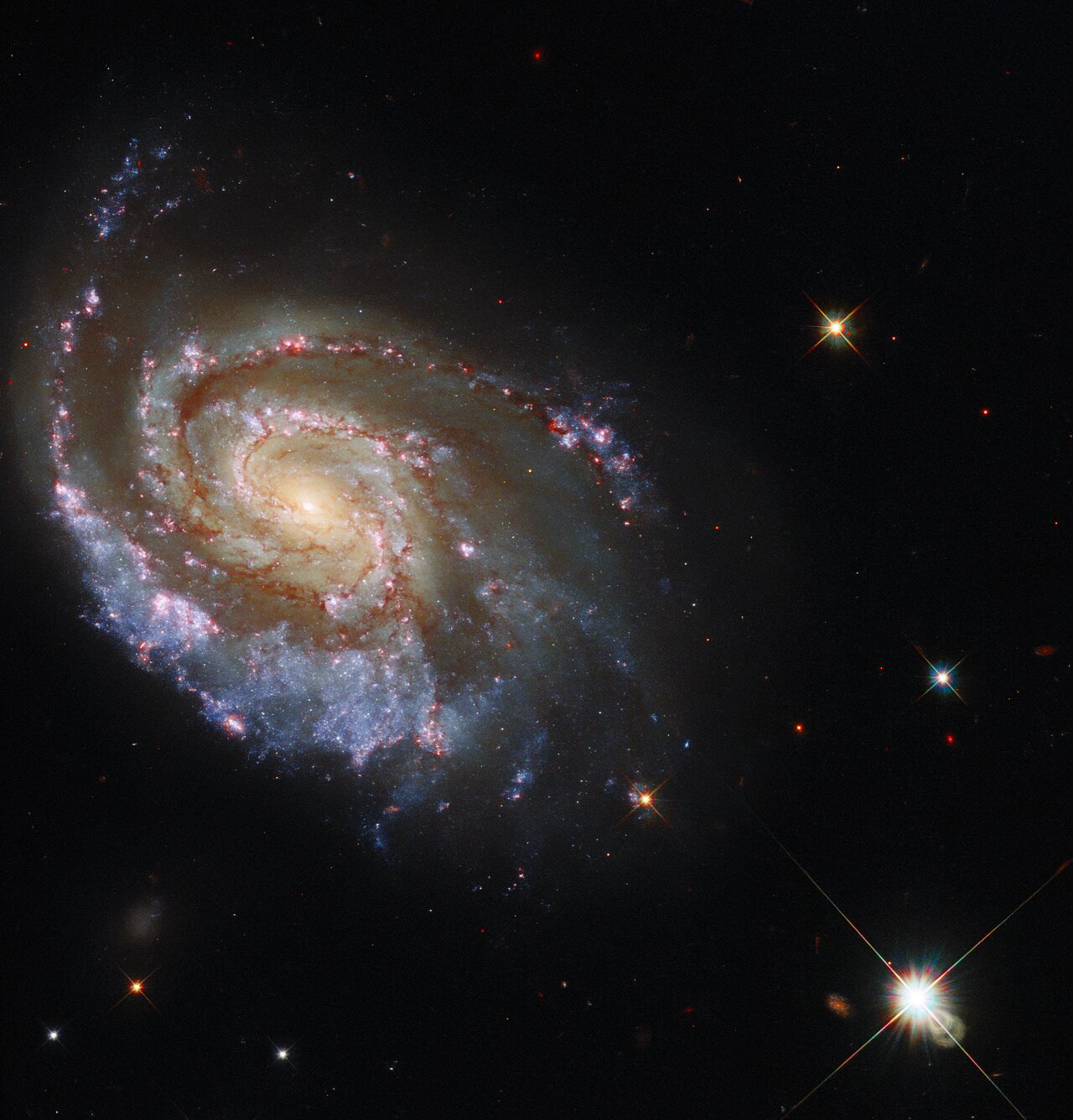

This stunning image by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope features the spiral galaxy NGC 5643 in the constellation of Lupus (The Wolf). Looking this good isn’t easy; thirty different exposures, for a total of 9 hours observation time, together with the high resolution and clarity of Hubble, were needed to produce an image of such high level of detail and of beauty. NGC 5643 is about 60 million light-years away from Earth and has been the host of a recent supernova event (not visible in this latest image). This supernova (2017cbv) was a specific type in which a white dwarf steals so much mass from a companion star that it becomes unstable and explodes. The explosion releases significant amounts of energy and lights up that part of the galaxy. The observation was proposed by Adam Riess, who was awarded a Nobel Laureate in physics 2011 for his contributions to the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the Universe, alongside Saul Perlmutter and Brian Schmidt. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Riess et al. Acknowledgement: Mahdi Zamani

![A portion of the open cluster NGC 6530 appears as a roiling wall of smoke studded with stars in this image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. NGC 6530 is a collection of several thousand stars lying around 4350 light-years from Earth in the constellation Sagittarius. The cluster is set within the larger Lagoon Nebula, a gigantic interstellar cloud of gas and dust. It is the nebula that gives this image its distinctly smokey appearance; clouds of interstellar gas and dust stretch from one side of this image to the other. Astronomers investigated NGC 6530 using Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Planetary Camera 2. They scoured the region in the hope of finding new examples of proplyds, a particular class of illuminated protoplanetary discs surrounding newborn stars. The vast majority of proplyds have been found in only one region, the nearby Orion Nebula. This makes understanding their origin and lifetimes in other astronomical environments challenging. Hubble’s ability to observe at infrared wavelengths — particularly with Wide Field Camera 3— have made it an indispensable tool for understanding starbirth and the origin of exoplanetary systems. In particular, Hubble was crucial to investigations of the proplyds around newly born stars in the Orion Nebula. The new NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope’s unprecedented observational capabilities at infrared wavelengths will complement Hubble observations by allowing astronomers to peer through the dusty envelopes around newly born stars and investigate the faintest, earliest stages of starbirth. [Image description: Clouds of gas cover the entire view, in a variety of bold colours. In the centre the gas is brighter and very textured, resembling dense smoke. Around the edges it is more sparse and faint. Several small, bright blue stars are scattered over the nebula.] Links Video of A Cosmic Smokescreen Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, ESO, O. De Marco Acknowledgement: M. H. Özsaraç](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

A portion of the open cluster NGC 6530 appears as a roiling wall of smoke studded with stars in this image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. NGC 6530 is a collection of several thousand stars lying around 4350 light-years from Earth in the constellation Sagittarius. The cluster is set within the larger Lagoon Nebula, a gigantic interstellar cloud of gas and dust. It is the nebula that gives this image its distinctly smokey appearance; clouds of interstellar gas and dust stretch from one side of this image to the other. Astronomers investigated NGC 6530 using Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Planetary Camera 2. They scoured the region in the hope of finding new examples of proplyds, a particular class of illuminated protoplanetary discs surrounding newborn stars. The vast majority of proplyds have been found in only one region, the nearby Orion Nebula. This makes understanding their origin and lifetimes in other astronomical environments challenging. Hubble’s ability to observe at infrared wavelengths — particularly with Wide Field Camera 3— have made it an indispensable tool for understanding starbirth and the origin of exoplanetary systems. In particular, Hubble was crucial to investigations of the proplyds around newly born stars in the Orion Nebula. The new NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope’s unprecedented observational capabilities at infrared wavelengths will complement Hubble observations by allowing astronomers to peer through the dusty envelopes around newly born stars and investigate the faintest, earliest stages of starbirth. [Image description: Clouds of gas cover the entire view, in a variety of bold colours. In the centre the gas is brighter and very textured, resembling dense smoke. Around the edges it is more sparse and faint. Several small, bright blue stars are scattered over the nebula.] Links Video of A Cosmic Smokescreen Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, ESO, O. De Marco Acknowledgement: M. H. Özsaraç

Gemini North Back On Sky With Dazzling Image of Supernova in the Pinwheel Galaxy - Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Image Processing: J. Miller (Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab), M. Rodriguez (Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab), M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab), T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab) & D. de Martin (NSF NOIRLab). Astronomical processing done with DRAGONS 3.1.

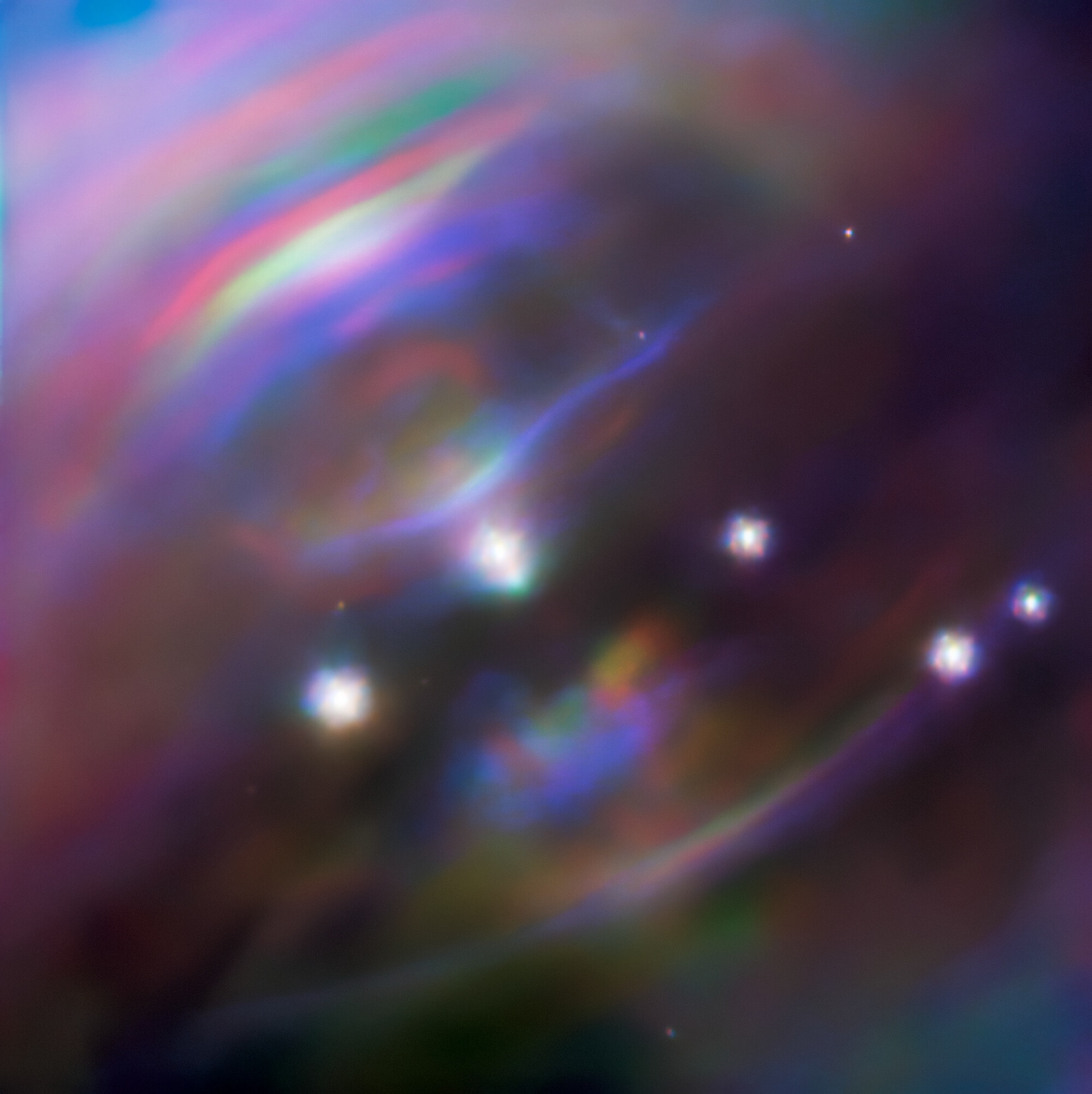

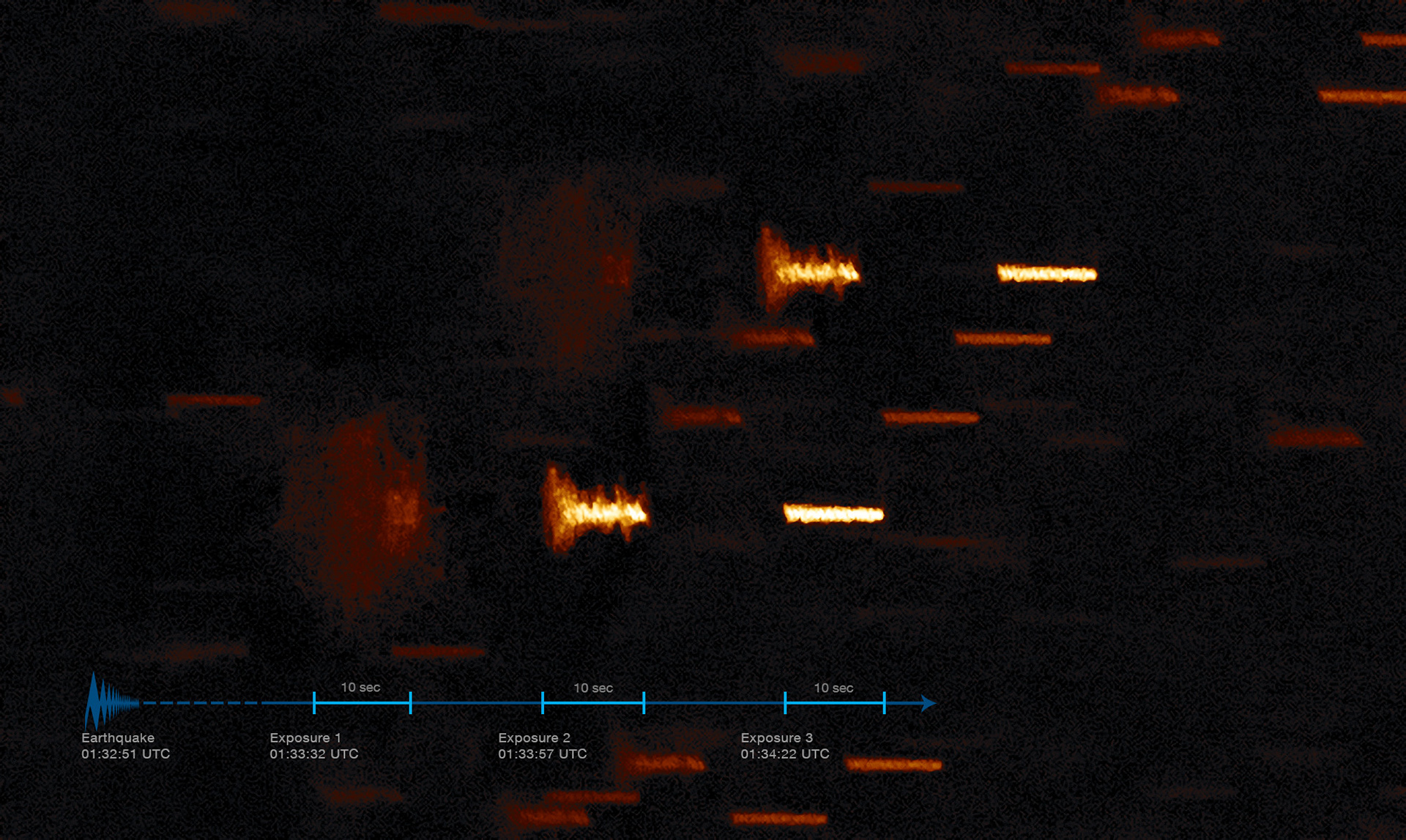

Moving heart of the Crab Nebula / While many other images of the famous Crab Nebula have focused on the filaments in the outer part of the nebula, this image shows the very heart of the Crab Nebula including the central neutron star — it is the rightmost of the two bright stars near the centre of this image. The rapid motion of the material nearest to the central star is revealed by the subtle rainbow of colours in this time-lapse image, the rainbow effect being due to the movement of material over the time between one image and another. Credit: NASA, ESA

![The scattered stars of the globular cluster NGC 6355 are strewn across this image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. This globular cluster lies less than 50,000 light-years from Earth in the Ophiuchus constellation. NGC 6355 is a galactic globular cluster that resides in our Milky Way galaxy's inner regions. Globular clusters are stable, tightly bound clusters of tens of thousands to millions of stars, and can be found in all types of galaxies. Their dense populations of stars and mutual gravitational attraction give these clusters a roughly spherical shape, with a bright concentration of stars surrounded by an increasingly sparse sprinkling of stars. The dense, bright core of NGC 6355 was picked out in crystal-clear detail by Hubble in this image, and is the crowded area of stars towards the centre of this image. With its vantage point above the distortions of the atmosphere, Hubble has revolutionised the study of globular clusters. It is almost impossible to distinguish the stars in globular clusters from one another with ground-based telescopes, but astronomers have been able to use Hubble to study the constituent stars of globular clusters in detail. This Hubble image of NGC 6355 contains data from both the Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Camera 3. [Image description: A dense collection of stars covers the view. Towards the centre the stars become even more dense in a circular region, and also more blue. Around the edges there are some redder foreground stars, and many small stars in the background.] Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, E. Noyola, R. Cohen](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

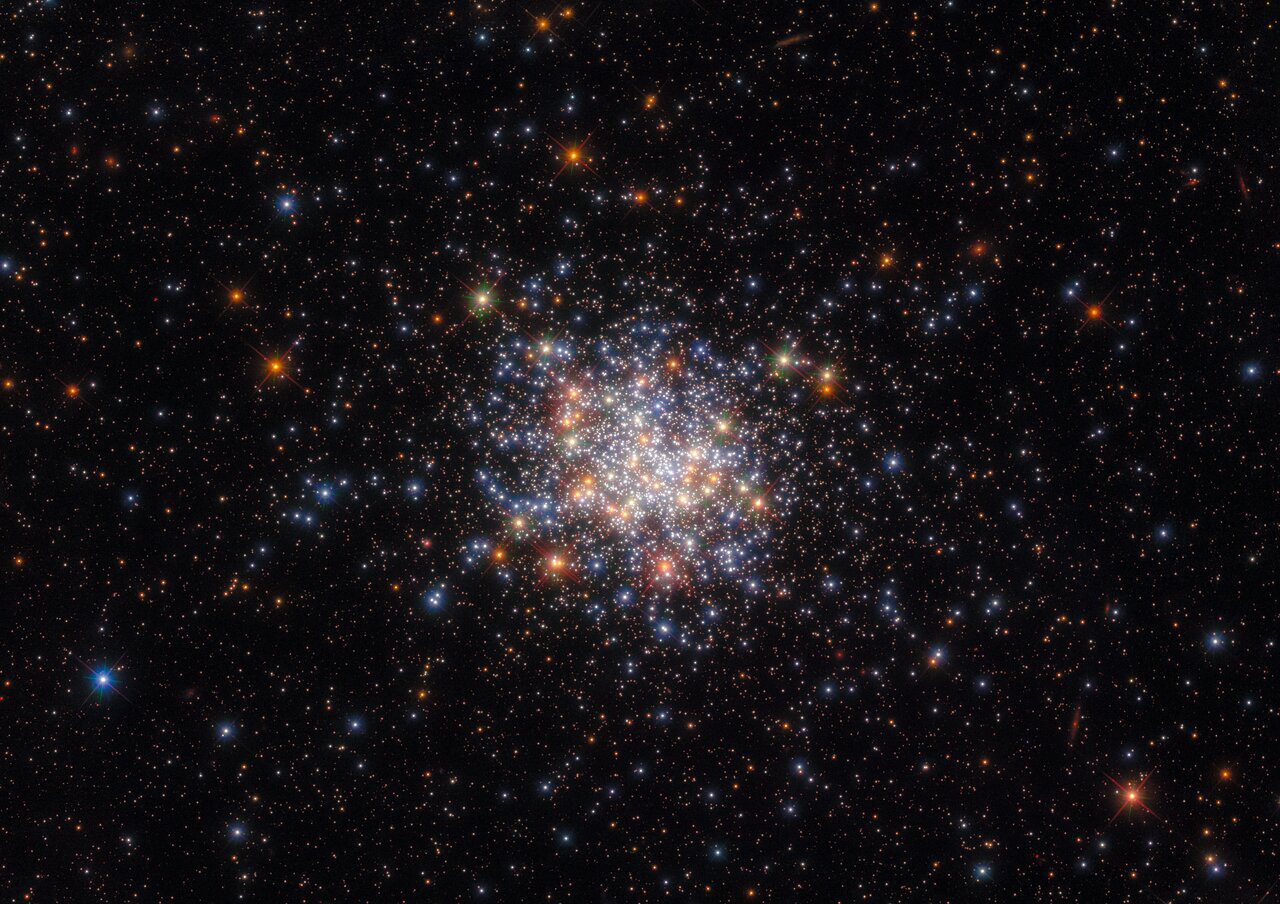

The scattered stars of the globular cluster NGC 6355 are strewn across this image from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. This globular cluster lies less than 50,000 light-years from Earth in the Ophiuchus constellation. NGC 6355 is a galactic globular cluster that resides in our Milky Way galaxy's inner regions. Globular clusters are stable, tightly bound clusters of tens of thousands to millions of stars, and can be found in all types of galaxies. Their dense populations of stars and mutual gravitational attraction give these clusters a roughly spherical shape, with a bright concentration of stars surrounded by an increasingly sparse sprinkling of stars. The dense, bright core of NGC 6355 was picked out in crystal-clear detail by Hubble in this image, and is the crowded area of stars towards the centre of this image. With its vantage point above the distortions of the atmosphere, Hubble has revolutionised the study of globular clusters. It is almost impossible to distinguish the stars in globular clusters from one another with ground-based telescopes, but astronomers have been able to use Hubble to study the constituent stars of globular clusters in detail. This Hubble image of NGC 6355 contains data from both the Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Camera 3. [Image description: A dense collection of stars covers the view. Towards the centre the stars become even more dense in a circular region, and also more blue. Around the edges there are some redder foreground stars, and many small stars in the background.] Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, E. Noyola, R. Cohen

Eagle Nebula (Hubble35 version) - Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, K. Noll

![This image from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope depicts IC 1623, an entwined pair of interacting galaxies which lies around 270 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Cetus. The two galaxies in IC 1623 are plunging headlong into one another in a process known as a galaxy merger. Their collision has ignited a frenzied spate of star formation known as a starburst, creating new stars at a rate more than twenty times that of the Milky Way galaxy. This interacting galaxy system is particularly bright at infrared wavelengths, making it a perfect proving ground for Webb’s ability to study luminous galaxies. A team of astronomers captured IC 1623 across the infrared portions of the electromagnetic spectrum using a trio of Webb’s cutting-edge scientific instruments: MIRI, NIRSpec, and NIRCam. In so doing, they provided an abundance of data that will allow the astronomical community at large to fully explore how Webb’s unprecedented capabilities will help to unravel the complex interactions in galactic ecosystems. These observations are also accompanied by data from other observatories, including the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, and will help set the stage for future observations of galactic systems with Webb. The merger of these two galaxies has long been of interest to astronomers, and has previously been imaged by Hubble and by other space telescopes. The ongoing, extreme starburst causes intense infrared emission, and the merging galaxies may well be in the process of forming a supermassive black hole. A thick band of dust has blocked these valuable insights from the view of telescopes like Hubble. However, Webb’s infrared sensitivity and its impressive resolution at those wavelengths allows it to see past the dust and has resulted in the spectacular image above, a combination of MIRI and NIRCam imagery. The luminous core of the galaxy merger turns out to be both very bright and highly compact, so much so that Webb’s diffraction spikes appear atop the galaxy in this image. The 8-pronged, snowflake-like diffraction spikes are created by the interaction of starlight with the physical structure of the telescope. The spiky quality of Webb’s observations is particularly noticeable in images containing bright stars, such as Webb’s first deep field image. MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a consortium of nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with JPL and the University of Arizona. NIRSpec was built for the European Space Agency (ESA) by a consortium of European companies led by Airbus Defence and Space (ADS) with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center providing its detector and micro-shutter subsystems. Results based on this observation of IC 1623 have been published in the Astrophysical Journal. [Image description: The two galaxies swirl into a single chaotic object in the centre. Long, blue spiral arms stretch vertically, faint at the edges. Hot gas spreads horizontally over that, mainly bright red with many small gold spots of star formation. The core of the merging galaxies is very bright and radiates eight large, golden diffraction spikes. The background is black, with many tiny galaxies in orange and blue.] Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, L. Armus & A. Evans Acknowledgement: R. Colombari](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

This image from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope depicts IC 1623, an entwined pair of interacting galaxies which lies around 270 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Cetus. The two galaxies in IC 1623 are plunging headlong into one another in a process known as a galaxy merger. Their collision has ignited a frenzied spate of star formation known as a starburst, creating new stars at a rate more than twenty times that of the Milky Way galaxy. This interacting galaxy system is particularly bright at infrared wavelengths, making it a perfect proving ground for Webb’s ability to study luminous galaxies. A team of astronomers captured IC 1623 across the infrared portions of the electromagnetic spectrum using a trio of Webb’s cutting-edge scientific instruments: MIRI, NIRSpec, and NIRCam. In so doing, they provided an abundance of data that will allow the astronomical community at large to fully explore how Webb’s unprecedented capabilities will help to unravel the complex interactions in galactic ecosystems. These observations are also accompanied by data from other observatories, including the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, and will help set the stage for future observations of galactic systems with Webb. The merger of these two galaxies has long been of interest to astronomers, and has previously been imaged by Hubble and by other space telescopes. The ongoing, extreme starburst causes intense infrared emission, and the merging galaxies may well be in the process of forming a supermassive black hole. A thick band of dust has blocked these valuable insights from the view of telescopes like Hubble. However, Webb’s infrared sensitivity and its impressive resolution at those wavelengths allows it to see past the dust and has resulted in the spectacular image above, a combination of MIRI and NIRCam imagery. The luminous core of the galaxy merger turns out to be both very bright and highly compact, so much so that Webb’s diffraction spikes appear atop the galaxy in this image. The 8-pronged, snowflake-like diffraction spikes are created by the interaction of starlight with the physical structure of the telescope. The spiky quality of Webb’s observations is particularly noticeable in images containing bright stars, such as Webb’s first deep field image. MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a consortium of nationally funded European Institutes (The MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with JPL and the University of Arizona. NIRSpec was built for the European Space Agency (ESA) by a consortium of European companies led by Airbus Defence and Space (ADS) with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center providing its detector and micro-shutter subsystems. Results based on this observation of IC 1623 have been published in the Astrophysical Journal. [Image description: The two galaxies swirl into a single chaotic object in the centre. Long, blue spiral arms stretch vertically, faint at the edges. Hot gas spreads horizontally over that, mainly bright red with many small gold spots of star formation. The core of the merging galaxies is very bright and radiates eight large, golden diffraction spikes. The background is black, with many tiny galaxies in orange and blue.] Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, L. Armus & A. Evans Acknowledgement: R. Colombari

This image of the spiral galaxy Messier 106, or NGC 4258, was taken with the Nicholas U. Mayall 4-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. A popular target for amateur astronomers, Messier 106 can also be spotted with a small telescope in the constellation Canes Venatici. This view captures the entire galaxy, detailing the glowing spiral arms, wisps of gas, and dust lanes at the center of Messier 106 as well as the leisurely twisting bands of stars at the galaxy’s outer edges. Two dwarf galaxies also appear in the image: NGC 4248 in the lower right and UGC 7358 in the lower left. Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgment: PI: M.T. Patterson (New Mexico State University) Image processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), M. Zamani & D. de Martin

![This image is dominated by NGC 7469, a luminous, face-on spiral galaxy approximately 90 000 light-years in diameter that lies roughly 220 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus. Its companion galaxy IC 5283 is partly visible in the lower left portion of this image. This spiral galaxy has recently been studied as part of the Great Observatories All-sky LIRGs Survey (GOALS) Early Release Science program with the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, which aims to study the physics of star formation, black hole growth, and feedback in four nearby, merging luminous infrared galaxies. Other galaxies studied as part of the survey include previous ESA/Webb Pictures of the Month II ZW 096 and IC 1623. NGC 7469 is home to an active galactic nucleus (AGN), which is an extremely bright central region that is dominated by the light emitted by dust and gas as it falls into the galaxy’s central black hole. This galaxy provides astronomers with the unique opportunity to study the relationship between AGNs and starburst activity because this particular object hosts an AGN that is surrounded by a starburst ring at a distance of a mere 1500 light-years. While NGC 7469 is one of the best studied AGNs in the sky, the compact nature of this system and the presence of a great deal of dust have made it difficult for scientists to achieve both the resolution and sensitivity needed to study this relationship in the infrared. Now, with Webb, astronomers can explore the galaxy’s starburst ring, the central AGN, and the gas and dust in between. Using Webb’s MIRI, NIRCam and NIRspec instruments to obtain images and spectra of NGC 7469 in unprecedented detail, the GOALS team has uncovered a number of details about the object. This includes very young star-forming clusters never seen before, as well as pockets of very warm, turbulent molecular gas, and direct evidence for the destruction of small dust grains within a few hundred light-years of the nucleus — proving that the AGN is impacting the surrounding interstellar medium. Furthermore, highly ionised, diffuse atomic gas seems to be exiting the nucleus at roughly 6.4 million kilometres per hour — part of a galactic outflow that had previously been identified, but is now revealed in stunning detail with Webb. With analysis of the rich Webb datasets still underway, additional secrets of this local AGN and starburst laboratory are sure to be revealed. A prominent feature of this image is the striking six-pointed star that perfectly aligns with the heart of NGC 7469. Unlike the galaxy, this is not a real celestial object, but an imaging artifact known as a diffraction spike, caused by the bright, unresolved AGN. Diffraction spikes are patterns produced as light bends around the sharp edges of a telescope. Webb’s primary mirror is composed of hexagonal segments that each contain edges for light to diffract against, giving six bright spikes. There are also two shorter, fainter spikes, which are created by diffraction from the vertical strut that helps support Webb’s secondary mirror. [Image Description: This image shows a spiral galaxy that is dominated by a bright central region. The galaxy has blue-purple hues with orange-red regions filled with stars. Also visible is large diffraction spike, which appears as a star pattern over the central region of the galaxy. Lots of stars and galaxies fill the background scene.] Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, L. Armus, A. S. Evans](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

This image is dominated by NGC 7469, a luminous, face-on spiral galaxy approximately 90 000 light-years in diameter that lies roughly 220 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus. Its companion galaxy IC 5283 is partly visible in the lower left portion of this image. This spiral galaxy has recently been studied as part of the Great Observatories All-sky LIRGs Survey (GOALS) Early Release Science program with the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope, which aims to study the physics of star formation, black hole growth, and feedback in four nearby, merging luminous infrared galaxies. Other galaxies studied as part of the survey include previous ESA/Webb Pictures of the Month II ZW 096 and IC 1623. NGC 7469 is home to an active galactic nucleus (AGN), which is an extremely bright central region that is dominated by the light emitted by dust and gas as it falls into the galaxy’s central black hole. This galaxy provides astronomers with the unique opportunity to study the relationship between AGNs and starburst activity because this particular object hosts an AGN that is surrounded by a starburst ring at a distance of a mere 1500 light-years. While NGC 7469 is one of the best studied AGNs in the sky, the compact nature of this system and the presence of a great deal of dust have made it difficult for scientists to achieve both the resolution and sensitivity needed to study this relationship in the infrared. Now, with Webb, astronomers can explore the galaxy’s starburst ring, the central AGN, and the gas and dust in between. Using Webb’s MIRI, NIRCam and NIRspec instruments to obtain images and spectra of NGC 7469 in unprecedented detail, the GOALS team has uncovered a number of details about the object. This includes very young star-forming clusters never seen before, as well as pockets of very warm, turbulent molecular gas, and direct evidence for the destruction of small dust grains within a few hundred light-years of the nucleus — proving that the AGN is impacting the surrounding interstellar medium. Furthermore, highly ionised, diffuse atomic gas seems to be exiting the nucleus at roughly 6.4 million kilometres per hour — part of a galactic outflow that had previously been identified, but is now revealed in stunning detail with Webb. With analysis of the rich Webb datasets still underway, additional secrets of this local AGN and starburst laboratory are sure to be revealed. A prominent feature of this image is the striking six-pointed star that perfectly aligns with the heart of NGC 7469. Unlike the galaxy, this is not a real celestial object, but an imaging artifact known as a diffraction spike, caused by the bright, unresolved AGN. Diffraction spikes are patterns produced as light bends around the sharp edges of a telescope. Webb’s primary mirror is composed of hexagonal segments that each contain edges for light to diffract against, giving six bright spikes. There are also two shorter, fainter spikes, which are created by diffraction from the vertical strut that helps support Webb’s secondary mirror. [Image Description: This image shows a spiral galaxy that is dominated by a bright central region. The galaxy has blue-purple hues with orange-red regions filled with stars. Also visible is large diffraction spike, which appears as a star pattern over the central region of the galaxy. Lots of stars and galaxies fill the background scene.] Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, L. Armus, A. S. Evans

The emission nebula Sh2-54 glows brightly in this image from the SMARTS 0.9-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Gathering the fine details of this particular image required almost twenty minutes of observations and three different wavelength filters. Situated within the constellation of Serpens (The Serpent), Sh2-54 forms part of a much wider nebulosity which includes the famous Eagle Nebula. Serpens is a unique constellation, the only one of the official 88 used today that is split into two unconnected parts: Serpens Caput — the Serpent’s Head — and Serpens Cauda — The Serpent’s Tail. Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgment: Image processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

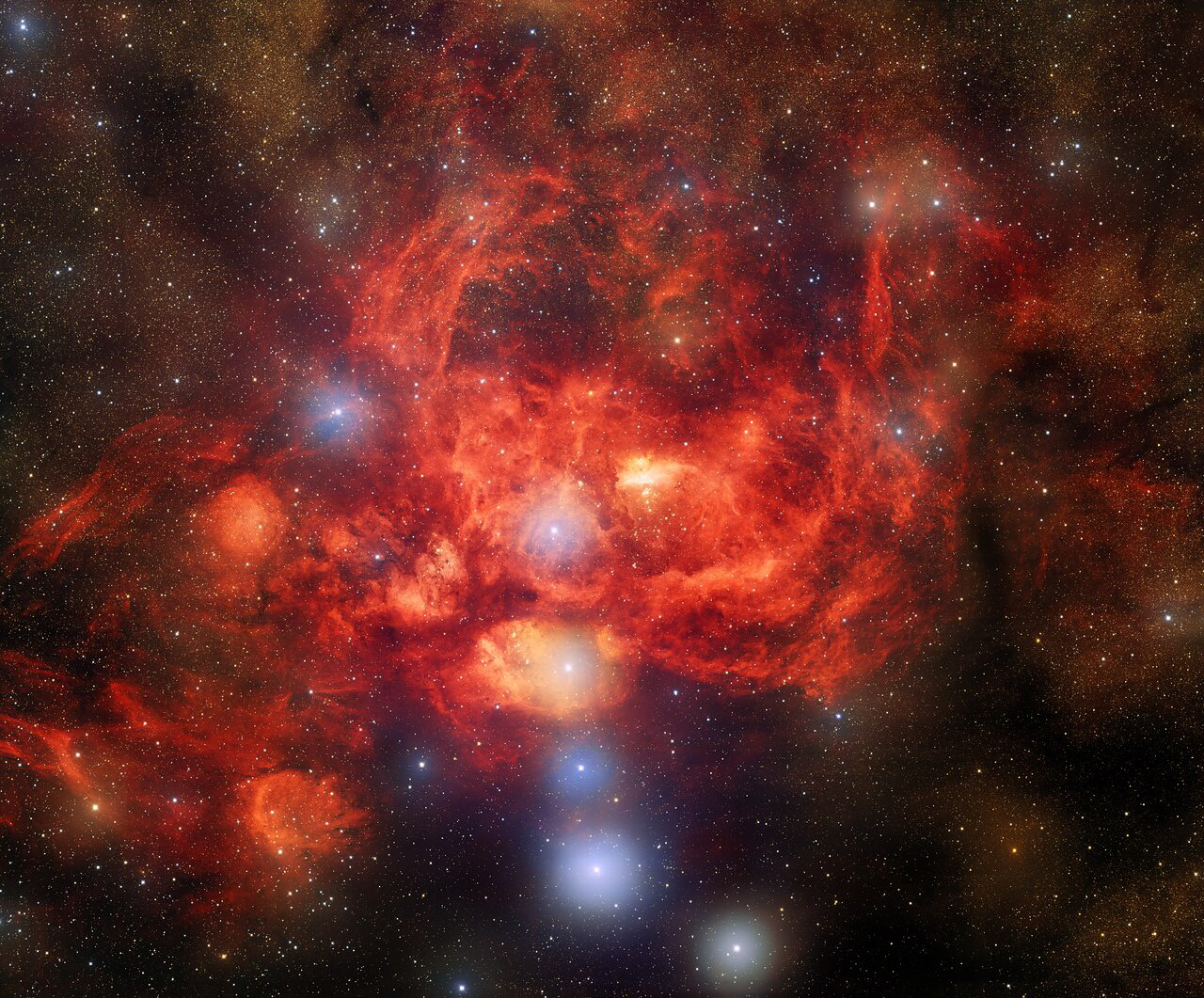

This image, taken by astronomers using the US Department of Energy-fabricated Dark Energy Camera on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab, captures the star-forming nebula NGC 6357, which is located 8000 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Scorpius. This image reveals bright, young stars surrounded by billowing clouds of dust and gas inside NGC 6357, which is also known as the Lobster Nebula. Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF’s NOIRLab), J. Miller (Gemini Observatory/NSF’s NOIRLab), M. Zamani & D. de Martin (NSF’s NOIRLab)

This peculiar portrait from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope showcases NGC 1999, a reflection nebula in the constellation Orion. NGC 1999 is around 1350 light-years from Earth and lies near to the Orion Nebula, the closest region of massive star formation to Earth. NGC 1999 itself is a relic of recent star formation — it is composed of detritus left over from the formation of a newborn star. Just like fog curling around a street lamp, reflection nebulae like NGC 1999 only shine because of the light from an embedded source. In the case of NGC 1999, this source is the aforementioned newborn star V380 Orionis which is visible at the centre of this image. The most notable aspect of NGC 1999’s appearance, however, is the conspicuous hole in its centre, which resembles an inky-black keyhole of cosmic proportions. This image was created from archival Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 observations that date from shortly after Servicing Mission 3A in 1999. At the time, astronomers believed that the dark patch in NGC 1999 was something called a Bok globule — a dense, cold cloud of gas, molecules, and cosmic dust that blots out background light. However, follow-up observations using a collection of telescopes including ESA’s Herschel Space Observatory revealed that the dark patch is actually an empty region of space. The origin of this unexplained rift in the heart of NGC 1999 remains unknown. Links Video of Cosmic Keyhole Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, ESO, K. Noll

KPNO captures irregular starburst galaxy IC 10 in glorious detail This striking image from NOIRLab’s Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO) presents a portrait of the irregular galaxy IC 10, a disorderly starburst galaxy close to the Milky Way. As well as a population of bright young stars, this irregular galaxy harbors exotic Wolf-Rayet stars and a black hole. IC 10 lies around 2 million light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation of Cassiopeia. Though this distance seems huge, it puts IC 10 in the ever-growing Local Group of galaxies. Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Data obtained and processed by: P. Massey (Lowell Obs.), G. Jacoby, K. Olsen, & C. Smith (NOAO/AURA/NSF) Image processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

![Just in time for the festive season, this new Picture of the Week from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope features a glistening scene in holiday red. This image shows a small region of the well-known nebula Westerhout 5, which lies about 7000 light-years from Earth. Suffused with bright red light, this luminous image hosts a variety of interesting features, including a free-floating Evaporating Gaseous Globule (frEGG). The frEGG in this image is the small tadpole-shaped dark region in the upper centre-left. This buoyant-looking bubble is lumbered with two rather uninspiring names — [KAG2008] globule 13 and J025838.6+604259. FrEGGs are a particular class of Evaporating Gaseous Globules (EGGs). Both frEGGs and EGGs are regions of gas that are sufficiently dense that they photoevaporate less easily than the less compact gas surrounding them. Photoevaporation occurs when gas is ionised and dispersed away by an intense source of radiation — typically young, hot stars releasing vast amounts of ultraviolet light. EGGs were only identified fairly recently, most notably at the tips of the Pillars of Creation, which were captured by Hubble in iconic images released in 1995. FrEGGs were classified even more recently, and are distinguished from EGGs by being detached and having a distinct ‘head-tail’ shape. FrEGGs and EGGs are of particular interest because their density makes it more difficult for intense UV radiation, found in regions rich in young stars, to penetrate them. Their relative opacity means that the gas within them is protected from ionisation and photoevaporation. This is thought to be important for the formation of protostars, and it is predicted that many FrEGGs and EGGs will play host to the birth of new stars. The frEGG in this image is a dark spot in the sea of red light. The red colour is caused by a particular type of light emission known as H-alpha emission. This occurs when a very energetic electron within a hydrogen atom loses a set amount of its energy, causing the electron to become less energetic and this distinctive red light to be released. [Image description: The background is filled with bright orange-red clouds of varying density. Towards the top-left several large, pale blue stars with prominent cross-shaped spikes are scattered. A small, tadpole-shaped dark patch floats near one of these stars. More of the same dark, dense gas fills the lower-right, resembling black smoke. A bright yellow star and a smaller blue star shine in front of this.] Links Video of Festive and Free-Floating Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, R. Sahai](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

Just in time for the festive season, this new Picture of the Week from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope features a glistening scene in holiday red. This image shows a small region of the well-known nebula Westerhout 5, which lies about 7000 light-years from Earth. Suffused with bright red light, this luminous image hosts a variety of interesting features, including a free-floating Evaporating Gaseous Globule (frEGG). The frEGG in this image is the small tadpole-shaped dark region in the upper centre-left. This buoyant-looking bubble is lumbered with two rather uninspiring names — [KAG2008] globule 13 and J025838.6+604259. FrEGGs are a particular class of Evaporating Gaseous Globules (EGGs). Both frEGGs and EGGs are regions of gas that are sufficiently dense that they photoevaporate less easily than the less compact gas surrounding them. Photoevaporation occurs when gas is ionised and dispersed away by an intense source of radiation — typically young, hot stars releasing vast amounts of ultraviolet light. EGGs were only identified fairly recently, most notably at the tips of the Pillars of Creation, which were captured by Hubble in iconic images released in 1995. FrEGGs were classified even more recently, and are distinguished from EGGs by being detached and having a distinct ‘head-tail’ shape. FrEGGs and EGGs are of particular interest because their density makes it more difficult for intense UV radiation, found in regions rich in young stars, to penetrate them. Their relative opacity means that the gas within them is protected from ionisation and photoevaporation. This is thought to be important for the formation of protostars, and it is predicted that many FrEGGs and EGGs will play host to the birth of new stars. The frEGG in this image is a dark spot in the sea of red light. The red colour is caused by a particular type of light emission known as H-alpha emission. This occurs when a very energetic electron within a hydrogen atom loses a set amount of its energy, causing the electron to become less energetic and this distinctive red light to be released. [Image description: The background is filled with bright orange-red clouds of varying density. Towards the top-left several large, pale blue stars with prominent cross-shaped spikes are scattered. A small, tadpole-shaped dark patch floats near one of these stars. More of the same dark, dense gas fills the lower-right, resembling black smoke. A bright yellow star and a smaller blue star shine in front of this.] Links Video of Festive and Free-Floating Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, R. Sahai

This Picture of the Week depicts the open star cluster NGC 330, which lies around 180,000 light-years away inside the Small Magellanic Cloud. The cluster — which is in the constellation Tucana (The Toucan) — contains a multitude of stars, many of which are scattered across this striking image. Pictures of the Week from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope show us something new about the Universe. This image, however, also contains clues about the inner workings of Hubble itself. The criss-cross patterns surrounding the stars in this image — known as diffraction spikes — were created when starlight interacted with the four thin vanes supporting Hubble’s secondary mirror. As star clusters form from a single primordial cloud of gas and dust, all the stars they contain are roughly the same age. This makes them useful natural laboratories for astronomers to learn how stars form and evolve. This image uses observations from Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3, and incorporates data from two very different astronomical investigations. The first aimed to understand why stars in star clusters appear to evolve differently from stars elsewhere, a peculiarity first observed by the Hubble Space Telescope. The second aimed to determine how large stars can be before they become doomed to end their lives in cataclysmic supernova explosions. Links Video of A Scattering of Stars Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, J. Kalirai, A. Milone

Pictured here is the captivating galaxy NGC 2525. Located nearly 70 million light-years from Earth, this galaxy is part of the constellation of Puppis in the southern hemisphere. Together with the Carina and the Vela constellations, it makes up an image of the Argo from ancient greek mythology. Another kind of monster, a supermassive black hole, lurks at the centre of NGC 2525. Nearly every galaxy contains a supermassive black hole, which can range in mass from hundreds of thousands to billions of times the mass of the Sun. Hubble has captured a series of images of NGC2525 as part of one of its major investigations; measuring the expansion rate of the Universe, which can help answer fundamental questions about our Universe’s very nature. ESA/Hubble has now published a unique time-lapse of this galaxy and it’s fading supernova. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Riess and the SH0ES team Acknowledgment: Mahdi Zamani

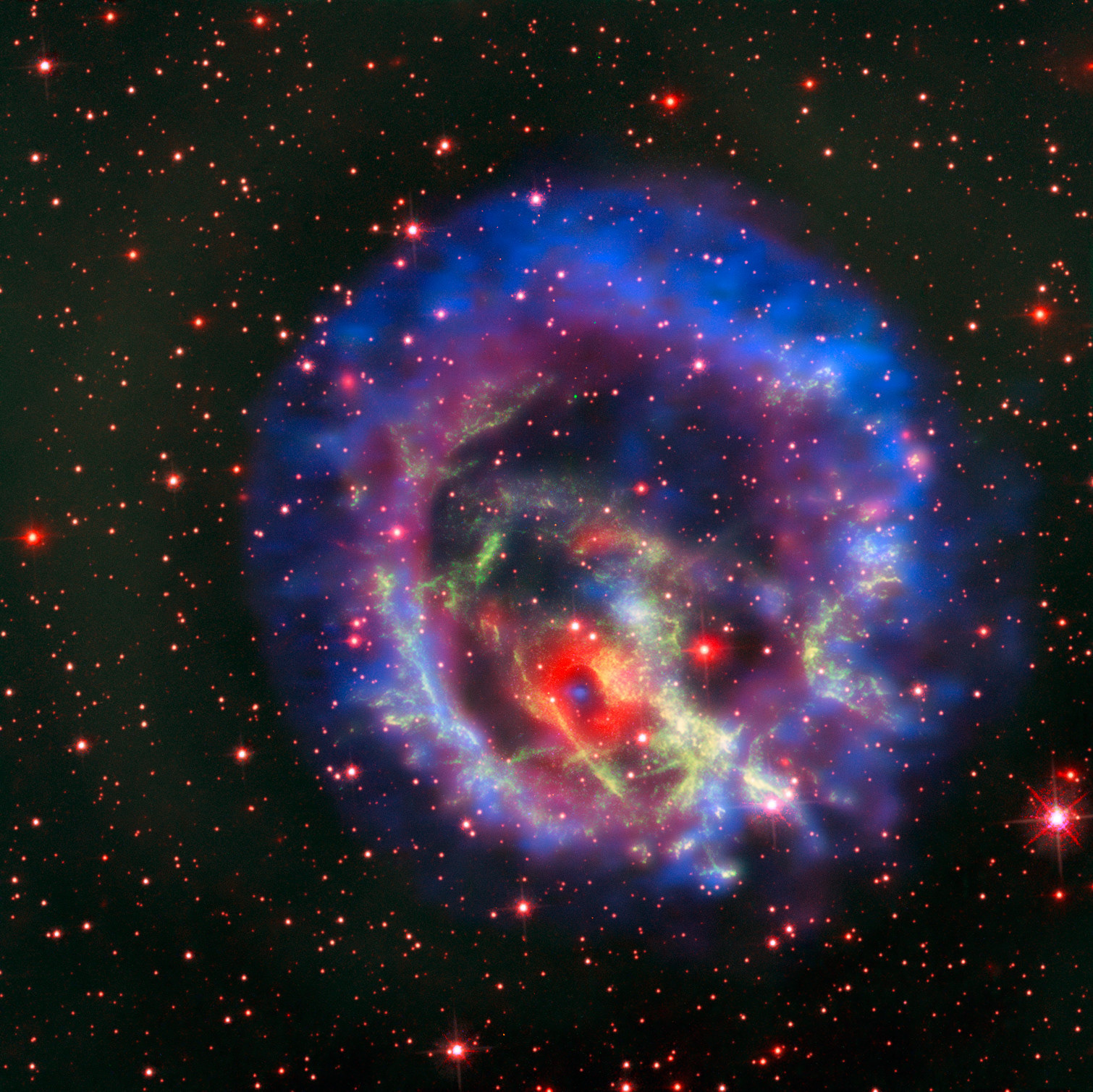

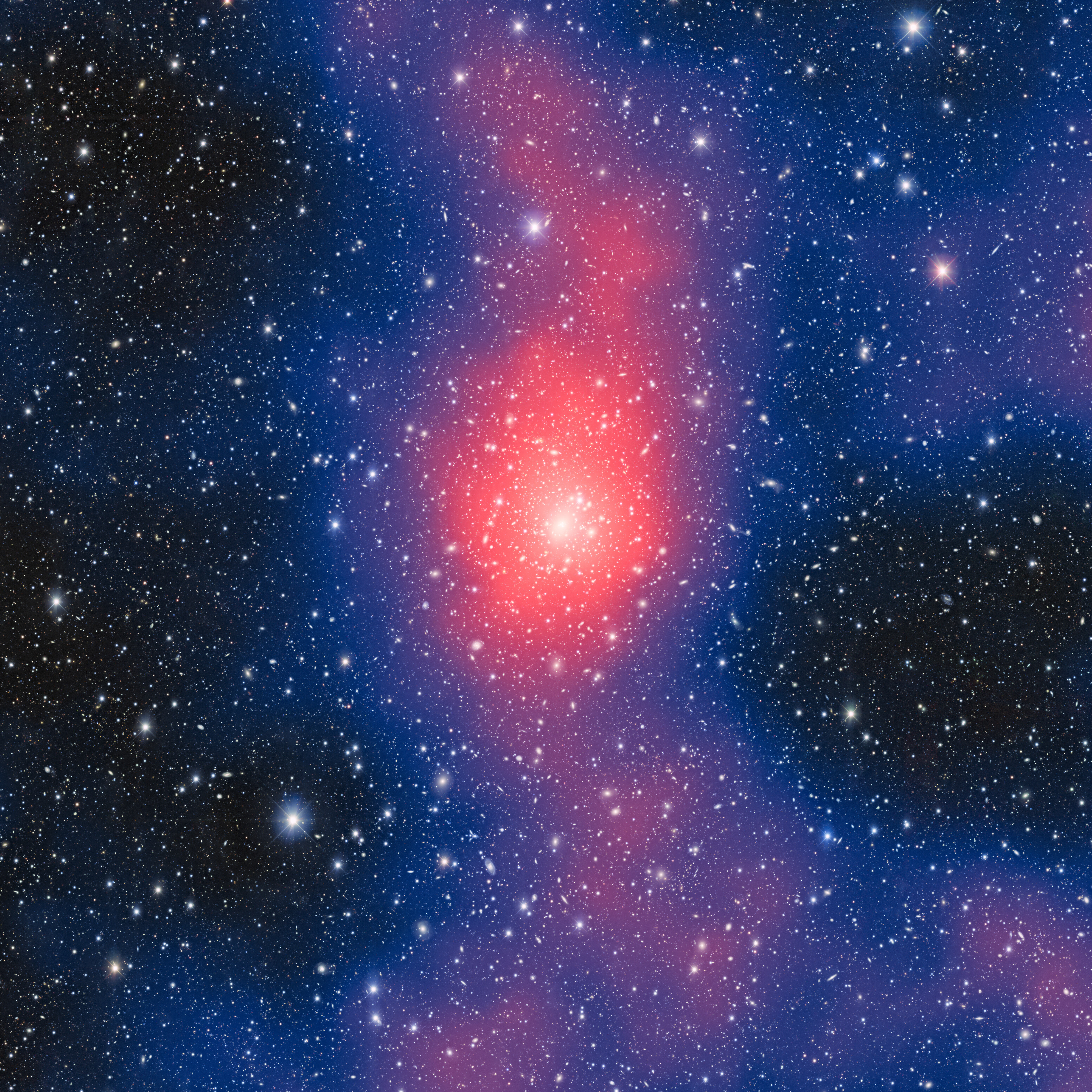

An isolated neutron star in the Small Magellanic Cloud An isolated neutron star in the Small Magellanic Cloud This new picture created from images from telescopes on the ground and in space tells the story of the hunt for an elusive missing object hidden amid a complex tangle of gaseous filaments in one of our nearest neighbouring galaxies, the Small Magellanic Cloud. The reddish background image comes from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and reveals the wisps of gas forming the supernova remnant 1E 0102.2-7219 in green. The red ring with a dark centre is from the MUSE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope and the blue and purple images are from the NASA Chandra X-Ray Observatory. The blue spot at the centre of the red ring is an isolated neutron star with a weak magnetic field, the first identified outside the Milky Way. Credit: ESO/NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)/F. Vogt et al.

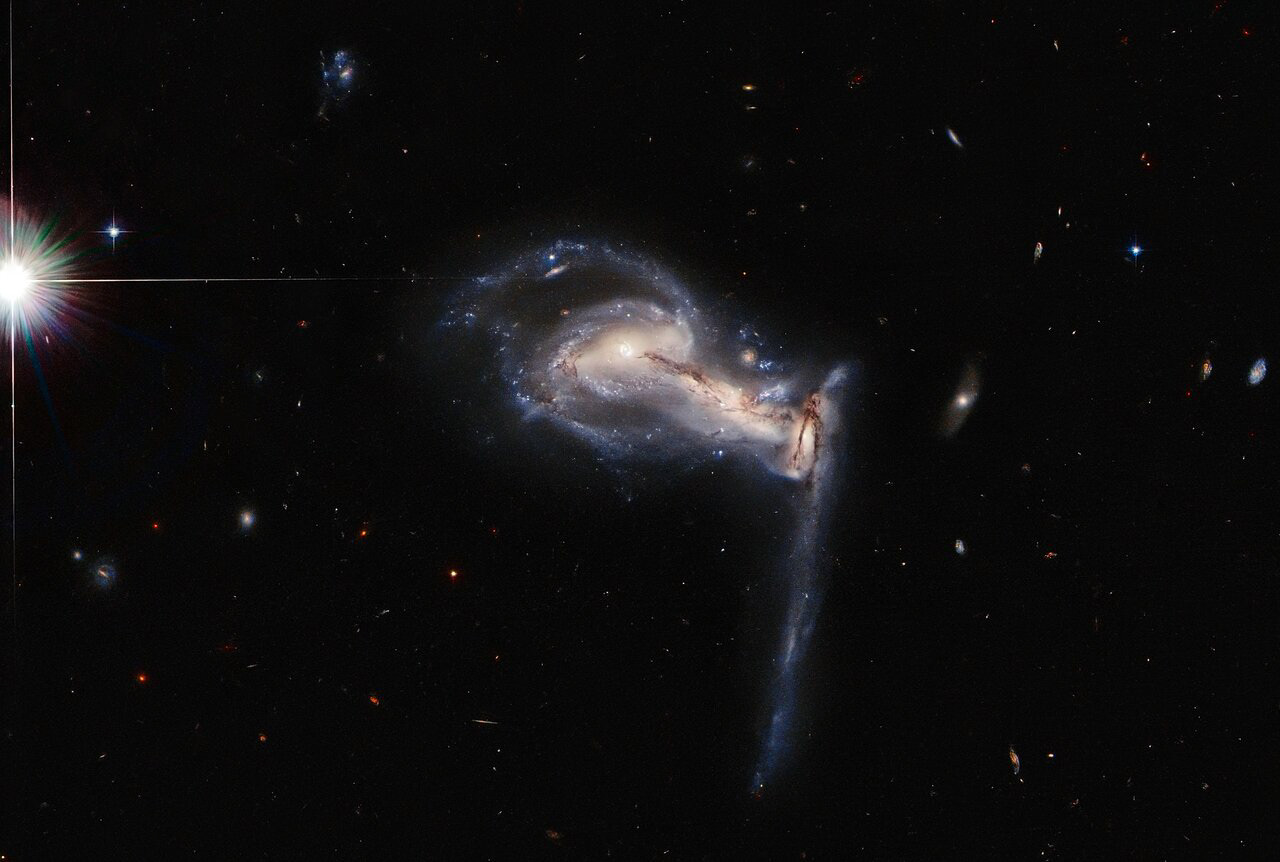

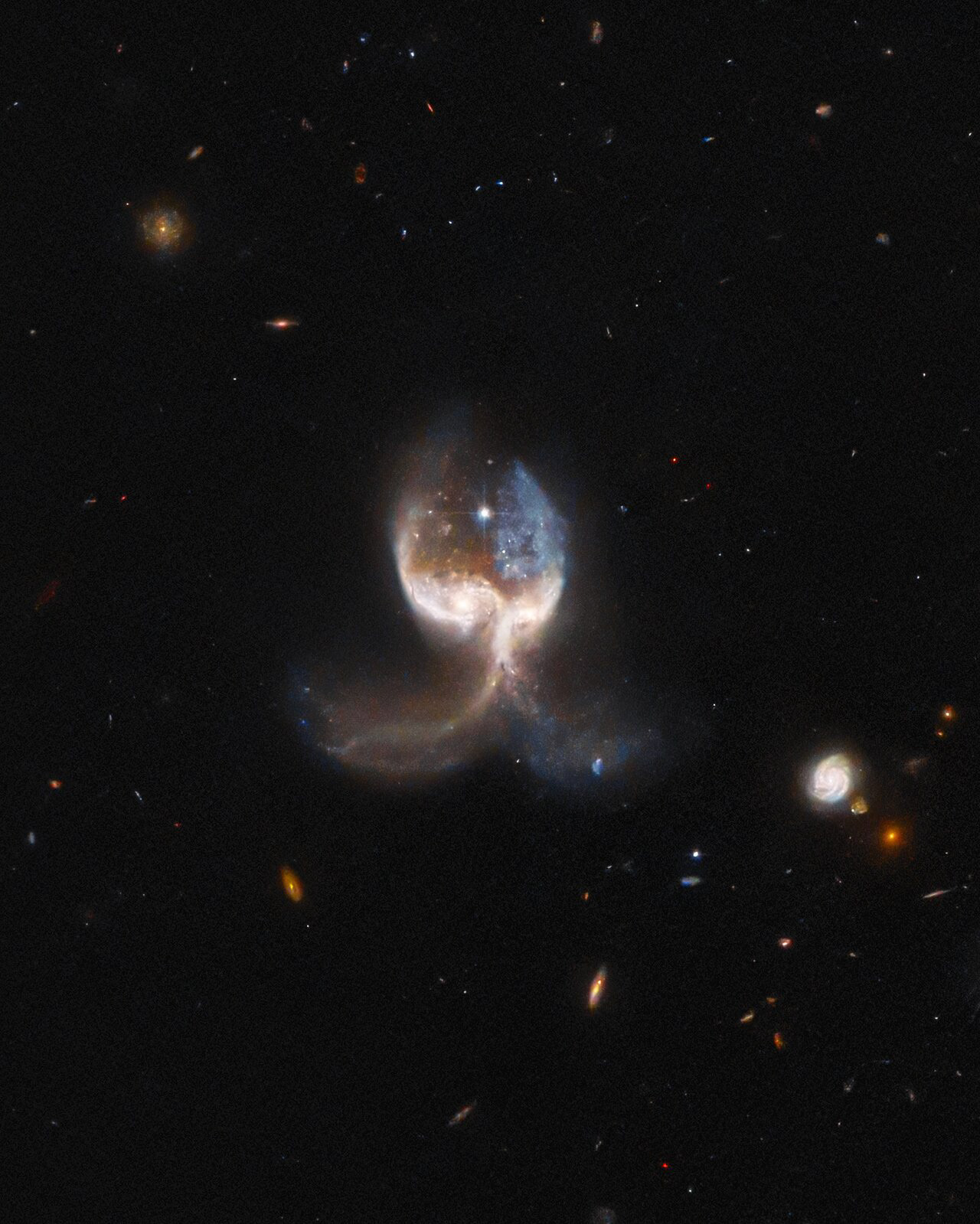

A cataclysmic cosmic collision takes centre stage in this Picture of the Week. The image features the interacting galaxy pair IC 1623, which lies around 275 million light-years away in the constellation Cetus (The Whale). The two galaxies are in the final stages of merging, and astronomers expect a powerful inflow of gas to ignite a frenzied burst of star formation in the resulting compact starburst galaxy. This interacting pair of galaxies is a familiar sight; Hubble captured IC 1623 in 2008 using two filters at optical and infrared wavelengths using the Advanced Camera for Surveys. This new image incorporates new data from Wide Field Camera 3, and combines observations taken in eight filters spanning infrared to ultraviolet wavelengths to reveal the finer details of IC 1623. Future observations of the galaxy pair with the NASA/ESA/CASA James Webb Space Telescope will shed more light on the processes powering extreme star formation in environments such as IC 1623. Links Video of Clash of the Titans Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, R. Chandar

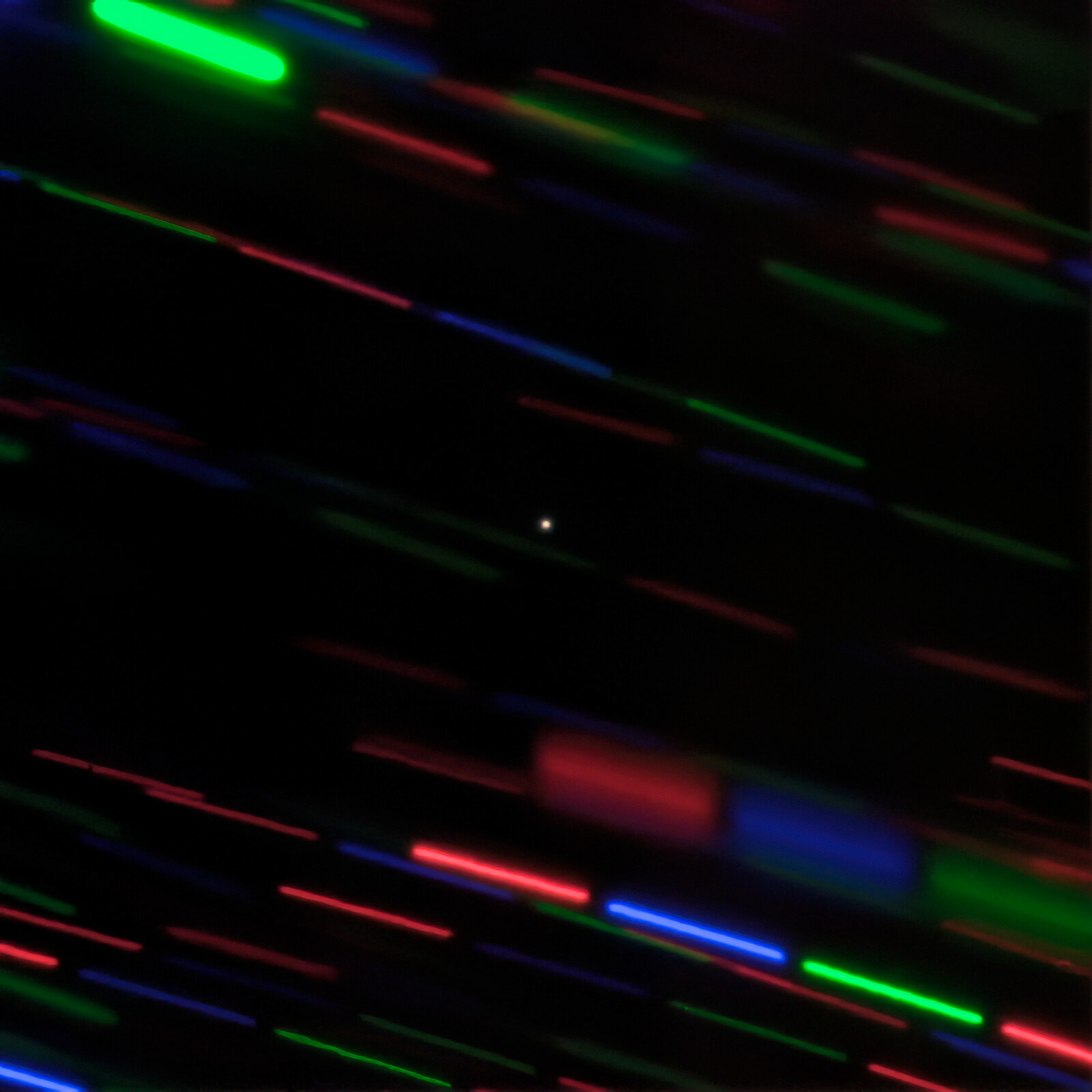

In the heart of the Crab Nebula (Messier 1) a neutron star is rotating 30 times every single second. This pirouetting star, known as the Crab Pulsar, consists purely of neutrons, and has an intense magnetic field which ejects jets of material from its poles at nearly the speed of light. The Crab Pulsar has a mass about one and a half times that of our Sun, yet all this mass is packed into a sphere only 28 km (17 miles) in diameter — roughly the size of Mars’s small moon Phobos. The wispy structures shown in this image are caused by material flowing equatorially outwards from the pulsar and careening into the surrounding nebula. These dynamic features, known as termination shocks, move and change shape as outflow from the puslar ebbs and flows. This changeability is showcased by this composite image, which is a compilation of three Gemini North observations taken over a 5-year period at the same infrared wavelength: observations from October 2009 are shown in blue and observations from December 2014 are shown in red. This color coding of the observations produces a striking rainbow effect highlighting the high speed motion of the termination shocks, which have noticeably changed position between observations. Gemini North on Maunakea, Hawai‘i, is one of the pair of telescopes that make up the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgments: Image processing: Jen Miller (Gemini Observatory/NSF's NOIRLab), Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

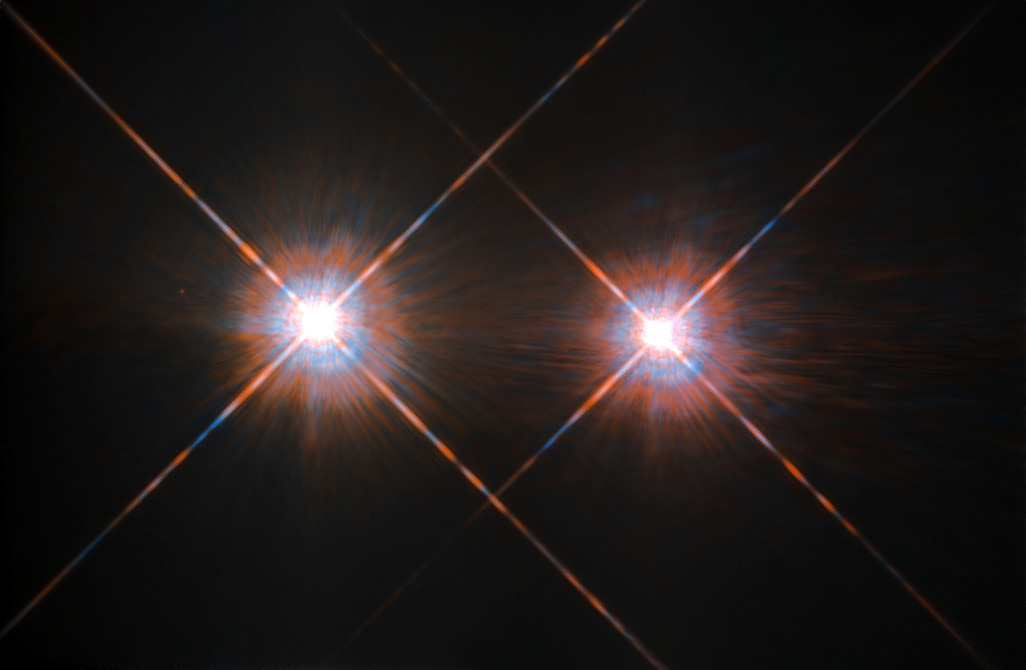

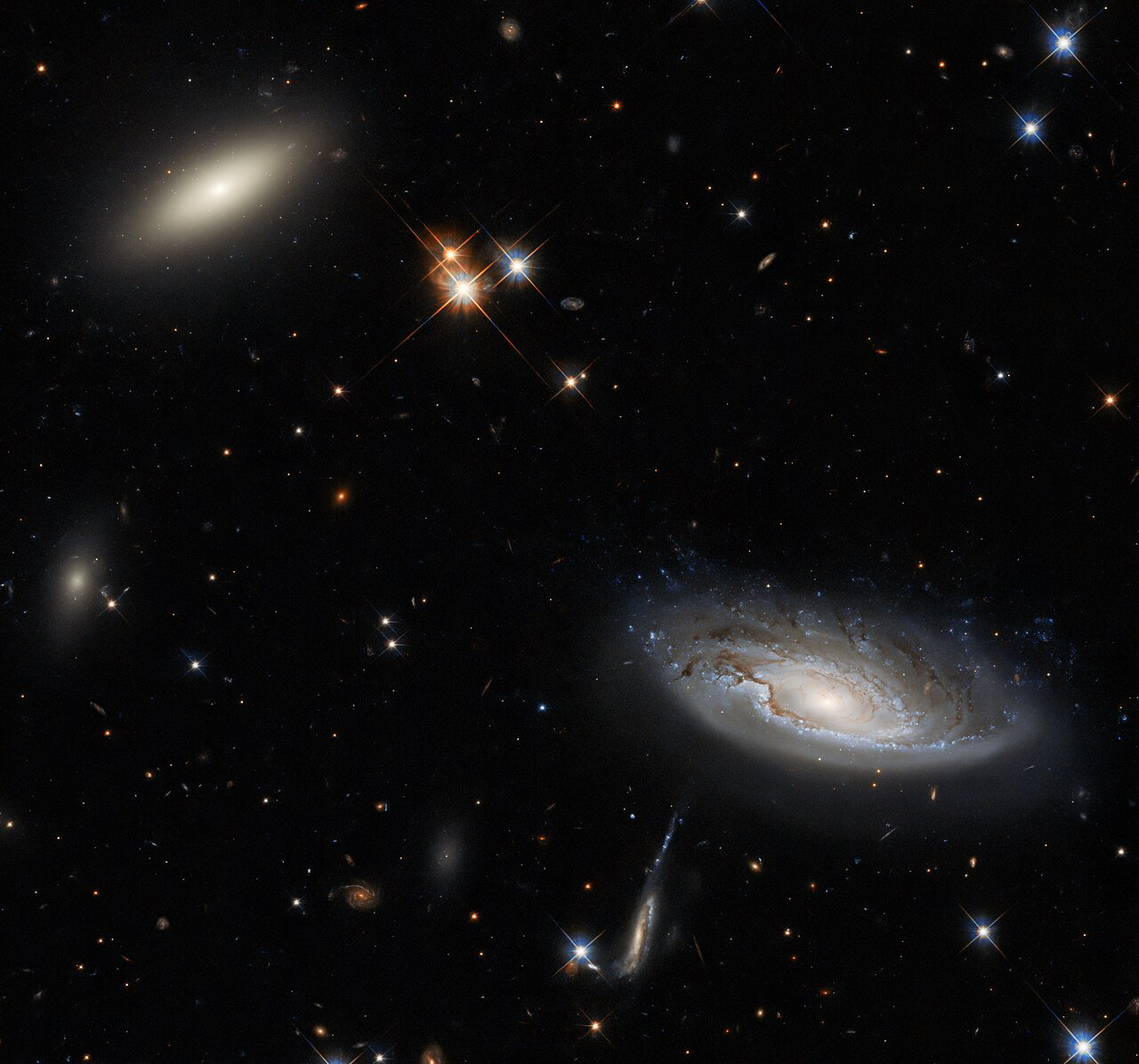

The closest star system to the Earth is the famous Alpha Centauri group. Located in the constellation of Centaurus (The Centaur), at a distance of 4.3 light-years, this system is made up of the binary formed by the stars Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B, plus the faint red dwarf Alpha Centauri C, also known as Proxima Centauri. The NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope has given us this stunning view of the bright Alpha Centauri A (on the left) and Alpha Centauri B (on the right), flashing like huge cosmic headlamps in the dark. The image was captured by the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2). WFPC2 was Hubble’s most used instrument for the first 13 years of the space telescope’s life, being replaced in 2009 by WFC3 during Servicing Mission 4. This portrait of Alpha Centauri was produced by observations carried out at optical and near-infrared wavelengths. Compared to the Sun, Alpha Centauri A is of the same stellar type G2, and slightly bigger, while Alpha Centauri B, a K1-type star, is slightly smaller. They orbit a common centre of gravity once every 80 years, with a minimum distance of about 11 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun. Because these two stars are, together with their sibling Proxima Centauri, the closest to Earth, they are among the best studied by astronomers. And they are also among the prime targets in the hunt for habitable exoplanets. Using the HARPS instrument astronomers already discovered a planet orbiting Alpha Centauri B. 24 August 2016 astronomers announced the discovery of an Earth-like planet in the habitable zone orbiting the star Proxima Centauri. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA

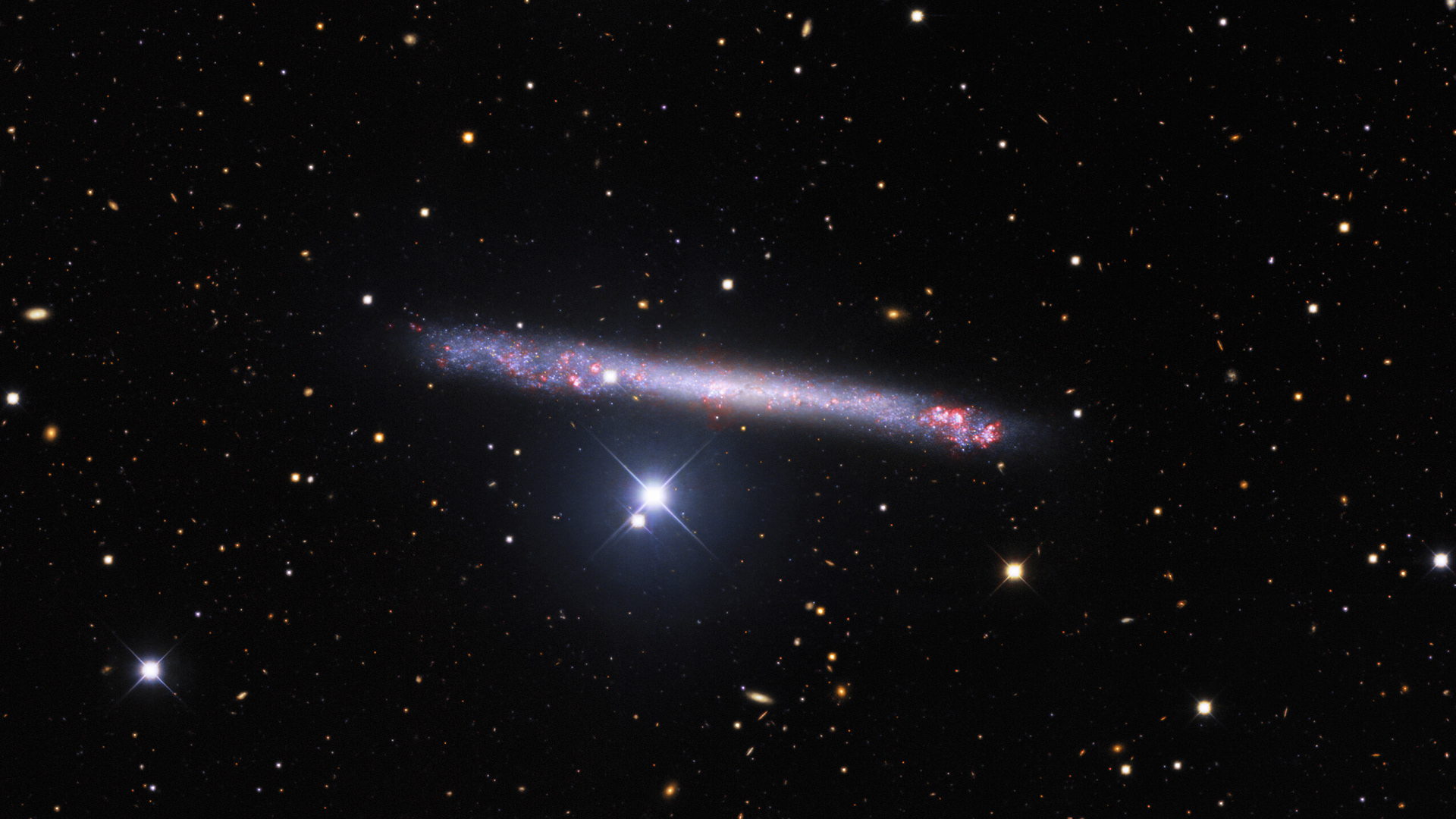

The Silver Sliver Galaxy — more formally known as NGC 891 — is shown in this striking image from the Mosaic instrument on the 4-meter Nicholas U. Mayall Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. NGC 891 is a spiral galaxy that lies almost perfectly edge-on to us, leading to its elongated appearance and its striking resemblance to our home galaxy, the Milky Way, as seen from the Earth. Since NGC 891 is oriented edge-on, it’s great for investigating the galactic fountain model. When stellar winds and supernovae from the disk of a galaxy eject gas into the surrounding medium, it can create condensation that rains back down onto the disk. The condensed gas then provides new fuel for star formation. In addition to the portrait of NGC 891, this image is littered with astronomical objects near and far — bright foreground stars from our own galaxy intrude upon the view of NGC 891 and distant galaxies lurk in the background. Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgements: PI: M T. Patterson (New Mexico State University) Image processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

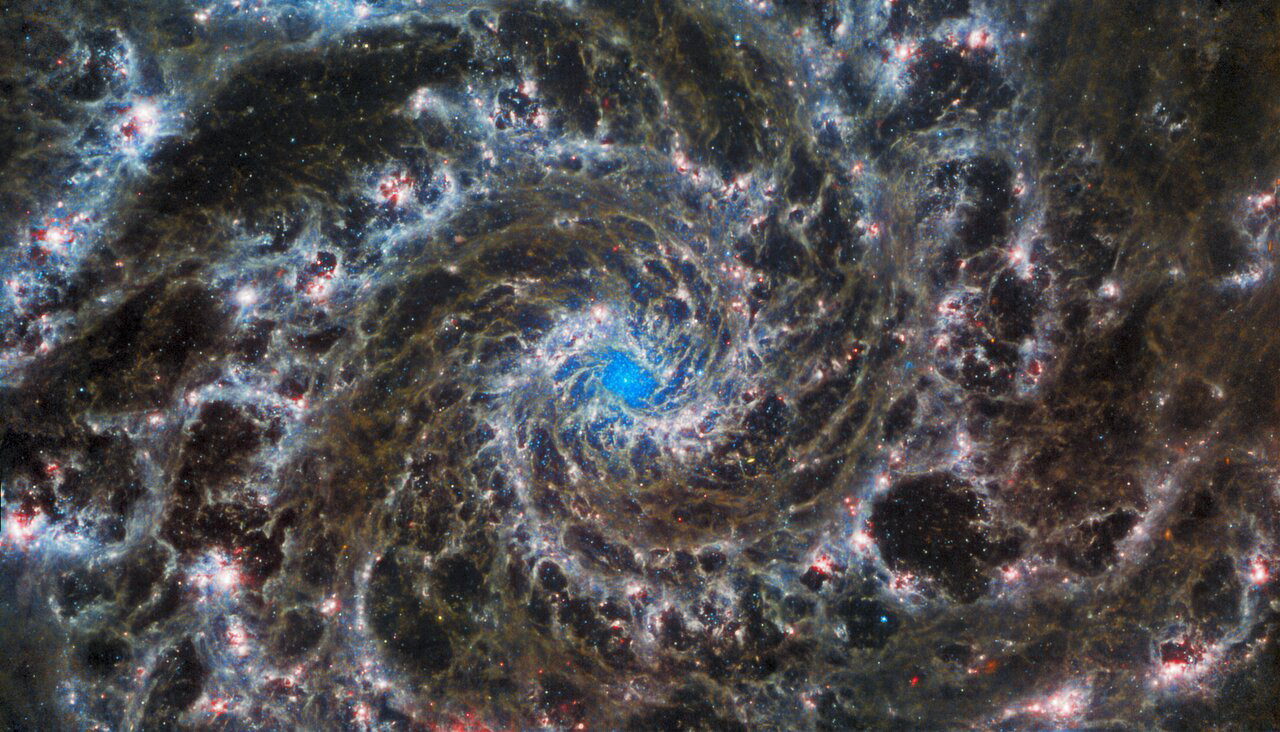

This image from the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope shows the heart of M74, otherwise known as the Phantom Galaxy. Webb’s sharp vision has revealed delicate filaments of gas and dust in the grandiose spiral arms which wind outwards from the centre of this image. A lack of gas in the nuclear region also provides an unobscured view of the nuclear star cluster at the galaxy's centre. M74 is a particular class of spiral galaxy known as a ‘grand design spiral’, meaning that its spiral arms are prominent and well-defined, unlike the patchy and ragged structure seen in some spiral galaxies. The Phantom Galaxy is around 32 million light-years away from Earth in the constellation Pisces, and lies almost face-on to Earth. This, coupled with its well-defined spiral arms, makes it a favourite target for astronomers studying the origin and structure of galactic spirals. Webb gazed into M74 with its Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI) in order to learn more about the earliest phases of star formation in the local Universe. These observations are part of a larger effort to chart 19 nearby star-forming galaxies in the infrared by the international PHANGS collaboration. Those galaxies have already been observed using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observatories. The addition of crystal-clear Webb observations at longer wavelengths will allow astronomers to pinpoint star-forming regions in the galaxies, accurately measure the masses and ages of star clusters, and gain insights into the nature of the small grains of dust drifting in interstellar space. Hubble observations of M74 have revealed particularly bright areas of star formation known as HII regions. Hubble’s sharp vision at ultraviolet and visible wavelengths complements Webb’s unparalleled sensitivity at infrared wavelengths, as do observations from ground-based radio telescopes such as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, ALMA. By combining data from telescopes operating across the electromagnetic spectrum, scientists can gain greater insight into astronomical objects than by using a single observatory — even one as powerful as Webb! MIRI was contributed by ESA and NASA, with the instrument designed and built by a consortium of nationally funded European Institutes (the MIRI European Consortium) in partnership with JPL and the University of Arizona. Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, J. Lee and the PHANGS-JWST Team. Acknowledgement: J. Schmidt

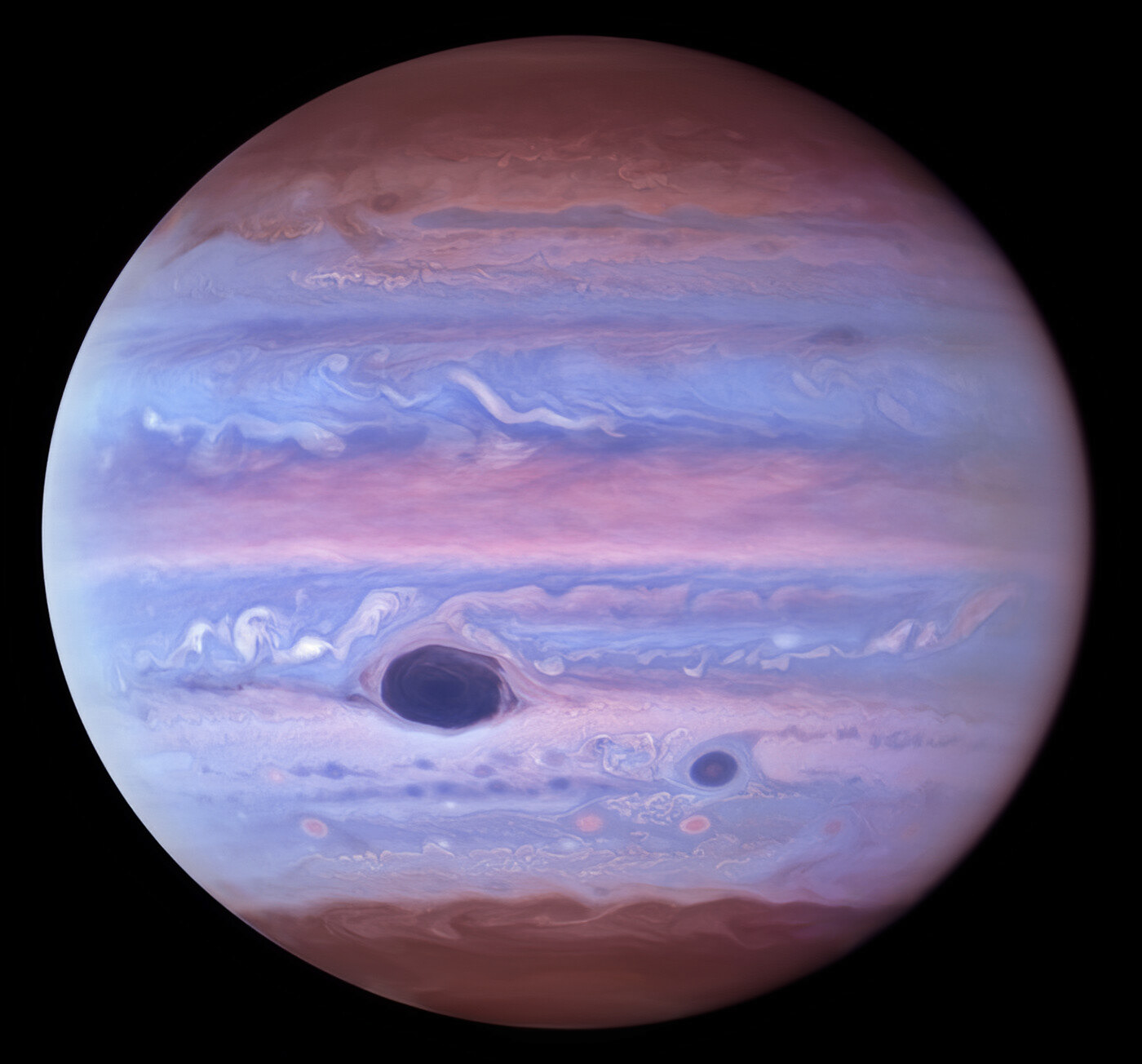

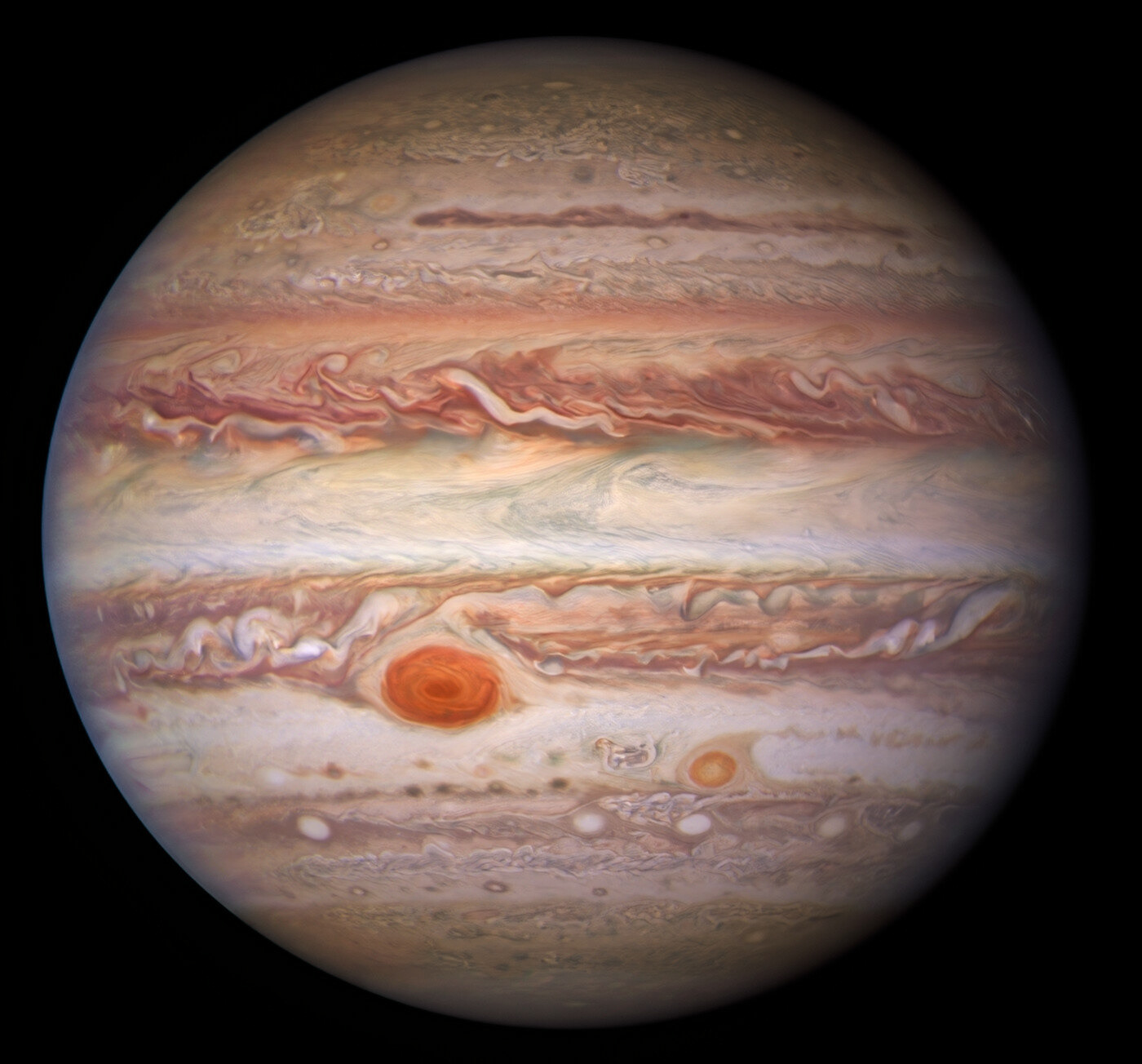

Three images of Jupiter show the gas giant in three different types of light — infrared, visible, and ultraviolet. The image on the left was taken in infrared by the Near-InfraRed Imager (NIRI) instrument at Gemini North in Hawaiʻi, the northern member of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. The center image was taken in visible light by the Wide Field Camera 3 on the Hubble Space Telescope. The image on the right was taken in ultraviolet light by Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3. All of the observations were taken on 11 January 2017. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/NASA/ESA, M.H. Wong and I. de Pater (UC Berkeley) et al

![The Dumbbell Nebula — also known as Messier 27 or NGC 6853 — is a typical planetary nebula and is located in the constellation Vulpecula (The Fox). The distance is rather uncertain, but is believed to be around 1,200 light-years. It was first described by the French astronomer and comet hunter Charles Messier who found it in 1764 and included it as no. 27 in his famous list of extended sky objects [2] .Despite its class, the Dumbbell Nebula has nothing to do with planets. It consists of very rarified gas that has been ejected from the hot central star (well visible on this photo), now in one of the last evolutionary stages. The gas atoms in the nebula are excited (heated) by the intense ultraviolet radiation from this star and emit strongly at specific wavelengths. This image is the beautiful by-product of a technical test of some FORS1 narrow-band optical interference filtres. They only allow light in a small wavelength range to pass and are used to isolate emissions from particular atoms and ions. In this three-colour composite, a short exposure was first made through a wide-band filtre registering blue light from the nebula. It was then combined with exposures through two interference filtres in the light of double-ionized oxygen atoms and atomic hydrogen. They were colour-coded as “blue”, “green” and “red”, respectively, and then combined to produce this picture that shows the structure of the nebula in “approximately true” colours. They are three-colour composite based on two interference ([OIII] at 501 nm and 6 nm FWHM — 5 min exposure time; H-alpha at 656 nm and 6 nm FWHM — 5 min) and one broadband (Bessell B at 429 nm and 88 nm FWHM; 30 sec) filtre images, obtained on September 28, 1998, during mediocre seeing conditions (0.8 arcsec). The CCD camera has 2048 x 2048 pixels, each covering 24 x 24 µm and the sky fields shown measure 6.8 x 6.8 arcminutes and 3.5 x 3.9 arcminutes, respectively. North is up; East is left. Credit: ESO/I. Appenzeller, W. Seifert, O. Stahl, M. Zamani](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

The Dumbbell Nebula — also known as Messier 27 or NGC 6853 — is a typical planetary nebula and is located in the constellation Vulpecula (The Fox). The distance is rather uncertain, but is believed to be around 1,200 light-years. It was first described by the French astronomer and comet hunter Charles Messier who found it in 1764 and included it as no. 27 in his famous list of extended sky objects [2] .Despite its class, the Dumbbell Nebula has nothing to do with planets. It consists of very rarified gas that has been ejected from the hot central star (well visible on this photo), now in one of the last evolutionary stages. The gas atoms in the nebula are excited (heated) by the intense ultraviolet radiation from this star and emit strongly at specific wavelengths. This image is the beautiful by-product of a technical test of some FORS1 narrow-band optical interference filtres. They only allow light in a small wavelength range to pass and are used to isolate emissions from particular atoms and ions. In this three-colour composite, a short exposure was first made through a wide-band filtre registering blue light from the nebula. It was then combined with exposures through two interference filtres in the light of double-ionized oxygen atoms and atomic hydrogen. They were colour-coded as “blue”, “green” and “red”, respectively, and then combined to produce this picture that shows the structure of the nebula in “approximately true” colours. They are three-colour composite based on two interference ([OIII] at 501 nm and 6 nm FWHM — 5 min exposure time; H-alpha at 656 nm and 6 nm FWHM — 5 min) and one broadband (Bessell B at 429 nm and 88 nm FWHM; 30 sec) filtre images, obtained on September 28, 1998, during mediocre seeing conditions (0.8 arcsec). The CCD camera has 2048 x 2048 pixels, each covering 24 x 24 µm and the sky fields shown measure 6.8 x 6.8 arcminutes and 3.5 x 3.9 arcminutes, respectively. North is up; East is left. Credit: ESO/I. Appenzeller, W. Seifert, O. Stahl, M. Zamani

Galaxy Galaxy, Burning Bright! / In the forests of the night lies a barred spiral galaxy called NGC 3583, imaged here by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. This is a barred spiral galaxy with two arms that twist out into the Universe. This galaxy is located 98 million light-years away from the Milky Way. Two supernovae exploded in this galaxy, one in 1975 and another, more recently, in 2015. There are a few different ways that supernova can form. In the case of these two supernovae, the explosions evolved from two independent binary star systems in which the stellar remnant of a Sun-like star, known as a white dwarf, was collecting material from its companion star. Feeding off of its partner, the white dwarf gorged on the material until it reached a maximum mass. At this point, the star collapsed inward before exploding outward in a brilliant supernova. Two of these events were spotted in NGC 3583, and though not visible in this picture of the week, we can still marvel at the galaxy’s fearful symmetry. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, A. Riess et al.

This is the first sunspot image taken on January 28, 2020 by the NSF’s Inouye Solar Telescope’s Wave Front Correction context viewer. The image reveals striking details of the sunspot’s structure as seen at the Sun’s surface. The sunspot is sculpted by a convergence of intense magnetic fields and hot gas boiling up from below. This image uses a warm palette of red and orange, but the context viewer took this sunspot image at the wavelength of 530 nanometers – in the greenish-yellow part of the visible spectrum. This is not the same naked eye sunspot group visible on the Sun in late November and early December 2020. Credit: NSO/NSF/AURA

This color-composite shows a main part of the new Blanco DECam Bulge Survey of 250 million stars in our galaxy’s bulge. The 4 x 2 degrees excerpt can be explored in all its whopping 50,000 x 25,000 pixels in this zoomable version. In the image interstellar dust and gas seemingly acts like a red “filter” in front of the background stars, scattering the blue light away. Since we are surrounded by dust and gas in the Milky Way, this scattering effect is important to many parts of astronomy and is known as interstellar reddening. DECam was primarily funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Acknowledgment: Image processing: W. Clarkson (UM-Dearborn), C. Johnson (STScI), and M. Rich (UCLA), Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin.

The spiral galaxy NGC 925 reveals cosmic pyrotechnics in its spiral arms where bursts of star formation are taking place in the red, glowing clouds scattered throughout it. Credit: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgements: PI: M T. Patterson (New Mexico State University) Image processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

The interaction of two doomed stars has created this spectacular ring adorned with bright clumps of gas — a diamond necklace of cosmic proportions. Fittingly known as the Necklace Nebula, this planetary nebula is located 15 000 light-years away from Earth in the small, dim constellation of Sagitta (The Arrow). The Necklace Nebula — which also goes by the less glamorous name of PN G054.2-03.4 — was produced by a pair of tightly orbiting Sun-like stars. Roughly 10 000 years ago, one of the aging stars expanded and engulfed its smaller companion, creating something astronomers call a “common envelope”. The smaller star continued to orbit inside its larger companion, increasing the bloated giant’s rotation rate until large parts of it spun outwards into space. This escaping ring of debris formed the Necklace Nebula, with particularly dense clumps of gas forming the bright “diamonds” around the ring. The pair of stars which created the Necklace Nebula remain so close together — separated by only a few million kilometres — that they appear as a single bright dot in the centre of this image. Despite their close encounter the stars are still furiously whirling around each other, completing an orbit in just over a day. The Necklace Nebula was featured in a previously released Hubble image, but now this new image has been created by applying advanced processing techniques, making for a new and improved view of this intriguing object. The composite image includes several exposures from Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, K. Noll

Centaurus A captured by the Dark Energy Camera - Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA Acknowledgments: PI: M. Soraisam (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign/NSF NOIRLab) Image processing: T.A. Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage/NSF NOIRLab), M. Zamani (NSF NOIRLab) & D. de Martin (NSF NOIRLab)

This striking image, streaked with bright swathes of color, captures the beautiful reflection nebula NGC 2170. The diffuse clouds of interstellar dust in the nebula scatter and reflect light from nearby stars, creating this vividly colorful scene. Dust grains reflect blue light from hot stars embedded in the nebula. And warm hydrogen gas glows a deep red. Seen as dark tendrils, dust also absorbs the light from stars and gas behind it. This particular nebula lies in the constellation Monoceros (The Unicorn) — a faint constellation on the celestial equator. It was observed using the SMARTS 0.9-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Credit: CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgments: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

Elliptical galaxies are generally characterized by their relatively smooth appearance when compared with spiral galaxies (one of which is to the left), which have more flocculent structures interwoven with dust lanes and spiral arms. NGC 474 is at a distance of about 100 million light-years in the constellation of Pisces. This image shows unusual structures around NGC 474 characterized as tidal tails and shell-like structures made up of hundreds of millions of stars. These features are due to recent mergers (within the last billion years) or close interactions with smaller infalling dwarf galaxies. This image is an excerpt from the Dark Energy Survey, which has released a massive, public collection of astronomical data and calibrated images from six years of work. The Dark Energy Survey is a global collaboration that includes the Department of Energy's (DOE) Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), and NSF’s NOIRLab. The image was taken with the Dark Energy Camera, fabricated by DOE, on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope. The quality of the survey can be appreciated by diving into the zoomable version of this wider excerpt showing a background tapestry of thousands of distant galaxies. Credit: DES/DOE/Fermilab/NCSA & CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgments: Image processing: DES, Jen Miller (Gemini Observatory/NSF's NOIRLab), Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin

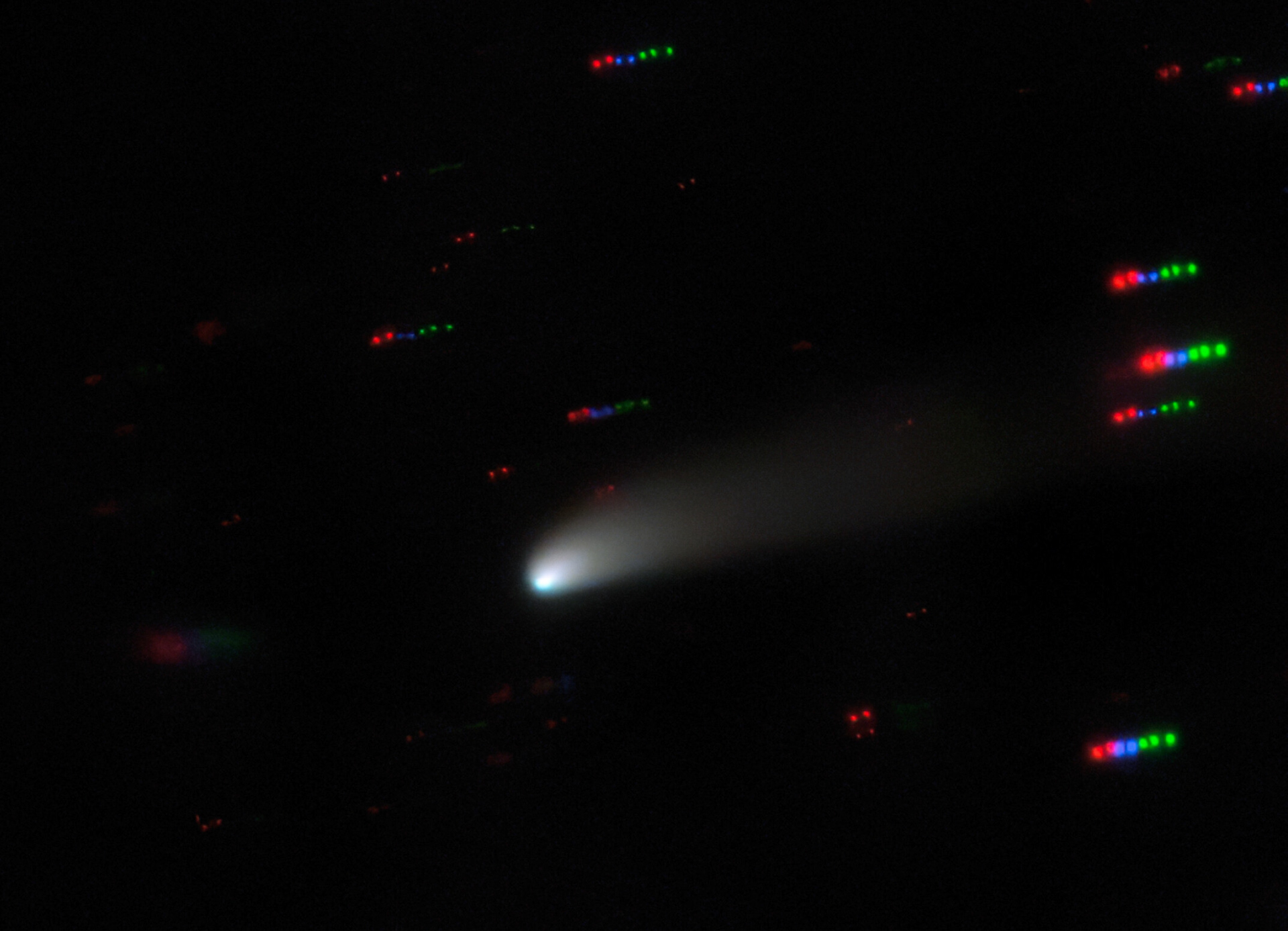

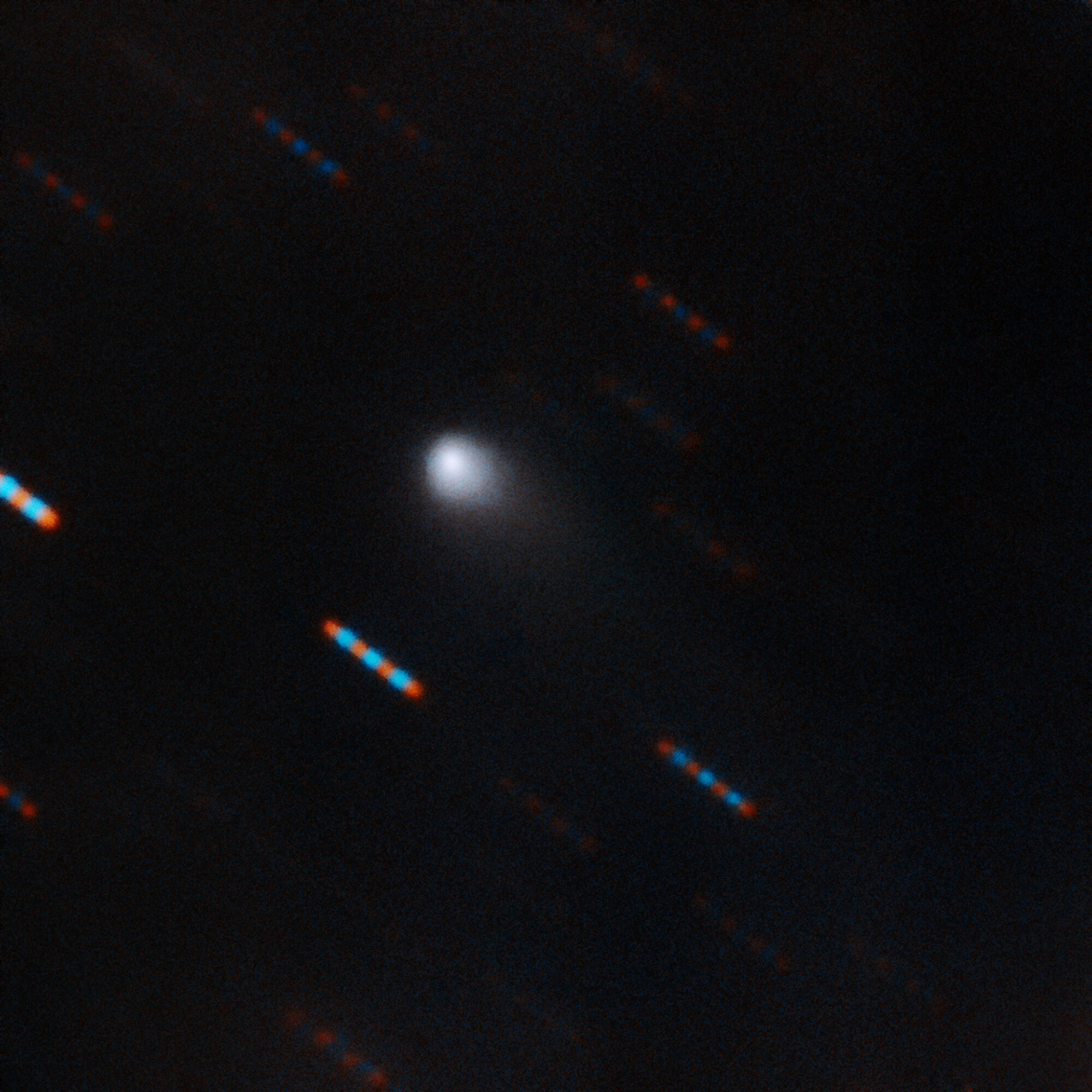

The blazing bright ball slicing through the center of this image is an example of a type of celestial body known as a centaur — a Solar System object that can be like both a comet and an asteroid. These fast moving icy objects reside in unstable orbits in the space between Jupiter and Neptune. The centaur in this image is named P/2019 LD2 (ATLAS), or LD2 for short. LD2 was observed from Gemini North, the Hawai‘i-based half of the international Gemini Observatory, which is a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. LD2 is on the cusp of an important transition — it is the first centaur to be seen in the process of changing into a comet-like state. It is slowly being nudged closer and closer towards the inner Solar System, which is causing its tail to form, and it is on track to move within Jupiter’s orbit in 2063. Once it does, it will cease to be a centaur, and will become a Jupiter Family Comet instead — joining a population of comets orbiting the Sun in less than 20 years and roughly in the same plane as most of the rest of the Solar System. That astronomers are able to witness LD2’s transition is unique and it is particularly exciting as many astronomers will be able to observe this metamorphosis within their own lifetimes — a fascinating glimpse of astronomy in action. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA Acknowledgments: PI: C.Schambeau (University of Central Florida) Image Processing: Travis Rector (University of Alaska Anchorage), Mahdi Zamani & Davide de Martin